I took my two dogs—Woody, age 9, and Boone, age 3—to see their vet a week ago. The night before their appointment, I groomed both dogs and trimmed their nails. Both dogs were due for a Leptospirosis vaccine, and Woody also was due for a rabies vaccine. Beyond that, my only concerns were about a few lumps on Woody. He has several small lumps that the vet mapped at his exam a little more than a year ago, and I was worried that a couple of them had grown. Also, I wasn’t looking forward to being chided for allowing him—nay, facilitating him—to gain a few extra pounds this winter.

But I wasn’t at all expecting the health problems that my vet found.

After a peek in Woody’s ears, she said matter-of-factly, “He’s got an ear infection.” Now, about three days prior, on a walk out in our local wildlife area, he had gone swimming in a lake, and in the course of that swim, had gotten water in his ear. He hates getting water in his ears, and he shook his head and held it crookedly for the remainder of our walk—but by the time we drove home, he had seemingly forgotten all about it and I hadn’t noticed any more head-shaking or a head tilt.

The infection wasn’t severe—though, without treatment, it probably would have gotten more severe. The vet prescribed a thorough ear-cleaning, plus a prescription ear-drop put in his ears once a day for seven days.

Other than that, she measured all of his lumps, and found that a couple of them had grown, but not by very much. On his last lump-exam, she had extracted a bit of fluid from several, and was satisfied that they are lipomas.

I declined blood tests on this visit, but will ask for them on our next visit.

Then it was Boone’s turn. I was quite confident she wouldn’t find anything wrong with Boone—but she did.

“He’s got pyoderma,” she said after running her hands through his coat as he rolled on his back on the floor of the exam room. “What?!” I exclaimed. I hadn’t noticed anything wrong with his skin or coat, and I had examined him very thoroughly the night before (I thought).

But then she pointed out some redness on his tummy and chest, and said, “Look; this is an epidermal collarette.” She pointed to a small round mark on his skin, and then another. I was astonished. About two years ago, I was editing an article about folliculitis—another word for pyoderma—and I had been tasked with trying to find a stock photo of epidermal collarettes. I hadn’t been able to find a stock photo of one anywhere; finally the veterinarian/author was able to find one for us to run with the article. But here they were on my own dog! Ack!

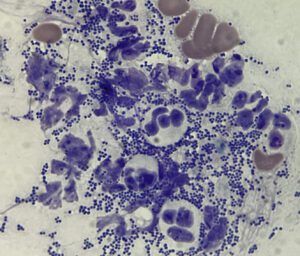

The vet also pointed out some small things that looked like pimples. Perhaps because I was so aghast at not being observant enough about my own dog’s skin, she said, “We’ll lance one of those and I’ll put some of the exudate on a slide and stain it so you can see the bacteria,” she said.

She did all those things and DANG if that slide wasn’t just LOADED with bacteria. Poor Boone was fighting an infection of his own!

Even though I had been rubbing Boone’s tummy when I had clipped his nails the night before, and I had noticed that his skin was a very little bit red here and there, I hadn’t thought it was very serious. Again, when we had been out in the wildlife area a few days before, he had been running through some reeds at the edge of the lake (in vain pursuit of ducks), and I just assumed the redness was irritation caused by the reeds. I certainly hadn’t noticed him licking or scratching at the area. But here we were, with a skin infection!

My vet gave me the option of putting Boone on oral antibiotics, or to start with a topical approach: medicated baths twice a week for a couple of weeks, and spraying his skin twice daily with an antibacterial solution. Though it’s a lot of work, I opted for the latter, in an effort to not wreck his internal microbiome if we didn’t have to.

Anyway, while these two health problems that I hadn’t noticed aren’t terribly dramatic—it’s not like the vet had detected a previously undiagnosed fatal condition—they are good examples of why our dogs need to be seen by a primary care veterinarian at least once annually. While the expenditure can be significant (especially at visits when you do run blood tests), catching minor conditions before they can bloom into major ones is critical for keeping your dog healthy and comfortable. If your dog hasn’t seen a vet for a year, it’s time to make an appointment!

My dogs go twice a year with bloodwork once a year (unless otherwise indicated). My oldest dog is 7-8 years old and the youngest is 16 months. Fully agree that being proactive is wise.