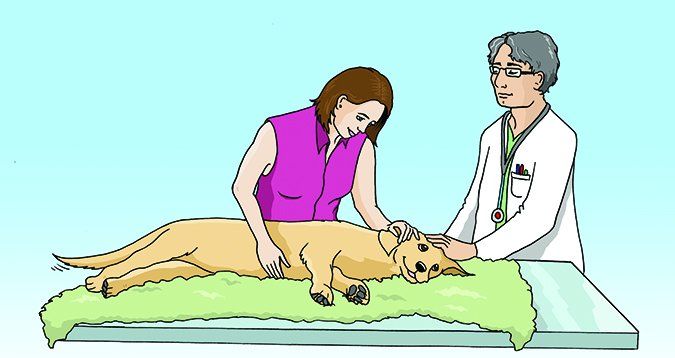

The final kindness we can do for beloved pets who are suffering from disease or painful effects of advanced age is to relieve and shorten their misery. Euthanasia should be painless and peaceful, giving a caregiver a last, loving embrace with her dog (or cat), and a memory of ending the pet’s life in a quiet, dignified, fear-free, trauma-free manner. Many of us are at our most vulnerable at this time, wracked with sadness and distracted with deep concern for our companions – and, unfortunately, this may cause us to fail to ensure that the end we want for our pets resembles our hopeful vision of a peaceful end in any way.

Twice in the past year I went to a veterinary hospital to have an animal companion euthanized. One was my 20-year-old cat, Yogi; the other was a beloved friend’s ancient, blind, deaf, Chihuahua, Hopper, whom I was fostering after my friend’s death. In each instance, I wanted a smooth transition from this life to the afterlife for these much-loved, suffering pets – and in each instance, I was horrified during the process by events that were out of my ability to foresee or control. That is, they were out of my control because I hadn’t foreseen them.

The stories were difficult to recount (they are described in “Pet Euthanasia Gone Wrong“), but as a tribute to these animals, who didn’t get the painless, peaceful end they were entitled to, I’d like to warn others about the things that can potentially go wrong during euthanasia. I want to stand at the edge of the world and scream, “No animal should suffer pain and terror at the end of her life during euthanasia, at the hands of a veterinarian!” Instead, I’ll try to turn my horrific story into an educational opportunity.

Look for Practitioners Dedicated to Fear- and Pain-Free Caregiving

There is no more appropriate time to engage the services of a practitioner trained in fear-free handling techniques than when it comes to euthanizing your pet. Fortunately, there are now at least three well-respected sources of education and certification for veterinarians and their staff (as wells as groomers, daycare providers, dog trainers, and other pet-care professionals) on the topic of handling animals in a way that does not cause them additional stress or pain.

Dr. Sophia Yin, a veterinarian with a special interest in animal behavior and positive reinforcement-based training, is widely credited with pioneering methods of safely handling animals for husbandry and veterinary purposes.

When Dr. Yin realized that more dogs were being euthanized because of behavioral issues than medical issues, she went back to school (after earning her doctorate in veterinary medicine in 1993). She earned a Masters degree in Animal Science in 2001 and started developing low-stress handling techniques in her veterinary behavior practice. She published a book about these methods, Low Stress Handling, in 2009.

After Dr. Yin’s death in 2014, her business partners continued her legacy by establishing a low-stress handling curriculum and certification for veterinarians, vet techs, and any other animal-care professionals who want to learn to handle companion animals with the least amount of stress and defensiveness possible.

Pets who are less stressed feel more at ease in a hospital, from the minute they walk through the door, throughout their examinations, until they leave. Several levels of Low Stress Handling Certification can be earned by veterinarians and their staff, as well as other animal-care professionals, through Dr. Yin’s legacy, Low Stress Handling University.

Another certification program designed to reduce stress in pets in a hospital environment is called Fear Free, which was founded by Dr. Marty Becker, a veterinarian with a practice in Idaho. Dr. Becker is also adjunct professor at several schools of veterinary medicine and has authored a number of popular books on animal health. Fear Free offers an ever-growing number of courses for veterinary-hospital staff on subjects that range from fear-free animal, transport, waiting rooms, examinations, and in-hospital protocols for sedation, anesthesia, and analgesia.

Individual Fear Free professional certification launched in early 2016. One of the next certifications that Dr. Becker plans to offer is called Compassion-First Pet Hospitals, wherein every aspect of a veterinary practice is designed with the animal patients’ emotional comfort as a priority.

Recently the American Animal Hospital Association (AAHA) began offering an online course in animal hospice and palliative care that includes euthanasia protocols that follow the Low Stress Handling and/or Fear Free philosophies. The certification program can be taken by veterinarians, vet techs, vet office staff, kennel workers, or anyone with an interest in this subject. See the AAHA web page for more information.

These are the only certification programs available to veterinary professionals. Courses in understanding companion animal behavior, body language, and the emotional state of pets were not taught in veterinary schools when Dr. Yin and Dr. Becker were students (I’m not aware of any veterinary schools that include this information in their curriculum even now), and both sought to address that educational void.

If you love your veterinarian, but you don’t think she is aware of these fear-free or low-stress handling educational resources, consider mentioning these certification programs the next time you and your dog see her. If she learned even a few tips on how to help pets be less anxious during vet visits, you’d all (client, patient, doctor, staff) be glad she did.

Confirm Your Vet’s Certification

It’s possible for a veterinarian to independently seek out advanced education and earn competence in animal behavior and low-stress handling techniques, just as Dr. Yin and Dr. Becker did. However, I learned the hard way that pet owners need to be vigilant and ask for confirmation of whatever “low stress” or “fear free” marketing claims are made by a veterinary practice.

As a dog trainer, body-language expert, former veterinary technician – and certified Fear Free Professional myself – I knew that I wanted a compassionate and trained veterinarian and staff to help facilitate a smooth, peaceful, and painless transition for my 20-year-old feline companion, Yogi. Having recently moved to a new area, I searched online for a veterinary hospital whose website referenced fear-free veterinary protocols. I was thrilled to find one about an hour away. The website had several mentions of fear-free visits and one whole page explaining how the practice owners made the hospital fear-free. When I called to make the appointment for Yogi, I asked whether they were versed in Fear Free protocols and was assured that they were.

But after not one but two traumatic euthanasia experiences at the hospital (see “Pet Euthanasia Gone Wrong“), I found myself wondering about how the practitioners could possibly have credentials of any kind in fear-free or low-stress handling. I looked at the website again – and was stunned to realize that the language on the website was all in lower-case; there were no logos indicating the practice had either Fear Free or Low Stress Handling certifications.

I next emailed the customer-service representative at Fear Free asking if this hospital or any staff member was certified by Fear Free. I received an email stating that no one in the hospital was certified and that a Fear Free representative would contact the hospital regarding the language on the practice’s website. Within a few short hours, the language on the hospital website was changed, and now references how the business strives to make its veterinary hospital experience “stress free.”

Lesson learned: Don’t fall for buzzwords. Ask for proof of training, certification, or independent study, and insist on making an appointment with only those individuals who received the training that you want your veterinarian and technician to have.

Pet Euthanasia Protocols

The veterinarian who euthanized my cat and my foster dog used the same drug, in the same way (intra-muscular injection) as a pre-euthanasia sedative. Both animals had a very strong adverse reaction to the injection of the drug; the injection traumatized them and their frenzied responses traumatized me.

The day after the second awful experience, I called the veterinary clinic and asked for the name of the pre-euthanasia drug that was used on my cat and dog.

The drug is called Telazol. It’s a mix of two other drugs, tiletamine and zolazepam. I called Zoetis, the company that makes the drug, detailing the reaction that my animals had. I wanted to find out if the drug had been used improperly, or if the reaction my pets had was typical.

The Zoetis representative told me that while Telazol is not contraindicated to use as a pre-euthanasia sedative, it’s not the drug’s intended primary purpose; its primary purpose is as an anesthetic on difficult-to-manage animals for short procedures such as wound management, not for a pre-sedation before euthanasia. In headline-size type, the Zoetis website says Telazol “Provides restraint or anesthesia for cats and restraint and analgesia for dogs undergoing minor procedures.”

I also learned that the drug can sting badly when administered intramuscularly (IM).

I posted my experience on a closed Facebook group for Fear Free Professionals and asked what drugs or combinations of drugs do they use for a painless, peaceful euthanasia. None of the veterinary professionals in the Fear Free group used this drug in the manner that this vet used it.

All the veterinarians who responded said they mixed Telazol with other drugs and administered it subcutaneously (under the skin, commonly referred to as “sub-q”) rather than IM, because it’s less painful that way. Some didn’t use this drug at all, preferring other drugs, such as the combination of xylazine and ketamine best known by its veterinary nickname, “pre-mix.” Several vets also noted that “pre-mix” can also sting when administered IM. When an animal is emaciated, or has very little muscle tissue (as in the case of many senior cats and dogs, including my two wards), these drugs can cause so much pain when administered IM, that many of these vets inject the drugs sub-q, instead.

The most important bit of information that I gathered is this: There is no single right way to administer a pre-sedation drug or drug cocktail to every animal, every time. Ideally, the veterinarian should take into consideration a number of factors:

- The patient’s species (cat, dog)

- The patient’s physiological condition (obese or thin; well-muscled or lacking adequate muscle tissue; good or poor circulation; etc.)

- The patient’s behavior (calm, or agitated and fearful)

In fact, if a veterinarian uses the exact same drug protocol on every single animal, or will tell you exactly what drug will be used over the phone (before seeing the animal), it’s a red flag; this is absolutely a case in which the veterinarian should see and assess the animal’s condition before deciding which drug or drug combination to use, and how it will be administered (intramuscularly or subcutaneously).

I understand that no practitioner can sedate and euthanize without causing pain or fear in every animal, every time. But now I also know that a skilled, caring practitioner should see and evaluate each animal as an individual, and customize the drugs used and the way they are administered for the unique needs of each animal.

Before Making an Appointment for Euthanasia, Ask These Questions

You will undoubtedly have a meeting with a veterinarian if your dog’s condition is such that you are considering euthanasia as an alternative to suffering for days or weeks from a condition that is slowly or painfully killing him. That’s the time to ask your veterinarian questions about her protocol for euthanasia and listen keenly to her answers; they will tell you if she’s the right vet to help you and your pet at this most sensitive time.

Suggested questions:

• Can I give my pet something at home, before our appointment, that will help with her anxiety about entering the clinic?

• Do you usually sedate dogs before euthanasia? If so, with what?

• What is your protocol for euthanasia?

• What drug or drugs do you use?

• How do you administer these drugs?

• I want to be with my pet the entire time; is that okay?

• What should I be prepared for?

• Will I have time to stay with my pet?

Things to listen for in the veterinarian’s answers:

• “Pat” answers that indicate a rigid protocol, such as, “We always use this drug; it’s the best one.”

• An ideal response would be, “We will access the condition of your pet on the day of euthanasia and then we’ll decide on the appropriate drugs at that time.”

• Patience and compassion, for your pet and you: Did it seem that the veterinarian really listened to your questions, or did you feel rushed?

If you don’t feel completely comfortable with the answers or conversation, it would be wise to look for another veterinarian.

Be advised that in some areas, there are practitioners who specialize in hospice and end-of-life care; also, many house-call veterinarians report that home euthanasia is a large part of their practice. One directory of these practitioners can be found at Lap of Love.

If one of these specialists is available in your area and you can afford it (they may charge considerably more than a general practitioner would for euthanizing your pet), I’d highly recommend their services. I have found veterinarians who do home euthanasia to be deeply caring and compassionate; most vets who offer this service do so out of a strong desire to offer a highly personalized, unrushed experience.

Until my most recent experiences, all of my pets have been euthanized at home. I would have gladly paid any price for this service, but there aren’t any of these practitioners where I live now.

Trust Your Gut

I teach my dog-training clients to listen to their gut when choosing a vet, groomer, trainer, or boarding facility; if something doesn’t feel right, I tell them, you must be prepared to walk out the door and find a more appropriate person for your beloved pet.

But I have to acknowledge how difficult it is to do this when you are emotionally vulnerable and bracing oneself for something as upsetting as euthanasia. I spent days before each appointment preparing for the fateful day of letting these beloved pets be free of their suffering; even when things happened that I was unhappy about, I didn’t stop the procedure and decline to go through with it at that time.

I wish I had the presence of mind to stop the procedure when I noticed that the vet didn’t touch or greet either one of my animal companions before injecting the sedative. I should have walked out the door right then and there.

Trust me: You don’t want your last memory of your dog to be him screaming in pain and panic. My friends suffered and all I can do today is help educate as many people as I can in their honor.

Trainer Jill Breitner has been training dogs since 1978 and is a body language expert. She is the developer of the Dog Decoder smartphone app, which helps people identify and “de-code” their dogs’ body language for a better understanding. She is also a certified Fear Free Professional and certified in Animal Behavior and Welfare. She lives on the west coast and uses Skype for dog training consultations all over the world.