[Updated February 23, 2016]

When parvo strikes, it moves fast. Infected dogs may appear to be in perfect health one day and violently ill the next. Emergency veterinary care is expensive, and unless dogs are diagnosed and treated early, many die from this serious disease.

However, reactions to parvovirus vary widely – both among dogs and their human caretakers. In a world in which parvovirus is ubiquitous – it is literally everywhere except environments that have been sterilized – parvo kills some dogs and leaves others unscathed. And in the debate about vaccination against this disease, some people vaccinate their dogs early and often, while others refuse to vaccinate against parvo at all.

In this article, we’ll discuss a number of parvovirus prevention and treatment approaches taken by veterinarians and dog guardians today. We’ll also share personal stories from two people whose dogs had parvovirus, and describe how these guardians’ experiences affected their healthcare strategies.

But we won’t tell you which approach you should take with your dog. That, like all health-related issues, is a personal decision that must be made after you learn as much as possible about the risks and benefits of the various approaches.

Understanding Parvo

The smallest and simplest of the microscopic infectious agents called viruses, which cause disease by replicating within living cells, parvovirus consists of a single strand of DNA enclosed in a microscopic capsid, or protein coat. This protein coat, which differs from the envelope of fat that encases other viruses, helps the parvovirus survive and adapt.

Parvoviruses infect birds and mammals (including humans), but until the 1960s, parvovirus did not infect domestic dogs or their wild cousins. The original canine parvovirus, later labeled CPV-1, was discovered in 1967. Eleven years later, CPV-2 emerged in the United States. It apparently mutated from feline distemper, which is the feline parvovirus. CPV-2 quickly infected dogs, wolves, coyotes, foxes, and other canines around the world. A second mutation, CPV-2a, was identified in 1979, and a third, CPV-2b, is in circulation today.

Infection takes place when a susceptible host inhales or ingests the virus, which attacks the first rapidly dividing group of cells it encounters. Typically, these cells are in the lymph nodes of the throat. Soon the virus spills into the bloodstream, through which it travels to bone marrow and intestinal cells. The incubation period between exposure and the manifestation of symptoms such as vomiting and diarrhea is usually three to seven days.

When it attacks bone marrow, parvo damages the immune system and destroys white blood cells. More commonly, it attacks the intestines, causing copious diarrhea and debilitating nausea, which further weakens the dog’s system. Dogs who die of parvo typically do so because fluid loss and dehydration lead to shock, and/or because intestinal bacteria invade the rest of the body and release septic toxins.

Any dog that survives a parvovirus infection is believed to have lifelong immunity; serum antibody titers tend to stay high for prolonged periods after recovery from the virus.

Young puppies and adolescent dogs whose maternal antibodies no longer protect them but whose immune systems have not yet matured are at greatest risk of contracting parvo. Most parvo victims are less than one year old, but the disease can and does occasionally strike adults, too.

Some breeds are particularly susceptible to contracting parvovirus, including Alaskan Sled Dogs, Doberman Pinschers, German Shepherd Dogs, Labrador Retrievers, Rottweilers, and American Staffordshire Terriers.

How Parvo Spreads

Veterinary experts agree that virtually all of the world’s dogs have been exposed to canine parvovirus. The virus begins to “shed,” or be excreted by a dog, three to four days following his exposure to the virus, often before clinical signs of the infection have appeared. The virus is also shed in huge amounts from infected dogs in their feces for 7-10 days; a single ounce of fecal matter from a parvo-infected dog contains 35,000,000 units of the virus, and only 1,000 are needed to cause infection.

In addition, the virus can be carried on shoes, tires, people, animals (including insects and rodents), and many mobile surfaces, including wind and water. Because it is difficult to remove from the environment and because infected dogs shed the virus in such profusion, parvo has spread not only to every dog show, veterinary clinic, grooming salon, and obedience school, but every street, park, house, school, shopping mall, airplane, bus, and office in the world.

While a dog that is diagnosed with parvo will be quickly isolated by his veterinarian and his recent environment will be cleaned and disinfected, some infected dogs have such minor symptoms that no one realizes they are ill. Infected dogs, with or without symptoms, shed the virus for about two weeks. If conditions are right, the virus can survive for up to six months. Although parvo is destroyed by sunlight, steam, diluted chlorine bleach, and other disinfectants, sterile environments can be quickly reinfected.

Medical Treatment

Most veterinarians treat parvovirus with intravenous fluids and antibiotics. In addition, treatment may include balancing the blood sugar, intravenous electrolytes, intravenous nourishment, and an antiemetic injection to reduce nausea and vomiting. None of these treatments “cure” the disease or kill the virus; they are supportive therapies that help stabilize the dog long enough for his immune system to begin counteracting the virus.

According to Los Angeles veterinarian Wendy C. Brooks, DVM, “Every day that goes by allows the dog to produce more antibodies, which bind with and inactivate the virus. Survival becomes a race between the damaged immune system, which is trying to recover and respond, and potentially fatal fluid loss and bacterial invasion.” Puppies and very small dogs are at greatest risk because they have the smallest body mass and can least afford to lose vital fluids.

Bill Eskew, DVM, sees more parvo patients than many veterinarians because he specializes in emergency care. A veterinarian for 25 years, Dr. Eskew currently works in busy clinics in California and Florida. He says fluids and electrolyte balance are the most important aspects of parvo treatment.

“My typical parvo patient is a four-month-old unvaccinated or partially vaccinated puppy,” says Dr. Eskew, “and I see as many as 20 a week. I’m convinced that of all the treatments we use, intravenous fluids make the most difference. In one case I treated a litter of puppies for a man who couldn’t afford antibiotics or other drugs, so I used fluids alone, and the pups all recovered. In fact, as far as I know, all my parvo patients have survived.”

While antibiotics have no effect on viruses, they are considered an important aspect of treatment, especially for puppies. The parvovirus causes the gastrointestinal mucosa, which usually serves as a protective barrier to infection, to slough away, leaving the puppy vulnerable to bacterial infections. Antibiotics protect the puppy from infection until his body’s own system of protection recovers.

CPV Recovery Rates

According to Dr. Brooks, an estimated 80 percent of parvo-infected dogs treated at veterinary clinics recover.

Dr. Eskew credits his success rate to early diagnosis. “The minute we see a puppy that’s been vomiting or has diarrhea,” he says, “we give it a parvo test. The one we use is a rectal swab that shows results within 10 minutes.”

Of course, such early detection tools can be used only if the dog’s guardian is alert to the early signs of illness and hustles him to the veterinary clinic as soon as possible. The sooner the dog receives supportive care, the better his odds of recovery.

Vaccines: Imperfect Protection

Properly administered, vaccines protect most puppies and dogs from parvovirus. But there are cases of vaccinated canines contracting the disease.

In late 1998, WDJ received a letter from a reader whose nine-month-old puppy had contracted (and, happily, recovered from) parvovirus. She was perplexed as to how her properly vaccinated puppy could have become infected, especially since she also owned a brother from the same litter who did not become sick, even though both pups had received the same vaccinations and had been exposed to the same things and places!

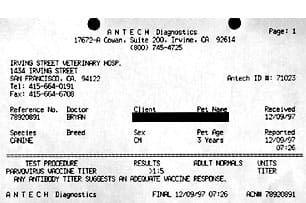

The experience of the letter writer’s next-door neighbor added to the mystery. After hearing about the puppy with parvo, the neighbor took her six-month-old, vaccinated puppy to the veterinarian for titer tests, to make sure this puppy was protected. The test indicated that the puppy had no immunity to parvovirus, so she had the pup revaccinated immediately.

For explanations for all these puzzling events, we turned to Jean Dodds, DVM, an expert in veterinary hematology and immunology. Dr. Dodds is also founder and president of Hemopet/Pet Life-Line, of Garden Grove, California. Hemopet is a national nonprofit animal blood bank and adoption program for retired Greyhounds.

Dr. Dodds offered numerous explanations as to why, sometimes, the parvovirus vaccine fails to work as intended.

First, she made clear, no vaccine produces 100 percent protection 100 percent of the time. “Vaccination is not a sure thing,” she explained. “It certainly improves the odds that an animal will be protected from disease, but it does not guarantee this. There is no way, even with the best vaccines, to be sure that any given individual’s immune system will respond in the desired way to protect that animal.”

Not all dogs have perfectly functioning immune responses, and, similarly, not all vaccines function perfectly, either. “There will always be an occasional case of a ‘vaccine break,’ which is what we call it when a vaccine fails to protect an individual against an infectious disease challenge,” said Dodds. “However, when a break occurs, if the animal has been appropriately vaccinated, it will usually experience only a mild form of the disease.” Dr. Dodds speculated that this is the most probable explanation for what happened with the infected puppy mentioned above.

“While there are some rare exceptions, where an appropriately vaccinated animal nonetheless experiences a lethal form of the disease, it is far more typical that such an animal will experience only a mild form of the disease and will recover quickly,” she said.

However, the most common reason for vaccine failures in puppies is maternal antibody interference. Dr. Dodds explained that if a puppy receives a particularly high level of antibodies (passive immunity) from his mother’s colostrum (and to a lesser extent, in utero), these maternal antibodies may cause any vaccine antigens that are administered to be neutralized. Then, when these antibodies wane (usually between 6 and 16 weeks of age), the puppy is left without adequate protection, and has not become actively immunized.

“Maternal antibodies wane at an unpredictable rate, which is why puppies are vaccinated several times at intervals of two to four weeks apart,” said Dr. Dodds. “This is designed in an effort to cover any potential gap in protection or ‘window of susceptibility’ that arises from the waning of maternal passive immunity and the onset of active immunization and protection by vaccination.”

Because of this, a test for serum antibody titer or an additional vaccination is sometimes recommended at 15-16 weeks, especially in high-risk breeds.

Trouble with Titers

Regarding the neighbor’s vaccinated puppy, whose antibody titers showed no antibody protection for parvo: Dr. Dodds thinks that the chances are very good that the puppy actually did have adequate protection from parvovirus, despite the misleading titer test results.

“There are two types of titer tests commonly offered by most veterinary medical laboratories,” Dr. Dodds explained. “One type is intended to detect whether or not a dog has the disease (a viral infection); the other type of titer test checks the level of immunity the dog received from vaccination. In the latter case (a vaccine titer test), antibody levels are expected to be several titer dilutions lower than those conveyed by active viral infection.

“When a veterinarian requests an immunity or antibody level measurement for parvovirus or other disease, the laboratory typically assumes that disease diagnosis, rather than vaccine immunity, is to be performed. When the lab technicians do a test to see whether the dog has parvovirus, they start with a much greater dilution in the test system than is normally used for the detection of vaccine titers. They do this to conserve reagent and reduce cost of testing. But because vaccine titers are lower than disease titers, they won’t be detected until the test reagent dilution is set lower.

“I’ll put it a different way: If they utilize disease exposure methodology, when what is really wanted is a test to assess the adequacy of vaccination, the results will be negative nearly every time,” said Dodds.

While this scenario sounds like an obvious oversight, Dr. Dodds said she has seen it numerous times. Given her expertise and research on vaccine-related issues, many veterinarians consult with Dr. Dodds regarding supposed vaccination failures.

“I’ve seen it again and again: The owner calls me and says, ‘But I keep vaccinating this animal, and my veterinarian keeps testing him and there is no immunity; what do I do?!’

“Very often,” said Dr. Dodds, “it’s a case where the veterinarian looked at the lab catalog and selected the test called ‘Parvovirus Antibody’ rather than the intended one, which would be ‘Parvovirus Vaccine Antibody’ or ‘Parvovirus Vaccine Titer.’ Meanwhile, the poor animal has been vaccinated repeatedly and unnecessarily, and when we finally get the correct measurement, we find that the animal actually had good immunity all along.”

Not Necessarily Parvo

Back to the puppy who was vaccinated but was stricken with parvo anyway: A final explanation is that his illness might have been incorrectly diagnosed. Dr. Dodds explained that veterinarians diagnose parvo by its symptoms – fever, depression, diarrhea, vomiting – and by checking the dog’s stool for presence of parvovirus or serum antibody level. But other gastrointestinal diseases can produce symptoms that closely resemble those of parvo. And even the presence of low levels of parvovirus in the stool doesn’t necessarily mean that the dog’s symptoms are caused by it.

“Dogs who are vaccinated and fully protected against parvovirus may still shed the virus in their stool if they are exposed to the disease agent,” said Dr. Dodds. “Unless the stool sample revealed a moderate to heavy parvovirus infection, I would suspect that the dog’s symptoms could be caused by something else, or a combination of parvovirus exposure and another infectious agent. For example, the puppy could have been exposed to both parvovirus and corona virus, and then suffered diarrhea and other symptoms as a result of the corona virus alone, because he was adequately protected by vaccination against parvovirus.”

Preventive Measures for Unvaccinated Dogs

Can a superior diet protect unvaccinated dogs against parvo? When parvovirus first infected the world’s dogs, thousands credited Juliette de Bairacli Levy’s Herbal Handbook for the Dog and Cat and its Natural Rearing philosophy for saving their dogs’ lives. Levy was the first to advocate a well-balanced raw, natural diet for pets.

Marina Zacharias raised four Basset Hound pups on the Natural Rearing diet. When they were six months old, they played with a puppy the day before it was diagnosed with parvo. “For 10 days after exposure, I gave them one of Juliette’s disinfecting herbal formulas plus homeopathic remedies to help boost their immune function,” she says. “On the tenth day, one of my pups started to show symptoms so I treated it with castor oil to help sweep away the virus as Juliette describes in her book, and I continued with homeopathics. Within two hours this pup was completely back to normal. The other three never showed symptoms and remained healthy.”

Zacharias has received similar reports from numerous clients whose raw-fed, unvaccinated puppies were exposed to parvo. Homeopathic nosodes, which are highly diluted remedies made from the disease material of infected animals, have become popular alternatives to conventional vaccines. But many veterinary homeopaths believe their use as surrogate vaccines is inappropriate.

One is Maryland veterinarian Christina Chambreau, who explains, “The best time to use a homeopathic nosode is after exposure. If you know your dog has been exposed to parvo, you would give a single dose of a 200C-strength homeopathic parvo nosode. This treatment can be given any time after exposure and before the animal gets really sick, such as when it shows minor symptoms like throwing up once or having soft stools.”

Dr. Chambreau says she is aware of about 50 cases in which unvaccinated or minimally vaccinated litters of puppies, kennels of dogs, or individual dogs were exposed to parvo, and after a single treatment with the parvovirus nosode, either did not get the disease at all or had only minor symptoms.

Dr. Chambreau also recommends feeding the best possible diet and boosting the dog’s immune system with supplements such as vitamin C and infection-fighting herbs like echinacea. It is not uncommon, she says, for holistically raised, unvaccinated puppies to have parvo without being diagnosed.

“Many of my clients choose not to vaccinate at all,” Chambreau says, “and it’s not uncommon for their puppies to get sick with a mild case of diarrhea or vomiting that we treat homeopathically or with other holistic therapies. These puppies recover quickly, and what’s interesting is that later, when they’re directly exposed to parvo, they don’t catch it. That minor bout of diarrhea was probably parvo. It’s possible to raise puppies so that they get a natural exposure rather than a vaccine exposure to parvo, and that builds a better immunity than the vaccine in most animals.”

California veterinarian Gloria Dodd first dealt with parvovirus when it appeared 20 years ago. “When parvo first mutated from the Feline Distemper virus, it hit the canine world hard,” she says. “Here was an entire population with no immunity to this new viral infection. In a single week, I was overwhelmed with 55 dogs that had severe clinical infection with bloody diarrhea, vomiting, dehydration, and shock.” The virus affected dogs of all ages, from puppies to 15-year-old dogs with congestive heart failure and others with liver and kidney disease.

“To treat this new illness,” she says, “I made an autoisode. An autoisode is a homeopathic remedy made from the secretions, excretions (saliva, urine, or feces), blood, and hair of the infected animal, for these substances contain the infective agent. I used them to make a sterile intravenous injection and gave this to all of the animals. I didn’t lose a single patient.”

The 30C potency parvovirus autoisode that she made during the epidemic has become the basis of her homeopathic parvo prevention, and she is not aware of any animals, either her own or her clients’, breaking with parvo. “On the contrary,” she says, “it has proven to be protective for unrelated infections by building and strengthening the dog’s own immune system to ward off other infective agents. When I gave it to a Connecticut kennel of Boston Terrier show dogs, they were the only dogs that did not contract kennel cough during an outbreak at a dog show in Massachusetts.”

Weighing the Risks

We want our dogs be healthy and to live forever. Conventional veterinarians see parvo-virus as an easily prevented, unnecessary illness, and vaccination as a simple, inexpensive component of basic care. Many holistic vets take a different view. Both sides make compelling arguments.

“These are difficult decisions,” says Dr. Chambreau. “Which is more devastating: To have an animal die at any age from an acute disease? Or to protect it from the acute disease and watch it develop chronic skin problems, allergies, or autoimmune disorders before it dies of cancer? There are no easy answers.”

VERY GOOD INFORMATION. THANK YOU.