[Updated August 24, 2018]

Vet visits can be stressful for the beings on both ends of the leash! As my dog sits in the waiting room, awash in trepidation, I, too, am often worried about what decisions I’ll need to make regarding diagnostic testing, what it’s all going to cost, and the pros and cons of every possible scenario – all while battling an overall concern for my dog’s physical and emotional health.

Veterinary care is a necessary part of responsible dog ownership, and, fortunately, a little pro-active planning and thoughtful training can help reduce vet-related anxiety for both dogs and their owners. The following tips will help prepare you and your dog for your next trip to the vet’s office.

1. Research your ideal veterinary care for your dog.

Do you have strong opinions about certain facets of animal care? Do you believe in feeding a raw diet or waiting until a certain age to spay or neuter? Do you prefer exploring holistic heathcare modalities in place of more conventional Western medicine approaches? Where do you stand on vaccinations? How do you feel about chemical flea and tick preventatives?

While the ability to use Google does not make you an expert, it’s perfectly fine to have strong preferences for how you want to address your dog’s healthcare needs. There’s space in this world for many opinions! That said, it’s wise to work with a vet who shares (or at the very least respects) yours.

Stephanie Colman

When looking for a veterinarian, ask local dog-owning friends which veterinarian they use and how well they like both the vet and the practice in general. If you’re new to the area and can’t rely on personal referrals, consider using the American Animal Hospital Association’s accredited hospital locator search tool to begin your search.

When considering a certain veterinary hospital, calling the office or viewing the practice’s website can answer questions such as where the staff refers its critical care or after-hours cases, whether or not the office is staffed overnight, or if the doctors are available on call. These are all good things to know early on when developing a relationship with your vet.

Office staff likely won’t be able to speak in detail about an individual doctor’s philosophies and approaches to care, nor will the doctor have time to field a lengthy interview call, but you can schedule a basic exam visit to serve as your chance to get your general questions answered, while allowing you the opportunity to experience the vet’s bedside manner.

AAHA Veterinary Accreditation

The American Animal Hospital Association is the only accrediting body for companion animal hospitals in the United States and Canada.

“Accreditation is voluntary. The hospitals are inviting AAHA in to evaluate how they practice,” says Heather Loenser, DVM, veterinary advisor of professional and public affairs for the American Animal Hospital Association. “Vets don’t have to do this. That’s why accreditation is a big deal, because you know you’re going to a practice where the staff wants to be excellent and wants external feedback from leaders in the field.”

When a veterinary practice applies for accreditation, the practice is evaluated on approximately 900 standards of veterinary care, ranging from pain management, infectious disease protocols and anesthesia safety to customer service procedures and how medical records are maintained. Facilities are re-evaluated every three years and must pass each time in order to maintain accreditation. The AAHA estimates that about 12 to 15 percent of veterinary practices throughout the United States and Canada are accredited.

“You can still practice excellent medicine and not be accredited, but I think pet owners will notice a difference in team work, pride and high morale of the staff in an accredited hospital,” Dr. Loenser says. “The veterinary teams who want to go through accreditation tend to hold themselves to a higher standard – they’re often the Type A of the Type A kind of people.”

For more information, visit www.aaha.org.

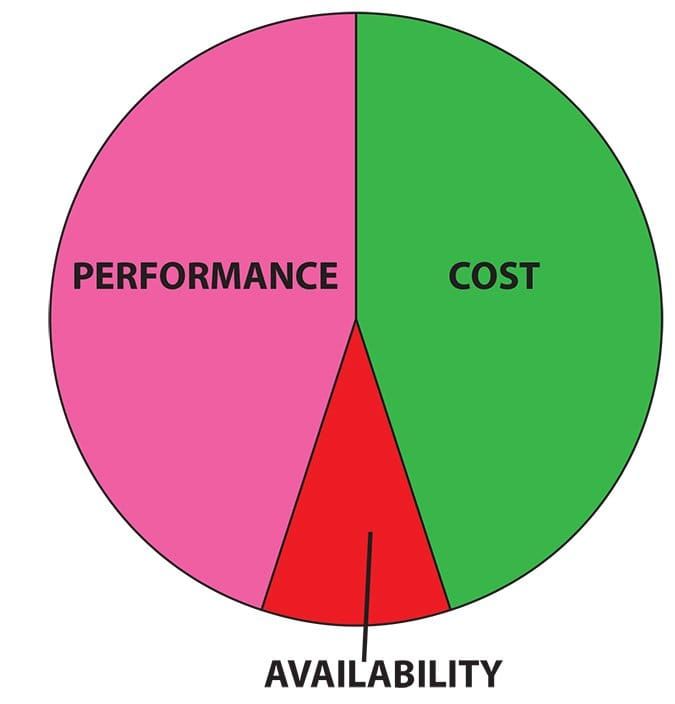

2. Plan for the cost of your dog’s veterinary care.

Nobody likes to be hit with an unexpected vet bill, but accidents and illnesses happen, and it’s important to be prepared. Pet insurance can be a great way to ease the financial sting of costly vet bills. Today’s pet insurance market is broad enough to offer a variety of coverage levels, ranging from plans designed to cover major emergencies with relatively high deductibles and lower monthly premiums, to more comprehensive plans including wellness coverage and lower deductibles, but with higher monthly premiums. Like any insurance, pet insurance can feel like a gamble. We hope we never need to use it, and when we don’t, we might grumble a little when paying the premium. At the same time, it’s a relatively inexpensive way to secure the peace of mind that comes with knowing you are better prepared, financially, to provide for your pet’s medical needs.

If insurance doesn’t feel like the right choice for your family, consider establishing and funding a separate savings account specifically for your pet’s unexpected medical issues. There’s also CareCredit, a credit card designed specifically for heath care financing, which offers 0 percent interest for 6-24 months on an initial medical charge of at least $200. (Even with pet insurance, I’ve personally used CareCredit several times.) Be warned: If you exceed the promotional period, CareCredit carries a whopping 26.99 percent interest rate.

3. Don’t wait until your dog’s minor illness or injury becomes a major one.

To go or not to go to the vet can be a stressful decision. The stress rate skyrockets after normal business hours when your regular vet is closed and you’re considering the nearest emergency facility.

It can be tempting to take a wait-and-see approach to seemingly minor medical issues. This isn’t always a bad choice, especially when you’re familiar with what’s normal for your dog, and in a position to closely monitor him for changes. Generally speaking, I don’t rush my dog to the vet the first time he vomits, has an episode of diarrhea, or seems somewhat lethargic; I’ll keep an eye on him and watch for other potential problems.

However, not all vomiting, diarrhea, and lethargy are created equal; it’s important to pay attention to the big picture. Vomiting and lack of appetite in an otherwise alert, bright-spirited dog could indicate nothing more than his body attempting to rid itself of a dietary indiscretion. Vomiting along with drooling, panting, and general restlessness is a classic sign of bloat, which is an immediate veterinary emergency.

It’s one thing to feel confident in your ability to manage minor issues that crop up after hours in an effort to avoid the higher cost of emergency care. Good old-fashioned pragmatism definitely has its merits. But the truth is, waiting often makes things worse; for example, taking a “wait and see” approach with a dog’s limp, thinking it is due to a soft-tissue injury, when the limp actually resulted from a slipped disc, can result in a drastically worsened injury. By the time you realize it’s not getting better, a dog in this situation could be facing paralysis and you’d be facing a much higher vet bill.

4. Familiarize your dog with the veterinarian’s office before your next appointment.

If your dog visits the vet’s office only when he has an appointment, there’s a much stronger chance he’ll log the experience in the “Bad Stuff!” category, even if you’re lucky enough to mostly only need routine wellness visits. (I mean, have you seen where they often put the thermometer?)

The floor is slippery, everything smells different, and you sometimes hear distressed animals vocalizing in exam rooms or crating areas. Plus, the “strangers” in the vet’s office don’t want to just to pet your dog – they often need to physically restrain or hold her in position during an exam or procedure. This can be frighteningly invasive for even the most easygoing dog during the best-case scenario. Factor in not feeling well or being in pain, and it’s no wonder why many dogs hit the brakes in reluctance as you attempt to walk into the office. Unfortunately, this fear often builds on itself over time, causing some dogs to progress from being mildly concerned to extremely anxious, or even completely panicked during a visit.

A simple way to help prevent or reduce vet-related anxiety is to visit the office when your dog doesn’t have a medical reason to be there.

Pay attention to where the visit first starts to seem scary for your dog and start there. If his nerves flare up during the walk from the car to the front door, hang out in the parking lot, offer delicious treats, play a game of tug if your dog likes toys and then hop back in the car without ever going into the office.

If he’s fine until you reach the doorway, plan your party for the area just outside of the office, being careful to stay out of the way of clients coming in and out. After a short fun-fest, return to the car, where you can either wait a few minutes and go play again, or simply drive home, depending on your schedule.

Veterinarian waiting room jitters

If your dog’s behavior tells you it’s the waiting room and beyond that trigger his nervous tendencies, happily engage your dog as you walk from the parking lot to the reception area. Offer “freebie treats” in support of your dog’s positive attitude (to further strengthen your dog’s association with the parking lot as a safe place) and ask for simple behaviors along the way.

I typically ask for (and reward) several “sits,” a hand-touch or two, and a few “spins” just on the short walk from the car to the front door as I head into the office with my dog, Saber. The more I can keep him using his thinking brain, the less likely he is to succumb to the overwhelming feelings of his emotional brain.

Once inside the waiting room, allow your dog to investigate, so long as his activity doesn’t interfere with other clients. I like to alternate between allowing my dog to look around and asking for simple behaviors, as his ability to focus on my requests tells me a lot about his emotional state. If he’s unable to focus on my requested task, he’s telling me he needs more time to acclimate. The same applies to dogs who generally enjoy treats, but who might refuse them in the waiting room.

Note: If your dog refuses food for more than a few minutes, he’s likely too far over threshold, and you should start at an easier level – just outside of the office or in the parking lot.

Invite your dog to hop on the scale to be weighed. It’s important that your dog cooperate with being weighed, since medication dosages are calculated by weight. When getting weighed requires physical restraint, the greater the risk of an inaccurate reading.

Have a seat and simulate waiting to be called for your appointment. Offer treats, calm petting and praise throughout the experience. If your dog is at all hesitant, it’s wise to end the visit here, and repeat the experience on another day. If he’s handling the waiting room in stride, and the staff isn’t super busy, ask a vet tech or member of the office staff to offer your dog treats (only if your dog is comfortable with strangers). They might even be willing to escort you to an exam room where you can continue your “just for fun” visit against the backdrop of a more formal appointment. Feed a few more treats, ask for a simple behavior or two, present a favorite toy, then cheerfully exit, remembering to thank the staff for their help.

When planning your social visits, it’s helpful to call ahead so the staff knows what to expect when you arrive, and to make sure you don’t walk into an exceptionally crowded office.

Social visits are a wonderful way to help a puppy or young dog create a positive association with the vet’s office as well as help counter any negative emotional baggage following an especially unpleasant vet visit. Taking the time to plan emotional training sessions away from necessary visits can help reduce stress levels in adult dogs, too.

Admittedly, this isn’t always the most convenient training session, since it requires travelling to the vet’s office, but as responsible, compassionate dog owners, we owe it to our canine friends to look after not just their physical health, but their emotional health and well being, too.

5. Teach your dog calm acceptance of being handled and restrained.

So much of what goes into a vet examination or medical procedure can be made easier for your dog when he’s familiar and comfortable being handled in myriad ways. Make it a habit to touch your dog all over his body as part of your everyday affection and relaxation routine. Rub his belly. Massage his leg muscles. Gently play with the inner and outer part of his ears. Massage his feet. Run your hand from atop his head toward his muzzle.

Handling your dog in this way helps normalize the experience of being touched, which can help make handling in other circumstances, like at the vet or groomer, less concerning. It’s also a great way to familiarize yourself with your dog’s topography so you’re more likely to notice a change, such as the development of or change in a lump or the sudden appearance of a rash or other skin irritation.

Pair certain types of handling with treats to help your dog build a positive association with those experiences. This is helpful for dogs who have an demonstrable aversion to being touched certain ways, as well as dogs who appear fine with the handling when at home with their owners. Taking the time to pair handling with treats, even with cooperative dogs, helps ensure against the normally “fine” behavior degrading and becoming an issue when the dog is distressed. It’s one thing to be “fine” with having your feet handled by your owners, in the safety and security of your own home. It’s a whole different story when you’re being held by strangers, in an unfamiliar place, and are in pain from an injury.

When using food to create a positive association with different types of handling, ideally you present the handling in a way that prevents the dog from feeling uncomfortable and then present the treat, rather than feeding treats simultaneous with the handling. For example, if a dog is uncomfortable with having his feet held, you might start by touching the top of one foot with two fingers, for one second, and then feed the treat. This helps make sure the dog is associating the act of being touched with earning the cookie. When feeding simultaneously, it’s easy for the presence of the food to override the handling you’re teaching the dog to enjoy. (That said, choosing to feed treats throughout an event your dog might find unpleasant is a perfectly valid way to manage the situation, in hopes of minimizing the potential for negative emotional baggage.) Slowly build toward the finished behavior, increasing your effort only when the dog can calmly tolerate the easier step.

When it comes to paw handling, it’s well worth taking the time to teach your dog to comfortably cooperate, as many vet experiences include needing to hold a dog’s feet – from the obvious such as nail trimming and foot injuries, to the less obvious, but common need to hold a dog’s paw during blood draws and when inserting IV catheters.

It’s also important to teach your dog to enjoy handling by other people. If he’s already comfortable being handled, or once you’ve desensitized him to being touched in any tricky spots, instruct your friends on where and how to handle him as you supply treats at the correct time. This will help generalize the behavior to other people.

In-office handling also often requires restraint. Teach your dog to be comfortable when you lean slightly over and into him, holding him tight to your body. Practice securing your dog’s head. When training, always start with super-short trials of just a few seconds, at a level that doesn’t appear to cause concern, followed by the delivery of a treat.

Even if your dog lets you do all of these things, there’s still value in taking time to build strong, positive associations through further training to ensure against behavior degradation during difficult times. Think of the training time as a way to help inoculate your dog against future stress!

If your dog has handling issues, or if you want to be extra prepared, teach your dog to wear a comfortable muzzle. Even the most accepting dog is apt to struggle if a foreign object is suddenly thrust upon him.

Strengthen your dog’s basic cues.

Finally, don’t underestimate the value of basic skills such as a solid “sit,” “down,” and “stand,” and the ability to relax on his side (whether you call it “chill” or “play dead”) as ways to control your dog’s body. A nose-bump hand target or duration target behavior is another great way to cooperatively guide your dog into position during an exam. The better your dog is at responding to basic cues in the vet’s office, the less he will need to be physically manipulated throughout the visit.

When working on vet-related issues, it’s important to remember behavior is fluid. It’s not uncommon to take three steps forward, then two steps backward, especially following a challenging vet visit. The good news is, once initial progress has been made, that foundation work often makes it easier to recoup benefits via additional training, even following a setback.

SUCCESSFUL VET VISITS: OVERVIEW

1. Find a veterinarian with whom you agree on issues that are important to you regarding your dog’s care.

2. Have a financial plan for unexpected veterinary expenses.

3. Protect your dog from unnecessary added stress by teaching him to comfortably accept handling common to vet visits.

Stephanie Colman is a writer and dog trainer in Southern California.