[Updated May 22, 2018]

I grew up with a storybook grandmother, “Nana” to my sister and me. Nana was a great cook and regularly expressed her love through sumptuous meals and comfort foods. Her home was definitely the place to be on all food-oriented holidays, including the ultimate all-American food holiday, Thanksgiving. Like many Americans on this day, my family gorged on all that Nana placed on her overloaded dining-room table – mashed potatoes, stuffing, butternut squash, warm rolls, salads, corn casserole, and, of course, the mandatory roasted turkey. Following this annual feast, my sister and I would fall into food-induced stupors, sleeping off our over-indulgence for several hours before rousting ourselves to eat one more piece of pie.

A number of years later I learned that my post-feast drowsiness was presumably caused by a specific nutrient in turkey, the amino acid tryptophan. This theory, first put forth by a nutritionist, proposed that turkey meat contains unusually high levels of tryptophan.

Once absorbed, tryptophan is used by the body to produce serotonin (a neurotransmitter) and melatonin (a hormone). Melatonin helps to induce feelings of drowsiness (i.e., enhances sleep) and the neurological pathway through which serotonin works has anti-anxiety and calming effects. Therefore, the theory goes, after consuming a high-protein meal, in particular one that is high in tryptophan, the body’s production of melatonin and serotonin increases, which in turn causes drowsiness, reduced anxiety, and a calm state of mind. Presto – the post-turkey coma!

The tryptophan/turkey theory became so popular and widespread in the early 1980s that nutrient-supplement companies decided to bypass the turkey part of the equation altogether and began producing and selling tryptophan supplements (L-tryptophan). These were initially promoted as sleep aids and to reduce signs of anxiety. However, as is the nature of these things, the promoted benefits of L-tryptophan rapidly expanded to include, among other things, claims that it would enhance athletic performance, cure facial pain, prevent premenstrual syndrome, and enhance attention in children with attention deficit-hyperactivity disorder. (My personal favorite was the promotion of L-tryptophan as a treatment for Tourette syndrome.)

L-tryptophan enjoyed a robust reputation as the nutrient for “all that ails ye'” until 1989, when it was found to be responsible for causing eosinophilia-myalgia in more than 5,000 people, killing at least 37 and permanently disabling hundreds. The US Food and Drug Administration quickly banned its import and sale as a supplement. Although the problem was eventually traced to a contaminant in a supplement that was imported from a Japanese supply company (and not the L-tryptophan itself), the ban remained in effect until 2009. Today, L-tryptophan is once again available as a nutrient supplement, but it has never regained its earlier popularity as a supplement for humans.

Tryptophan and Dogs

It’s odd that L-tryptophan was largely ignored by the dog world until a research paper published in 2000 suggested that feeding supplemental L-tryptophan might reduce dominance-related or territorial aggression in dogs1 (see references on page 10). The researchers also studied dogs with problem excitability and hyperactivity, but found no effect of L-tryptophan on either of these behaviors. However, the paper led to the belief that tryptophan supplementation was an effective calming aid in dogs (which it definitely did not show in the study) and as an aid in reducing problem aggression.

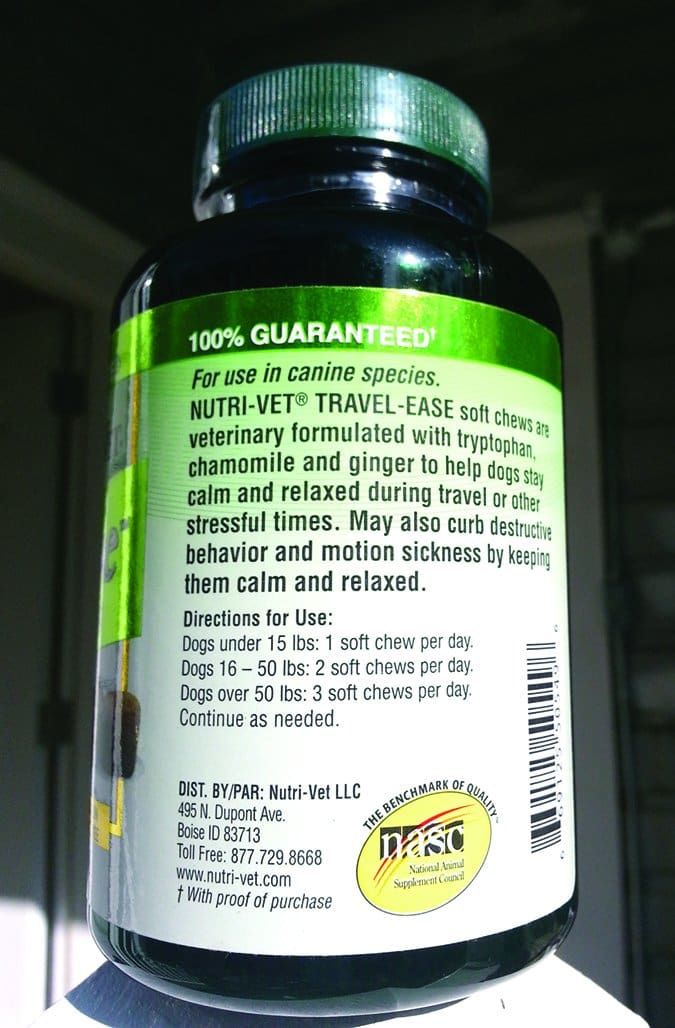

Today, a number of L-tryptophan supplements are marketed for reducing anxiety and inducing calmness in dogs. Interestingly, none of these product offer pure L-tryptophan; all of them include other agents that are purported to have a calming effect on dogs, such as chamomile flower, passionflower, valerian root, or ginger.

So, what does the science say? Does eating turkey or taking an L-tryptophan supplement reduce anxiety and induce calmness? Can it be used as an effective nutrient supplement to reduce anxiety-related problem behaviors in dogs?

The Turkey Sleepiness Myth

It is a myth that consuming turkey induces drowsiness or reduces anxiety. The theory fails on several counts. First, turkey meat does not actually contain a uniquely high level of tryptophan. The amount of tryptophan it contains is similar to that found in other meats and is only half of the concentration found in some plant-source proteins, such as soy. Do you get sleepy after gorging on tofu?

Second, researchers have shown that the amount of tryptophan that is consumed after a normal high-protein meal, even one that contains a lot of tryptophan, does not come close to being high enough to cause significant changes in serotonin levels in the blood or in the synapses of neurons, where it matters the most.

Third, to be converted into serotonin (and eventually into melatonin), tryptophan that is carried in the bloodstream following a meal must cross the blood-brain barrier and enter the brain. This barrier is quite selective and only accepts a certain number of amino acids of each type. Tryptophan is a very large molecule and competes with several other similar types of amino acids to make it across the barrier. Following a meal, especially if the meal is high in protein, tryptophan does increase in the blood and is pounding at the blood-barrier door for access. However, it is also competing with other amino acids that are also at high levels (and turkey contains all of ’em). As a result, very limited amounts of tryptophan make it into the brain for conversion following a meal that includes lots of other nutrients.

So, why so sleepy? The real explanation for the drowsiness and euphoria that we all feel following a great turkey dinner at Nana’s house is more likely to be caused by simply eating too much (which leads to reduced blood flow and oxygen to the brain as your body diverts resources to the mighty job at hand of digestion), imbibing a bit of holiday (alcoholic) cheer, and possibly, eating a lot of high-carbohydrate foods such as potatoes, yams, and breads, which leads to a relatively wider fluctuation in circulating insulin levels. Whatever the cause, don’t blame (or credit) the turkey or the tryptophan.

Tryptophan: Flying Solo

That established, the erroneous focus on turkey did have some positive consequences in that it led to a closer look at tryptophan’s potential impact on mental states and behavior when provided as a supplement. As a serotonin precursor, tryptophan (and its metabolite 5-hydroxytryptophan, or 5-HTP) has been studied as either a replacement or an adjunct therapy for serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SRRIs), medications that are commonly used to treat depression in people and are sometimes prescribed as treatment for anxiety-related behaviors in dogs.

Although limited work has been conducted regarding the effects of tryptophan supplementation in dogs, several informative papers did follow the initial dog study of 2000:

Tryptophan and Anxiety

Researchers at Wageningen University in the Netherlands studied a group of 138 privately owned dogs with anxiety-related behavior problems2.

Study design: Half of the dogs were fed a standard dog food (control) and half were fed the same food, formulated to contain supplemental L-tryptophan. Neither the owners nor the researchers were privy to dogs’ assigned groups. In other words, this was a “double-blind, placebo-controlled study” (see my book Dog Food Logic for more about studies), the “gold standard” of research designs. Dogs were fed their assigned diet for eight weeks, during which time the owners recorded any behavior changes they observed. At the end of the study, the researchers also performed a set of behavior evaluations to assess the dogs.

Results: Although blood tryptophan levels increased significantly (by 37 percent) in the dogs that were fed supplemental tryptophan, neither the owners nor the researchers observed any difference in behavior between the supplemented group of dogs and the control dogs. There were moderate changes in behavior over time in all of the dogs, but this change was attributed to a placebo effect (more about placebos in next month’s column). Overall, supplementation with L-tryptophan demonstrated no anxiety-reducing effects in the dogs enrolled in this study.

Tryptophan and Abnormal/Repetitive Behaviors

A group of 29 dogs was identified3, each presenting with a form of abnormal-repetitive behavior, either circling, anxiety-related lick granuloma, light chasing/shadow staring, or stool eating. (Note: One might question the inclusion of stool-eating in this study, since many pet professionals consider eating feces to be a form of scavenging behavior that is normal and common in the domestic dog.)

Study design: This was another double-blind and placebo-controlled study. In addition, the researchers used a “cross-over” design in which half of the dogs are first fed the control and the other half are first fed the test diet for a period of time and are then all switched to the alternate diet for a second study period. This is a well-accepted study design that is helpful when a researcher has a limited number of subjects; it also helps to control for the placebo effect.

The dogs were treated for two-week periods and the frequencies of their abnormal behaviors were recorded daily.

Results: The researchers reported no effect of supplemental L-tryptophan on the frequency or intensity of abnormal/repetitive behaviors. Although the owners reported slight improvements over time, this occurred both when dogs were receiving the supplemental tryptophan and while they were eating the control diet (there is the insidious placebo effect again).

Limitations of this study were that it was very short term and it targeted uncommon behavior problems that are notoriously resistant to treatment. Still, this study did not provide any evidence to support a use of tryptophan supplementation for repetitive behavior problems in dogs. (So, to all you folks who live with poop-eaters: sorry, no easy answer here with L-tryptophan.)

Tryptophan-Enhanced Diet and Anxiety

Dogs with anxiety-related behavior problems were fed either a control food or the same food supplemented with L-tryptophan plus alpha-casozepine, a small peptide that originates from milk protein4.

Study design: This was a single-blind, crossover study in which only dog owners were blinded to treatments. All of the dogs were first fed the control diet for eight weeks and were all then switched to the test diet for a second eight-week period. Because the treatment group always followed the control in this study design, it is impossible to distinguish between a placebo effect and an actual diet effect in this study. (Note: This is a serious research design flaw that the study authors mention only briefly.)

Results: A small reduction in owner-scored anxiety-related behaviors was found for four of the five identified anxiety problems. However, in all of the cases, the initial severity of the problems was rated as very low (~1 to 1.5 on a five-point scale in which a score of 0 denoted an absence of the problem and a score of 5 denoted its highest severity), and the change in score was numerically very small, though statistically significant. This is not surprising since there is not very much wiggle room between a score of 1 and a score of 0. Finally, given that the food was supplemented with both L-tryptophan and casozepine, conclusions cannot be made specifically about L-tryptophan.

Take-Away Points for Dog Folks

First, forget the turkey. While it can be a high-quality meat to feed to dogs (especially if you select a food that includes human-grade meats or are cooking fresh for your dog), turkey contains no more tryptophan than any other dietary protein. Feeding turkey to your dog will not promote calmness (unless you allow him to stuff himself silly along with the rest of the family on Thanksgiving Day – a practice as unadvisable for him as it is for you).

Second, keep your skeptic cap firmly in place when considering the effectiveness of supplemental L-tryptophan or a tryptophan-enriched food as a treatment for anxiety-related problems. The early study in 2000 reported a modest effect in dogs with dominance-related aggression or territorial behaviors but found no effect in treating hyperactivity.

Subsequently, two placebo-controlled studies reported no effect at all, and the single study that reported a small degree of behavior change could not discount the possibility of a placebo effect.

Human nature encourages us to gravitate toward easy fixes for all things that ail our dogs. Hearing about a nutrient supplement or a specially formulated food that claims to reduce anxiety and calm fearful dogs is powerful stuff for dog owners who are desperate to help their dogs. These types of claims are especially appealing because anxiety problems can have a terrible impact on a dog’s quality of life and are often challenging to treat using the standard (and proven) approach of behavior modification.

An additional risk that must be mentioned regarding our inclination to gravitate toward unverified nutritional “cures” is that well-established approaches such as behavior modification may be postponed or rejected by an owner who instead opts for the supplement, wasting precious time that could actually help a dog in need. Until we have stronger scientific evidence that demonstrates a role for L-tryptophan in changing problem behavior in our dogs, my recommendation is to enjoy the turkey, but train the dog.

Cited References:

1. DeNapoli JS, Dodman NH, Shuster L, et al. Effect of dietary protein content and tryptophan supplementation on dominance aggression, territorial aggression, and hyperactivity in dogs. J Amer Vet Med Assoc 2000; 217:504-508.

2. Bosch G, Beerda B, Beynen AC, et al. Dietary tryptophan supplementation in privately owned mildly anxious dogs. Appl Anim Behav Sci2009; 121:197-205.

3. Kaulfuss P, Hintze S, Wurbel H. Effect of tryptophan as a dietary supplement on dogs with abnormal-repetitive behaviours. Abstract. J Vet Behav 2009; 4:97.

4. Kato M, Miyaji K, Ohtani N, Ohta M. Effects of prescription diet on dealing with stressful situations and performance of anxiety-related behaviors in privately owned anxious dogs. J Vet Behav 2012;7:21-26.

I really resent the implication that those of us trying to find something to reduce anxiety or unwanted behaviors are looking for a quick fix instead of training. Sometimes it is just not that simple!

I am a health care professional with about 13 yrs of experience sing amino acid supplements; as a therapist and parent, I am loathe to suggest that any kind of quick fix is appropriate. But as yo mention in the text, tryptophan competes with other proteins for absorption. As the studies you report fed the dogs for with tryptophan, this suggests that more research is needed giving dogs the supplement on an empty stomach. I always emphasize this to clients and have fond when they accidentally take these amino acids with food and then switch, they report better results.

I take tryptophan myself. It’s a serotonin precursor, so if ur short on this, tryp can help. The element missing in the research is light. The call to make serotonin is the blue content of light. Daylight. My situation manifests as blue light anxiety. Bit hard to describe. Its like the feeling u get when ur late for something but trapped in traffic. Winter strong white overcast days are worst. Clear blue sky days are best. Go figure. Anyway, tryp disappears it. Without it, im a walking blue light meter. LED light is all based on a blue pilot laser that can really jazz the anx when bright. Somewhat stimulating at first, turning around 1.5 hrs, anx at 3 hrs. Short sleep as well.