This excerpt is the first chapter of Dog Smart, a new book by Linda Case, MS, founder and head trainer at AutumnGold Dog Training Center in Mahomet, Illinois, and the author of a number of books on training and animal nutrition. Case also taught at the University of Illinois Department of Animal Sciences and College of Veterinary Medicine for 20 years.

To purchase Dog Smart or any other of Case’s books, click here.

Just recently, during my school’s beginner class orientation, a new student asked this:

“My neighbor Joe (who knows a lot about dogs), told me that because wolves are the ancestors of dogs, we should train dogs according to how wolves behave in packs. He told me that I need to be ‘alpha’ and that my dog must recognize my dominant status during training. Will we be making sure that my dog Muffin (a Mini-Doodle) knows that I am dominant?”

And I think, “Here we go again.”

The problem with this rationale – the dog’s primary wild ancestor is the wolf; therefore we should base our training practices on what is known about wolf behavior – is that, like many folklores, it contains elements of truth plus a slew of falsehoods and mythologies.

How do you answer in one minute or less to a skeptical student, friend, or neighbor (Joe)?

The best way is to arm yourself with facts and then condense those facts into a short and easily understandable response. In this chapter, we review current knowledge regarding the dog’s ancestry, domestication and basic social behavior. Then, I will provide you with a few “Talking to Joe” responses that you can use in your classes, when teaching seminars, talking to other dog owners, and, of course, when attempting to convince neighbor Joe (who may need a lot of convincing).

© Lochstampfer | Dreamstime.com

It’s All Greek (er, Latin) to Me

Let’s start with the dog’s taxonomy, which is the hierarchical system that we use to classify animals. Although this information may seem somewhat academic, it is important for trainers to know the dog’s taxonomy because it allows us to see just how closely related the dog is to the wolf and other canid species. The broadest classification groups are domain and kingdom, followed by the increasingly narrow groups of phylum, class, order, family, genus, and species. The genus and species Latin names are how we typically identify animals, including the dog.

The domestic dog is classified within the “phylum” Animalia, the “class” Mammalia, and the “order” Carnivora. Carnivora includes 17 families and about 250 different species.

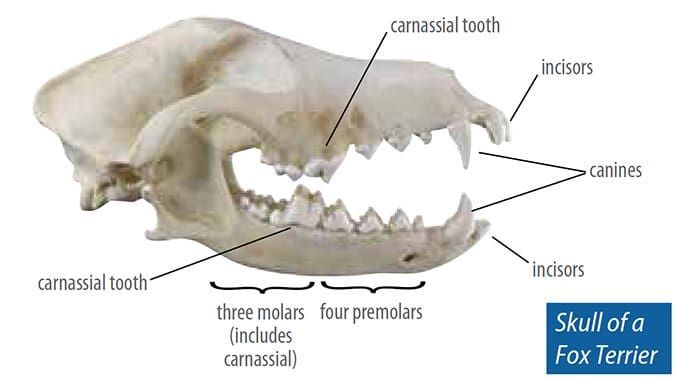

Carnivores are so named because of a set of enlarged teeth (the carnassials) that comprise the enlarged upper fourth premolar and the lower first molar on each side of the mouth. Take a moment to open your dog’s mouth and take a look at those teeth. If you live with anything larger than a Chihuahua, you will notice that these are some mighty big chompers.

If you brush your dog’s teeth regularly, you are already familiar with the carnassials because they present the flattest and largest tooth surface that you run your brush across – and are also a popular spot for plaque and calculus to deposit. All of the species that are classified with dogs in this order have these impressive teeth, which are adapted for shearing and tearing prey.

Carnivores also have small, sharp incisors at the front of the mouth for holding and dissecting prey. These are the teeth that Muffin uses to de-fluff her new stuffed squeaky toy.

The four elongated canine teeth evolved for both predation and defense.

Interestingly, despite these dental modifications, not all of the present-day species that are found in Carnivora are strict carnivores. Some, such as bears and raccoons, are omnivorous and at least one species, the panda, is primarily vegetarian.

“Families” are groups within the orders, with dogs found in the family Canidae and in the “genus” Canis. Other canids within the Canidae family are wolves (two species), coyotes (one species), and foxes (five species).

The wolf and the dog hang together taxonomically all the way down through genus and only separate when classified as separate species; wolves are Canis lupus and dogs are Canis familiaris. (Note: There is still a bit of disagreement about this among scientists. Some argue that dogs should be classified as a sub-species of wolf: Canis lupus familiaris. There is no consensus about this and you may see dogs classified both ways.)

Cousin, Not Ancestor

Cousin, Not Ancestor

So, this is where you can start with your answer to Joe: Dogs and present-day wolves are different species within the same genus. The Latin name for the domestic dog is Canis familiaris and the present-day Gray wolf is Canis lupus.

To which, Joe replies: “Yeah, but the wolf is the dog’s ancestor, right?” This is one of those pesky partial truths. The domestic dog and today’s Gray wolf share a common ancestor, a type of wolf that lived at least 45,000 years ago and has since gone extinct. Much in the same way that the chimpanzee (Pan troglodytes) is the closest living relative to present-day humans (Homo sapiens), we do not (and should not) refer to the chimpanzee as our ancestor. This is incorrect. Just as we share a common ancestor with present-day great apes, dogs share a common ancestor with today’s wolves.

Man’s Oldest Best Friend

However closely dogs may be related to wolves from an evolutionary perspective, they are different in many important ways. The first distinction is that dogs, unlike wolves, are a domesticated species. They are in fact, the first animal that humans domesticated. We were hanging out with dogs several thousand years before we began tending to chickens, goats, pigs, or cows, and even well before cats were living with us (who, by the way, maintain that this arrangement was entirely their decision, not ours).

Scientists still do not concur about the exact timing, place, or circumstances surrounding the creation of dog, but there are several general facts with which most currently agree:

- Domestication, the process by which the ancestral wolf was gradually transformed into the dog, took place sometime between 32,000 and 18,000 years ago.

- The most recent evidence suggests that the dog was domesticated more than once, from two different and geographically separated (now extinct) wolf populations that were living on opposite sides of the Eurasian continent. Over time, these two groups of proto-dogs migrated with humans and intermingled.

- Domestication began during a time when people were still living a nomadic lifestyle, periodically moving their camps from place to place. Our more settled way of life did not become established until 12,000 years ago with the invention of agriculture.

- The early stages of domestication of the dog appear to have been unintentional. As wild wolves identified a new ecological niche – the food scraps and garbage that were associated with human campsites – they began to follow human camps and to live on the periphery of temporary settlements to scavenge food.

- The selective pressures on these camp-dwelling wolves favored less timid individuals who had a higher tolerance of humans. Less fearful individuals would experience increased opportunities to feed and reproduce because they stayed longer and fled less readily than more timid animals. These new sub-populations of wolves were also feeding themselves more through scavenging and less through hunting (predation).

- Over generations, selective pressures led to a proto-dog who was naturally tolerant of human presence and began to live permanently near human camps and settlements. This evolving dog was smaller, had a shorter snout, wider skull, and smaller teeth compared with wolves.

Pack Behavior?

Changes also occurred in the wolf’s social behavior during domestication. As early dogs began to live permanently as camp scavengers, the selective pressure for social hierarchies and strict pack order was relaxed as pack hunting behaviors were no longer needed and were replaced by semi-solitary or group scavenging behaviors. Scavengers became more tolerant of the presence of other dogs and the presence of protected nesting sites also reduced the need for cooperative raising of young.

It is theorized that during this branching of the dog and wolf’s evolutionary tree, the wild version of wolf remained a pack-living predator, while the evolving dog became specialized in adaptations for living in close proximity to humans. Dogs also evolved a set of social behaviors that enhanced their ability to communicate and cooperate with human caretakers. It is from these semi-domestic scavenger populations that individual dogs are believed to have been selected and purposefully bred by humans for further taming. Eventually (many generations later), selective breeding of these dogs led to the development of different types of working dogs and, most recently, the creation of purebred breeds.

Origins of the Dominance Myth

Given this current understanding of the dog’s domestication, why is it that Joe and his friends continue to believe that pack order and dominance hierarchies are so important to dogs and should be used in dog training? For this explanation, we have to look more to recent history, going back only about 45 years.

During the 1970s, researchers who were studying wolf behavior focused almost exclusively on a theory called the “hierarchal model of pack behavior.” This theory proposes that individuals within a wolf pack are highly concerned with social status and live in a constant struggle for dominance with one another. Because of the dog’s close evolutionary relationship to the wolf, it was assumed that dogs would behave similarly.

It became popular to view dogs as pack-living animals who adhered to strictly structured dominance hierarchies – both with their human owners and with other dogs.

As a result of this highly popularized (but incorrect) concept, almost any behavior that a dog offered that was not in compliance with an owner’s wishes came to earn the label of “dominance.” An entire collection of dog training methods grew out of these beliefs, most of which focused on ensuring that that owners established dominant (also referred to as “alpha”) status over their dogs. These methods emphasized physical coercion and punishment, and promoted exercises that were believed to be necessary for effectively establishing the owner’s dominant status.

Interesting Theory…

Too bad this concept is wrong. There are several errors with this way of thinking. The first lies in the set of false beliefs about wolf behavior that prevailed in the 1970s. Wolf researchers have since reevaluated the appropriateness of using the hierarchy model of social behavior and have found it to be lacking.

Despite the widespread belief that wild wolf packs exist in a perpetual state of dominance challenges and bids for enhanced status, the collected evidence shows a glaring absence of these rigid types of relationships. There are few reports of wolves seeking higher positions in their pack, fighting over leadership, or physically dominating other wolves through aggression or alpha rolls.

Rather, today’s wolf experts tell us that the social behavior of wild wolves typically reflect cohesive, well-functioning family units that are built around cooperation rather than conflict. Pack peace is maintained not through aggression and perpetual battling for dominance, but rather through ritualized postures designed to avoid fights and cooperative behaviors such as hunting together, sharing food and raising young together. A parent-family model better describes wolf relationships in packs than does an outdated hierarchy model that focuses on strict social roles and conflict.

This doesn’t mean that wolves never display social dominance, however, or that the concepts of dominance and submission are completely useless as descriptors of behavior. Wolves (and other animals, including dogs and humans) display social dominance situationally, most often when attempting to defend a valuable resource. It is not the entire concept of dominance and dominant/submissive signaling that has been dispelled, but rather the correctness of a simple hierarchical pack structure. That concept is considered obsolete and inaccurate today.

Additionally, our understanding of both learning theory and the cognitive ability of dogs has evolved significantly over the years. Attempting to use a simple dominance hierarchy model to explain all things wolf (and dog) has fallen short when considering new evidence that supports the existence of complex thought, planning, perspective taking, and even rudimentary elements of a “theory of mind” in animals, including wolves and dogs.

And finally, we know much more about the social behavior of dogs than we did back in the 1970s. To put it bluntly: Dogs are not wolves. They do not form packs like wolves (not even at the dog park – sorry, Joe, wrong again), nor do they possess a natural tendency to battle for dominance or a need to constantly challenge humans or other dogs for higher status. Their social lives and relationships are also, just like wolves and other animals, much more complex than a simple concept of dominance hierarchy is capable of describing fully.

For example, one of the most striking ways in which dogs differ from wolves is in the dog’s ability to understand and learn from human communication signals.

The reality is that the social behavior and cognition of the dog has been profoundly influenced by domestication. Today’s dog is described by some as a socialized wolf, a variant who is well-adapted to life with humans and has lost the need to exist in a stable (wolf) pack.

In groups, feral dogs do not typically hunt cooperatively and only rarely share care of offspring. In homes, the domestic dog’s social behavior is directed more toward working with and communicating with humans, not competing with us for some arcane concept of dominance. Similarly, the relationships that dogs share with other dogs in their homes are not analogous to a wolf pack. Rather dogs have social partners (friends really) and acquaintances, just like humans. Importantly, the social groups of dogs, with humans and with other dogs, have characteristics and structures that are adaptive for domestication and for living in close proximity with their human caretakers. These characteristics are all uniquely and amazingly dog (not wolf).

Talking to Joe

So, how do we distill this down to facts that will convince Joe that his dog (a) is not a wolf and (b) does not require dominating? Here are a few talking points that you can modify as needed for your particular Joe.

- Yes, Joe, dogs and wolves are closely related. However, today’s wolf is not actually your dog’s ancestor. Rather dogs and wolves are cousins, similar in many ways to the relationship between you and a chimpanzee, Joe. Just as you would not look at chimpanzee behavior to inform you how to raise your kids (at least I don’t think you would), you should avoid focusing on wolf behavior to tell you how to raise and train your dog.

- Dogs differ from wolves in some amazing ways. They are more attuned to our facial expressions and communication signals, and they are better at cooperating with humans than are wolves. Dogs also often form friendships with other dogs in their home or community, and despite the continued attempts by some to describe it in this manner, dogs do not live in a constant state of dominance-dictated competition with other dogs.

- So, time to chill, Joe. Don’t worry so much about your dog’s status in your home or whether or not he is attempting to dominate you, your family and the world. (He’s not.) Rather, focus on all of the amazing traits and talents that your dog has inherited as a dog (not a wolf) and use those characteristics to train him to be a good family companion and community member.

- Oh, and Joe, drop the alpha status obsession once and for all, please? It embarrasses all of us, including your dog.

Evidence

Frantz LA, et al. “Genomic and archaeological evidence suggest a dual origin of domestic dogs.” Science, 2016; 352:1228-1231.

Freedman AH, et al. “Genomic sequencing highlights the dynamic early history of dogs.” PLOS Genetics, 2014; 10;e1004016.

Gacsi M, et al. “Species-specific differences and similarities in the behavior of hand-raised dog and wolf pups in social situations with humans.” Developmental Psychobiology, 2005; 47:111-122.

Hare B. “The domestication of social cognition in dogs.” Science, 2002; 298:1644.

Jensen P, et al. “The genetics of how dogs became our social allies.” Current Directions in Psychological Science, 2016; 25:334-338.

Larsen G. et al. “Rethinking dog domestication by integrating genetics, archeology and biogeography.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 2012; 109:8878-8883.

Mech LD. “Alpha status, dominance, and division of labor in wolf packs.” Canadian Journal of Zoology, 1999; 77:1196-1203.

Miklosi A, et al. “A simple reason for a big difference: Wolves do not look back at humans, but dogs do.” Current Biology, 2003; 3:763-766.

Range F and Viarnyi Z. “Tracking the evolutionary origins of dog-human cooperation: The ‘Canine Cooperation Hypothesis.'” Frontiers in Psychology, 2015; 5:1582

Note: This is not a comprehensive reference list. Rather, it includes studies that were discussed in the chapter and additional readings. For complete bibliographies, see the full list of books and textbooks at the conclusion of Case’s book, Dog Smart.

Linda Case is a canine nutritionist, science writer, and companion animal consultant who uses positive reinforcement and shaping techniques to modify behavior in dogs in basic level through advanced classes.

Wonderful article, thanks.

Just curious, was one of those dog skull photos meant to be of a wolf, for comparison? The “majestic wolf” photo isn’t loading.

Thanks

“There are few reports of wolves seeking higher positions in their pack” – Even though wolves are not constantly challenging their position; does not erase that there are positions no matter how hard anyone tries. These positions are rarely challenged because they are set in place early on and with each pack member playing their part in everyday activities such as socializing and hunting – the wolves enjoy and benefit from their present set structure. The whole argument on how close wolves are to present day dogs can be put aside – they both share a common ancestor and both have been observed countless times and proven to utilize hierarchy whether in packs or in households. What the conversation with ‘Joe’ or anyone else should focus on is how you should appropriately train your dog. It is indeed important that your dog knows you are it’s owner and important to acknowledge – the leader. Yet, this does not mean you need to bully your dog during training, or be forceful or nasty – instead, you should remain calm and assertive. There are many ways to show you are a pack leader or “Alpha” that do not involve intimidation or force, for example with dogs who have an issue with lunging for their food and forcefully jumping up on the owners; trainers have utilized a technique of having the dog learn to wait while you present it’s bowl, and then you pretend to eat some of the kibble before lowering the bowl to the dog and releasing it to it’s food. This technique is done based on the fact that those higher in position eat first (something documented in BOTH wolf and dog behavior) and involves no harsh treatment. With repetition; the wait command combined with the leadership display has proven effective. After all, a dog WILL NOT jump up in that manner on someone it truly sees in a position above it’s own. My point in saying all of this is that instead of people trying to convince inquirers and owners that dominance and/or hierarchy does not exist and plays no part in safety or training – they should instead educate people on ways to train without being harsh or forceful, proper use of corrections included.

It is also inaccurate that dogs do not form packs. Stray and feral dogs do roam in packs, most commonly seen outside the states. These groups come in handy when it comes to finding resources and may even serve as protection for the members. Humans have been attacked many times when one of the leading or more outgoing dogs in the group decide to bite and the rest of the group jumps in and begins attacking as well, a.k.a ‘pack mentality’. Thankfully other humans have been near by for many of the documented cases and were able to provide help.