Giant-breed dogs can be a hoot. It’s fun to see them in cars, looking for all the world like bears being taken for a drive. It’s lovely to witness a well-mannered Great Dane, St. Bernard, or Great Pyrenees walking nicely on a leash and greeting admiring passers-by in a calm, friendly fashion. But it needs to be said that sometimes, those really big dogs can pose some really big behavior challenges for their owners.

ISSUES OF SIZE WITH GIANT DOG BREEDS

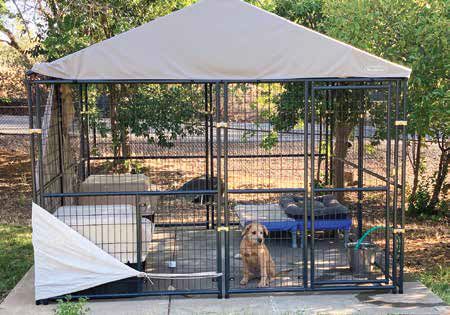

Some of the problems they can present to their family members are simply related to their extraordinary size. If you’re seated at the dinner table and your Irish Wolfhound strolls by, his head may pass over your plate even if he’s not trying to counter surf. You could purchase an extra-tall dining room table with bar stools for chairs or consider other management solutions (baby gates, mat training, crates, tethers) just to keep the hound drool out of your dumplings.

Sometimes a giant dog’s mere presence can trigger other dogs. Smaller dogs can be intimidated by the size and bulk of a 100- to 200-pound dog. Even if the big guy has no ill intent, fights can erupt as a result of a smaller dog’s stress. Imagine the logistics of breaking up a dog fight if one of the participants weighs 100-plus pounds!

While many of the big dogs (although not all) are truly gentle giants and get along well with other dogs, there doesn’t even need to be conflict for an injury to occur – a misstep of 200 pounds of dog onto an 8-pound Pomeranian (or a small child!) can cause significant bruising and/or broken bones. Caretakers of giant dogs must use common sense and management when selecting canine and human playmates for their oversized canine family members.

WITH GREAT SIZE COMES GREAT RESPONSIBILITY

Whether you already have one or are thinking of adopting, living with a dog who weighs as much as or more than you and towers over your head when standing on his hind legs, means that it’s incumbent on you to make sure the dog is super well-socialized and well-trained.

The fact that these dogs have the potential to cause more harm than smaller dogs – whether by just pulling their owner off their feet or knocking someone over or through an act of actual aggression – means that their owners bear more responsibility to do everything in their power to help their dogs become safe members of their community.

It’s important for all puppies to begin their training and socialization programs starting at the age of 8 weeks – but this is critical for the giant breeds. You really want them to learn polite leash walking and have a foundation of good manners before they are big and strong enough to overpower you (which may come as early as 6 or 7 months, depending on your size). They must be well socialized before they start lunging at visitors and other dogs and can drag you to the target of their playful, reactive, or aggressive behavior.

Your first step? Get thee to a good force-free puppy kindergarten class while your pup is still small – starting at 8 weeks.

BIG DOG TRAINING BASICS

The giant breeds learn exactly the same way other dogs do: Behaviors that are reinforced repeat and increase, and behaviors that don’t get reinforced will go away (extinguish). Remember that not all reinforcement comes from humans; inadvertent environmental reinforcement works quite well to encourage your dog to persist with unwanted behaviors.

So, for example, if you left food on the counter and your giant dog helped himself to it, he was reinforced for the behavior of looking for and helping himself to food from the counter and will surely do it again. Hence the importance of assiduous management, especially for a dog who can casually snag a thawing turkey off the counter without lifting his paws off the floor!

Basic good manners are important for all dogs. There are some, however, that can be particularly useful for the oversized canine:

- Polite leash walking. This is mandatory; you must be able to control your giant dog. The sooner you install good leash manners, the more he can accompany you places, engage in various activities, and enjoy a full and enriched life. If you cannot control him on leash, he’ll be left home a lot. If and when you do take him on outings, he’s likely to get himself (and you!) into trouble. (For training tips, see “Polite Leash Walking,” September 2021.)

- Appropriate greeting. Few people appreciate having a big dog barge into their face, covering them and their clothes with slimy spit. Friends will be happier about interacting with yours if he comes up to them and sits politely. (See “How to Teach Your Dog to Greet Nicely,” September 2018.)

- Mat training. A handy behavior for many dogs, mat training is an even more vitally important tool to manage your giant dog’s imposing presence. Family members and visitors can relax knowing that your dog will stay politely parked on his mat while you dine and socialize. (See “Mat Training Tips,” January 2020.)

- Walk away. For this behavior, you teach your dog to do a 180-degree turn and move quickly in the other direction. This “emergency U-turn” behavior can help you and your dog avoid some serious scrapes. There may come a time in your dog’s life where he is so aroused that normal good manners fail. “Walk Away” can be the most useful cue in your repertoire to help your big guy move quickly and willingly away from potential trouble. (See “How to Teach Your Dog to Just Walk Away,” September 2018.)

BIG DOG GROOMING ETIQUETTE

Last, but by no means least, your plus-size pal must be comfortable with necessary husbandry procedures: vet exams, nail trimming, grooming, etc. No animal care professional looks forward to the confrontation with their four-legged clients, and the bigger the dog, the harder – and more dangerous – it can be to work with an unwilling or uncooperative subject.

Good puppy socialization classes include fun games to help your big-dog-to-be get comfortable with ear inspections, dental exams, paw handling, nail trimming, and all the other procedures and interactions that are an inevitable part of a dog’s life. A good veterinary-care provider will be on board with cooperative care procedures. And a good force-free professional can help you teach your dog invaluable consent husbandry procedures such as the Bucket Game. While you’re at it, don’t forget the muzzle training. (See “Cooperative Care: Giving Your Dog Choice and Control,” February 2021, and “Dog Muzzles Are Useful Tools When You Use Them Right,” February 2019.)

GO BIG!

The behavior and training challenges you face with your big dog are the same ones we see with smaller dogs. Due to their size, however, extra-big dogs can present these challenges in an extra-big way; hence the importance of teaching appropriate behaviors and addressing behavioral challenges as soon as possible. If you already have one of these plus-size dogs or you intend to adopt one in the future, plan to go big with your training, management, and behavior plans, too.