As soon as a food is manufactured, it begins to undergo a variety of chemical and physical changes. It’s a basic law of the universe (the second law of thermodynamics) that everything degrades over time. This includes the proteins and vitamins in dog foods, but it’s the fats I worry about the most.

Dogs require fats in their diet. However, fats are among the most chemically fragile nutrients in dog food; they are the limiting factor to the shelf life of most dog foods. Fats that have degraded – gone “rancid” – can cause all sorts of health problems for dogs.

So how can owners make sure their dogs get the healthy fats they need in their diets, without exposing them to rancid fats? The following are my recommendations for how this can be accomplished – but first, let me explain why it’s necessary to take extra steps to make sure your dog is helped, and not harmed, by the fat in his commercial diet.

The Fats Dogs Need

Fat is a very important part of a dog’s diet – especially when you consider that dogs don’t have a biological requirement for carbohydrates at all. Dietary fats provide concentrated forms of energy for the dog, carry the fat-soluble vitamins, and supply the dog with essential fatty acids (fatty acids are the basic building blocks of fats; “essential” fatty acids are those that the dog’s body needs but can’t manufacture). A variety of fats are needed by the dog for healthy skin, hair, and immune function; regulation of the inflammation process; and prenatal development. On a molecular level, fatty acids contribute to the physical structure of all the dog’s cells.

Fats – and their building blocks, the fatty acids – represent a broad category of nutrients. Just as your dog needs to consume a variety of vitamins and minerals, he needs a variety and balance of fatty acids. Which ones? How much? Well, I’m afraid it depends on who you talk to. In my opinion (and that of many canine nutrition experts), the best answers come from analysis of the dog’s ancestral diet and from nutrition science. Using these tools, I’ve come to believe that most commercial diets leave dogs short of what they need in terms of dietary fat in two ways:

1. Commercial diets generally feature an incomplete offering and unbalanced array of fatty acids.

2. The fat in commercial dog foods is prone to developing rancidity.

These traits pose problems for dogs, but they are easily overcome.

Incomplete and Unblanced

Before domestication, the dog’s diet contained a complete range of fats, because the dog ate many different parts of the prey animal, which contain different types of fat:

– Muscle meat contains saturated fats (SFAs), monounsaturated fats MUFAs), and polyunsaturated fats (PUFAs).

– Storage fat contains primarily SFAs.

– Bone marrow contains primarily MUFAs.

– Organ fat contains mostly MUFAs and PUFAs.

– The fat that protects the organs consists primarily of SFAs.

– Eyes and brains contain mostly PUFAs, including DHA.

Scientists at the National Research Council (NRC) periodically review all the relevant literature on nutrition (for humans as well as companion and food animals) and issue recommendations for nutrient amounts, maximums, and minimums for each species. In 1985, the NRC recognized just one fatty acid, linoleic acid (LA, an omega-6 fatty acid and a PUFA) as being essential for dogs.

However, by 2006 (the year it released its most recent guidelines, Nutrient Requirements of Dogs and Cats), the NRC had updated its findings and listed four additional PUFAs as essential for dogs: arachidonic acid (AA, another omega-6 fatty acid considered essential for puppies), and three omega-3 fatty acids: alpha linolenic acid (ALA), eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA). In time, I suspect it will list even more fatty acids as essential for dogs, including gamma linolenic acid (GLA), conjugated linolenic acid (CLA), and probably more.

It’s in the PUFAs that we often find a balance of fats problem, primarily an improper ratio of omega-6 to omega-3 fatty acids and the lack of DHA. Most nutrition experts suggest that the ideal ratio of omega-6 to omega-3 fatty acids for the dog is between 2:1 and 6:1. But many chicken-based conventional dog foods are formulated with excessive amounts of omega-6 fatty acids, primarily LA. And since LA is converted in the dog’s body into AA, an oversupply of LA results in an excess of AA, which promotes inflammation and exacerbates many health problems, including skin disease, arthritis, and renal problems.

Most dog foods do not contain DHA – which offers so many benefits for dogs! – and those that do contain DHA have a higher probability of becoming rancid.

Fat Rancidity in Dog Food

All fats chemically react to and degrade with exposure to oxygen; this is called oxidation. Oxidized fats are said to be rancid; they have degraded from a nutritionally beneficial substance to one that is actually toxic to animals. When fats become rancid, the shape, structure, function, and activity of the fatty acid is profoundly changed. (The bad smell associated with rancid fats is caused by chemical by-products of fat degradation: aldehydes and ketones.)

Rancid fats reduce the nutritive value of the protein, and degrade vitamins and antioxidants. That bears repeating: rancid fat can so vastly reduce the benefit your dog can get from the proteins and vitamins present in his food, that he can suffer from protein and vitamin deficiencies. Rancid fats can also cause diarrhea, liver and heart problems, macular degeneration, cell damage, cancer, arthritis, and death. It’s good policy to avoid feeding rancid fats to our dogs.

All of the omega-3 fats are fragile – they turn rancid quickly – with the long chain omega-3 fats EPA and DHA among the most fragile.

The Goal, and Barriers to Reaching It

The scientific evidence is overwhelming: dogs who eat a diet with balanced fats – especially the proper relative amounts of omega-6 and omega-3 fats (including DHA, probably the most important fat for the brain and eyes) – are healthier and more intelligent than dogs who do not consume a proper balance of fats. Every cell, every organ of the dog’s body operates more efficiently when fortified with the right fats.

However, pet food regulators have not yet required pet food makers to reflect everything that nutritionists agree on regarding fats. As of 2012, the Association of American Feed Control Officials (AAFCO) has not included DHA in its “Nutrient Requirements for Dogs” – a table that is used as the basis for the legal claim of dietary completeness and balance for all commercial dog foods sold in the U.S. The AAFCO nutrient requirements address only minimum amounts of fat and LA.

Some pet food makers, or at least, some of the nutritionists working for the pet food makers, are cognizant of the benefits of including other fatty acids, even if they are not required in order for a food to be labeled as “complete and balanced.” Some of the most up-to-date companies now include DHA or fish or fish oil (the most common and readily available sources of DHA) in their commercial foods. DHA is especially important for puppies and pregnant dogs, so premium puppy foods today often include fish or fish oil.

I strongly believe that it’s important for dogs to receive adequate amounts of DHA (in particular) and a diet that contains a balanced array of saturated, monounsaturated, and polyunsaturated fats. That said, I don’t think the ideal fat balance is best supplied by commercial foods, and here’s why: the fats needed to complete and balance a dog’s diet are too fragile to survive typical dog food production, handling, and storage.

I suspect that the state feed control officials (the voting members of AAFCO, which establishes the nutrient requirements for “complete and balanced” dog foods) are hesitant to require DHA (as the most compelling fatty acid) in dog foods because, at least with today’s technology, this expensive fat is just too fragile to be included in a product meant to be kept on the shelf for up to 12 to 18 months and left open in the kitchen for weeks.

Extrusion (where the food is quickly cooked under high pressure, the way most dog foods are produced) and long-term storage make it likely that any DHA present in the food oxidizes. In discussing fats in pet food, the 2006 NRC’s Nutrient Requirements of Dogs and Cats stated, “Many of the PUFAs in the diet, such as those from fish, undergo peroxidation during processing and storage before ingestion.” Peroxidation means the fats turn rancid. And rancid DHA is worse for the dog than no DHA at all.

Challenge for Commercial Dog Food Producers

What about all those pet food companies that do include DHA in their products? How do they ensure that the DHA (and other fragile fatty acids) don’t become rancid before the dogs eat them?

All the studies and nutrient analyses tests I’ve seen on the DHA content of dog foods were conducted at or very close to the time of manufacturing, when the foods were fresh, or were accelerated studies under laboratory conditions, not under real-world conditions.

For example, most dog foods move from the manufacturer via truck to a warehouse, via a truck to a retailer, and then to a home, where they may be open for 30 or more days before all the food is consumed. The food may be exposed to several temperature cycles, which is stressful for all the polyunsaturated fats (especially DHA), and may be six months old (or older) before it’s fed. How much DHA is left under these rough, but not atypical, conditions? How many of the fats are rancid?

For this article I wrote to probably every dog food manufacturer in North America, including all the big companies. I asked them if they had real world data: “Can you tell me what’s happened to the fats, especially DHA, by the time the dogs eat it?” I received no independent data in reply. Many companies responded but had no data to offer. Others gave me access to their in-house and consultant nutritionists, with whom I had several interesting conversations about long-term testing programs. (These yielded several iterations of one fascinating fact: Dogs can detect rancid fats, through smell, better than any laboratory equipment!)

A few companies provided me with data from accelerated testing – close, but not what I asked for. No company sent me independent test reports showing what happens in real-world conditions to the fragile fats by the time your dog eats the food.

Recommendations

In light of all of this information, I offer the following recommendations so that dogs who eat a commercial diet can get the fats they need, without being exposed to rancid fats. Dog owners can either:

1. Give your dog commercial foods that do not contain fish, fish oils, or DHA, and add them yourself; or

2. Buy recently produced commercial foods with added fish, fish oils, or DHA.

I think the best choice is to feed naturally preserved foods that meet freshness guidelines (described in detail below) and that do not contain fish, fish oil, or DHA; then add fresh, high-quality fish or krill oils or sardines yourself.

The Best Way to Add DHA: Sardines

The best way to add EPA and DHA is to feed sardines to your dog once a week. If you add fish oil to your dog’s food, replace the fish oil with sardines. While many of the studies showing the significant body and brain benefits of consuming DHA were conducted with fish oils, I think sardines are superior for many reasons.

Sardines, a sustainable fish with low mercury loads, are high in protein, and provide a complete range of trace minerals, including natural forms of zinc; a full complement of vitamins including D, B12, E and K; a full range of antioxidants; and other known (and, I’m sure, unknown) nutrients. The triglyceride and phospholipid forms of DHA found in sardines are more absorbable and stable than the ethyl ester forms in most fish oils, and may be more effective for improving brain functions and preventing cancer.

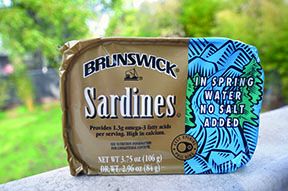

The best canned sardines for dogs are those in water with no salt added. Avoid sardines packed in soy, corn, sunflower, safflower, or other omega-6 rich oils. If my recommended amounts call for 1¼ cans of sardines, it is okay to feed two cans in one week of the month, and the other weeks feed just one can. Use the entire can of sardines within two days after opening it, and refrigerate the open can, so that the fragile fats do not go rancid.

If your dog doesn’t like sardines, or you don’t like the smell of sardines on your dog’s breath, use fresh, human-grade fish or krill oil gel caps. Don’t overdo it! EPA and DHA, like most nutrients, provide wonderful health benefits in small amounts, and are detrimental in excess amounts or without sufficient antioxidant protection. Feed small amounts (0.2 to 1 gram of high-quality EPA + DHA per day for a 45-pound dog) and you’ll probably make your dog smarter and healthier. Feed much larger amounts and your dog will probably slow down mentally and age at a faster rate.

Here are my sardine recommendations for adult dogs. Feed twice this much to puppies and pregnant or lactating females.

Dog’s 3.75-oz can

Weight sardines

5 lbs 1/4 can per week

15 lbs 1/2 can per week

25 lbs 5/8 can per week

50 lbs 1 can per week

100 lbs 1 3/4 cans per week

A 3.75-ounce can of sardines has about 200 calories, so reduce the amount of dry food given on “sardine days” accordingly. Rule of thumb: One can of sardines in water has about the same number of calories as ½ cup of most dog foods.

You can substitute canned wild Alaska pink salmon (the bones are edible), oysters (a great source of zinc, especially important for pregnant and lactating females), and other fresh, frozen, or canned wild ocean fish for sardines. Pacific oysters are probably better than Gulf of Mexico oysters, especially after the BP oil spill in 2010, and safer than canned oysters from China. Never feed raw salmon or trout, especially Pacific salmon, because it may contain a bacterium that can kill dogs.

Further Considerations While Buying Dog Food

The following are a few more things to think about if you feed dry foods to your dog. Some of the bullet points will help you select healthier, fresher foods for your dog; some will help you keep that food in the best possible condition until your dog has eaten it all. The final point is a warning about supplemental fish oil.

– Determining produced-on date. A few pet food makers include both a “produced-on” date and a “best by” date on their products; that’s ideal. Most, however, just use a “best by” date as part of the date/code on the label.

To determine how fresh a food is you need to calculate the produced-on date. Ask the manufacturer (almost all of them have toll-free numbers) what the shelf life is for the product you’re curious about. Most dry foods are given 12-month shelf lives, but some foods are given 18 months.

If a food has a best-by date of December 2013, and the manufacturer gives the food a 12-month shelf life, the food was produced December 2012.

– Freshest! For the freshest foods, buy chicken-based foods from retailers who sell lots of that food and get frequent deliveries, and who always rotate. Some imported exotic meats may only be imported once a year, so even freshly made exotic foods may use one-year-old meats.

– Natural or synthetic preservatives? Preservatives are used in dry dog foods to slow down the oxidation of the fats. Natural preservatives such as mixed tocopherols are considered to be less harmful for dogs than artificial preservatives, but they do not prevent oxidation (rancidity) for as long as artificial preservatives do.

If you’re planning on keeping a food toward the latter half of its “best by” date, your dog may be better off with a food that is preserved with a synthetic antioxidant such as ethoxyquin. Personally, I think the dangers of rancid fats are greater than the problems posed by synthetic antioxidants.

– Buying foods in foil bags. Typical paper / plastic dog food bags provide excellent moisture and insect barriers, but are only moderate oxygen barriers. Foil bags provide excellent moisture, insect, and oxygen barriers and are best for long-term preservation of nutrients.

Foil bags are expensive and may have much larger environmental impacts than typical bags. I suggest buying foods in foil bags only when you need to store unopened bags of food for long times. If you follow the guidelines above, the extra protection and cost of foil bags won’t be necessary.

– Food with the longest shelf-life. If you want to stock your summer cabin with unopened bags of dog food for a year, low-fat beef foods without fish oils preserved with ethoxyquin and packaged in foil bags will give the longest shelf life. Beef and bison meats contain fewer polyunsaturated fats than do chicken and turkey foods, and therefore they usually have longer shelf lives.

– Trust your nose – and your dog’s nose. The most sensitive tests for rancid fats are trained human and canine noses. If the food doesn’t smell right to either of you, don’t feed it.

– Storing food. Freezing is the best way to preserve pet food, but it’s not only impractical for most of us, but also unnecessary when following the freshness guidelines (on the facing page). Store in dry, cool locations. If using a food container, keep the food in its original bag and place the bag in the container.

– Special caution. At dog shows I’ve seen gallon-sized, clear, plastic jugs of fish oil offered for sale. The price per serving might be appealing if you have a lot of large dogs, but these containers scare me. The lightweight plastic provides little barrier to air and transmits light, which causes photo-oxidation. Unless you know the manufacturer and the freshness of the fish oil, and have enough dogs to use the oil very quickly, avoid these products. Remember, no DHA is better than rancid DHA.

Manufacturers, Please Challenge Me

What can the consumer expect is in the food when it’s fed? The state-of-the-art in packaging, natural antioxidants and the stability of forms of DHA keep improving (for example, algal meal provides DHA in more stable forms), but I have yet to see real-world data on the stability of dry foods with fish oils or DHA added.

Accelerated stability tests provide some information, but are not sufficient for me to change my recommendations. Real-world, long-term tests are essential because changes in temperature and physical jostling during distribution add stress to the fats, and mixed tocopherol preservation systems may not be effective under stressful conditions. The best data will include palatability tests as well as chemical tests. Dogs are more sensitive to rancidity than peroxide value and free fatty acids tests.

Steve Brown is a dog food formulator, researcher, and author on canine nutrition. In the 1990s he developed one of the leading low-calorie training treats, Charlee Bear® Dog Treats, as well as the first AAFCO-compliant raw dog food. Since 2003 he has focused on research and education. He is the author of two books on canine nutrition (See Spot Live Longer, now in its 8th printing, and Unlocking the Canine Ancestral Diet (Dogwise Publishing, 2010); and a 40-page booklet, See Spot Live Longer the ABC Way. He is also a formulation consultant to several pet food companies.

Just a note on the foil dog food bags. I recently had a hair analysis done on my 45#, 4 year old male dog. His aluminum was extremely high. We have always, until the hair analysis, fed him Fromm Four Star Dry Dog Food. These foods are all packaged in what appears to be inner (and possibly outer) foil bags. To our knowledge, he has never been exposed to aluminum from any other source, except possibly the food in the bags! I now feed him human grade dark meat chicken and vegetables, with a few recommended supplements only – including sardines – about one 4+ oz. can per week, packed in water.

So I keep reading about how often I can give my boxer mix / 14 months dog sardines. I’m trying to meet the protein requirement for her and one can is 23g of protein. I also give her black beans. However, I don’t seem to find any information on why I cannot give her the whole can and why I should only feed her 2 can/ week ?

Can I freeze the unused portion of sardines for later consumption? I don’t see why not, but just checking.

I love reading all this blogs a lot of information thanks!!!

Would frozen sardines be better than canned? Canned sardines are cooked, usually twice, and therefore have already lost some of the nutrients, plus there is the chance of BPA leaching from the can.

Is this recommendation still accurate? It says 1 can per week for a 50 lb dog, but his ABC booklet says 2 cans?