It was a beautiful fall day, and I was at a dog show. In the ring was a gorgeous veteran Greyhound – strutting his stuff in one of those peacock moments that transport gray-faced show dogs back to their youthful selves, with nothing but time and promise before them. A short time later, I heard a commotion from the parking area, and then the awful news: The handsome old dog was bloating.

Thankfully, this was a group of highly experienced dog people, and the dog’s handler immediately ran to her van to procure the bloat kit that she always traveled with. As several people helped hold the dog, she inserted a tube down his esophagus to help expel the trapped gas that was causing his ribs to expand like barrel hoops, taped the tube in place, and sped off to the nearest emergency vet. I heard through the grapevine later that the dog had, mercifully, survived.

There’s good reason why veterinarians call bloat “the mother of all emergencies.” It can come on suddenly and, if left untreated for only a handful of hours, can spell a death sentence for a dog.

Symptoms of bloat, which is incredibly painful for the dog, include pacing and restlessness; a distended abdomen; turning to look at or bite at the flank area; rapid, shallow breathing; retching without actually vomiting up any food, and excessive drooling.

Bloat is a two-part disorder, telegraphed by its formal name: gastric dilatation and volvulus. The first part, gastric dilatation, refers to an expansion of the stomach due to the presence of gas and/or food. The second part, volvulus, is the fatal blow: The distended stomach begins to twist, cutting off the blood supply and causing its tissue to die off. As if that wasn’t trouble enough, the enlarged stomach may press on the blood vessels that transport blood back to the heart, slowing circulation, creating cardiac arrhythmia, and sending the dog into shock.

Once the stomach has torsioned, emergency surgery is required to restore it to its normal position, and to evaluate whether so much tissue has died off that the dog has any hope of surviving.

This was precisely the scenario that the quick-thinking Greyhound handler had sought to avoid: By inserting the bloat tube down the esophagus and into the stomach, she not only created an avenue of escape for the trapped stomach gases, but also ensured that the stomach could not twist while the tube was inserted. As you can imagine, this is not something that most dogs entertain willingly, and, indeed, on the ride to the veterinarian, the dog struggled and the tube was dislodged. Still, it bought enough time for his survival.

Many owners, however, don’t have the inclination or the fortitude to stick a tube down their dog’s throat, even if he is bloating. And for those who have breeds that are at a higher risk for bloat, the constant stress of worrying “Will she bloat?” after each meal is enough to prompt them to consider gastropexy, a preventive surgical procedure where the stomach is sutured to the body wall. While gastropexy won’t prevent a dog from dilating, it does greatly reduce the likelihood that the stomach will flip – which is the life-threatening “volvulus” part of gastric dilatation and volvulus.

Dog Bloat Risk Factors

Owners who are determined to prevent bloat nonetheless want to understand its causes before submitting their dogs to an elective surgery like gastropexy. The problem is, veterinary science is still unclear about precisely what triggers an episode, and instead can only offer a long and varied list of risk factors.

The mother of all bloat studies was done two decades ago by Dr. Lawrence T. Glickman and his colleagues at the Purdue University Research Group, and is still being discussed and quoted today. The 1996 study and its follow-up research found that many food-management practices that were initially believed to help reduce the risk of bloat – like feeding from a raised food bowl, moistening dry food before serving, and restricting water access before and after meals – actually increased the odds of a dog bloating.

Other risk factors include eating only one meal a day; having a close family member with a history of bloat; having a nervous or aggressive temperament; eating quickly; being thin or underweight; eating a dry-food diet with animal fat listed in the first four ingredients, and/or eating a moistened dog food, particularly with citric acid as a preservative.

Not surprisingly, certain breeds were found to be at high risk for bloat, particularly large or giant breeds. Topping the list were Great Danes, followed by St. Bernards and Weimaraners. The study found that breeds with deep and narrow chests – like the Greyhound that started this story – are also at higher risk for bloating, as are males and older dogs.

Also according to the Purdue study, the risk of bloat was more than twice as high in dogs seven to 10 years old compared to dogs two to four years old, and more than three times as high in dogs age 10 and older.

Reducing the Risk of Bloat

While not a guarantee that your dog will avoid experiencing an episode of bloat, these steps can help lower the risk.

1. Feed several smaller meals per day.

Feeding a large, once-a-day meal can extend the stomach and stretch the hepatogastric ligament, which keeps the stomach positioned in the abdominal cavity. Dogs that have bloated have been found to have longer ligaments, perhaps due to overstretching.

2. Slow down fast eaters.

Some theories suggest that air gulping can trigger bloat. To keep your dog from gobbling down his meals, invest in a slow-feeder bowl, which has compartments or grooves to require dogs to pace themselves; there are several brands available. For a low-tech version, try placing a large rock in the middle of your dog’s food bowl, which will force him to eat around it. (Of course, make sure the rock is large enough so it can’t be swallowed.)

3. If you feed kibble, add some variety.

Dogs that are fed canned food or table scraps have a lower incidence of bloat. If you feed kibble, try to avoid food with smaller-sized pieces, and opt for brands that have larger-sized pieces. While some raw feeders maintain that feeding a raw diet prevents bloat, there are no studies to support this, and raw-fed dogs are not immune to bloating.

4. Don’t go for lean and mean.

Studies show that thinner dogs are at greater risk for bloat; in fatter dogs, the extra fat takes up space in the abdomen and doesn’t give the stomach much room to move. While no one is advocating that you make your dog obese, keeping a bloat-prone dog on the slightly chunkier side might have some merit.

5. Reduce your dog’s stress.

Easier said than done, of course. But if at all possible, opt for a house sitter instead of taking your dog to a kennel. If you have multiple dogs, feed your bloat-prone dog separately, to avoid the stress (and resultant gulping) from worrying that his meal might be snagged by a housemate.

6. Don’t eat and run.

Veterinary experts recommend that you avoid giving your dog hard exercise one hour before and two hours after he eats. Many give the green light to walking, however, as it does not jostle the full stomach and in fact can help stimulate digestion.

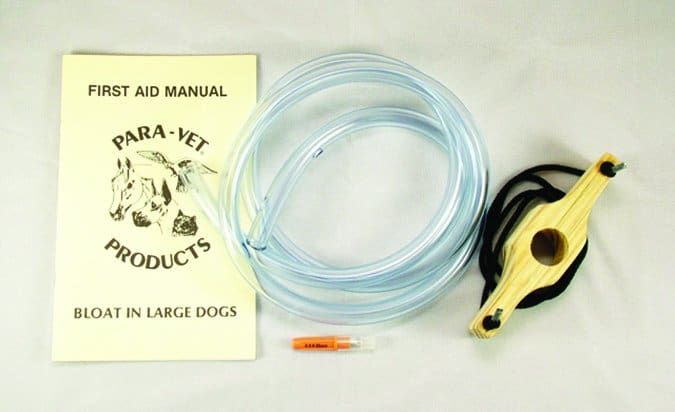

Assembling a Bloat Kit

Because bloat strikes when you least expect it – often at night, when most veterinary practices are closed, and the nearest emergency vet might be a distance away – a bloat kit can be a literal lifesaver.

Some dog-care sites sell pre-assembled bloat kits. (One option is available from A Better Way Pet Care.) Most include clear vinyl tubing (the kind sold by aquarium stores); a wooden mouth block, to keep the mouth open while the tube is being inserted (a piece of PVC pipe can work in a pinch), and water-soluble lubricant.

Ask your vet to show you how to measure the tubing so that it is the correct length, how to insert it, and how to tell if you are passing the tube down the trachea rather than the esophagus.

Remember that a gastric tube is not a treatment for bloat; it is a first-aid measure. If you are unsure of how to use the kit, or if you are alone and don’t have someone to transport you while you work on the dog, make getting to the vet your first priority.

Deciding on Surgery

If your dog bloats and her stomach has torsioned, surgery is the only recourse if you want her to survive. And if you get to the vet in time, the odds are with you: In a retrospective study of 166 cases between 1992 and 2003, researchers found that short-term mortality resulting from bloat surgery was a relatively low 16.2 percent.

Risk factors for a fatal outcome included having clinical signs more than six hours before surgery (i.e., the longer you wait, the worse your dog’s prognosis), hypotension during any time of the hospitalization, peritonitis, sepsis, and administration of blood or plasma transfusions. Dogs whose tissue damage was so advanced that they required part of their stomach or their spleen removed (partial gastrectomy or spleenectomy, respectively) also had worse prognoses.

But the decisions regarding a gastropexy – essentially, “tacking” the stomach so it cannot torsion – are not as clear-cut. If your dog has never bloated, you’ll need to weigh the risk factors: Is your dog’s breed prone to bloat? (Great Danes, for example, have a whopping 42.4 percent chance of bloating in their lifetime.) Do you know of any siblings, parents, or other close relatives who have bloated? Is your dog nervous, aggressive, or a super-fast eater?

And, most important, has your dog bloated before? Studies indicate that such dogs have a recurrence rate of more than 70 percent, and mortality rates of 80 percent.

Types of Tacks

There are several kinds of gastropexy surgery. Securing the bottom of the stomach to the right side of the body so it cannot rotate during an episode of bloat is the common goal of each type of surgery, but slightly different methods are used to accomplish this. There are no studies that compare the efficacy of the various types of gastropexy, but the general consensus is that there is not a huge difference between them. Most veterinarians will choose one over the others based on their own preference and amount of experience.

Incisional gastropexy is a straightforward procedure in which the bottom of the stomach (the antrum) is sutured to the body wall. It relies on only a few sutures until an adhesion forms.

Belt-loop gastropexy involves weaving a stomach flap through the abdominal wall. Though a relatively quick procedure, it requires more skill than an incisional gastropexy.

In a circumcostal gastropexy, a flap from the stomach is wrapped around the last rib on the right side and then secured to the stomach wall. Proponents of this approach note that the rib is a stronger and more secure anchor for the stomach. This type of gastropexy requires more time and skill to perform; risks include potential rib fracture and pneumothorax, in which air leaks into the space between the lung and chest wall.

Gastropexy is now being performed with minimally invasive approaches such as laparoscopy and endoscopy, which shorten surgery and anesthesia times, as well as the time needed for recovery. Though both use remote cameras to visualize the surgery area, the laparoscopic-assisted approach requires an extra incision through the navel, which allows the surgeon to directly visualize the position of the stomach and make any modifications necessary.

A 1996 study of eight male dogs compared those that had laparoscopic gastropexy with those that had belt-loop gastropexy, and concluded that the laparoscopic approach should be considered as a minimally invasive alternative to traditional open-surgery gastropexy.

Complications from gastropexy are relatively minor, especially for young, healthy dogs who are undergoing the surgery electively, before any incidence of bloat. As always, be sure that your dog has a complete pre-surgical work-up to ensure there are no chronic or underlying conditions that might compromise her ability to successful recover from surgery. And again, while gastropexy isn’t foolproof, Dr. Glickman has been quoted as saying that the risk of bloat and torsion after the procedure is less than five percent – not bad odds at all.

If you do elect to have a gastropexy performed on your dog, many veterinarians do the procedure at the same time as spaying or neutering. That way, the dog doesn’t have to go under anesthesia again, or, in the case of conventional surgery, be “opened up” another time.

In the end, the question of whether or not to have a gastropexy done is arguably tougher for those whose dogs who are not at very high risk: The owner of a Great Dane has a greater incentive for getting a gastropexy than, say, the owner of a Shih Tzu, whose bloat rates are not as comparably high.

A 2003 study that looked at the benefits of prophylactic gastropexy for at-risk dogs used a financial metric to assess the benefits of surgery: Working under the assumption that elective gastropexy surgeries cost about $400 and emergency bloat surgeries cost at least $1,500 – or as much as four times that – the study concluded that the procedure was cost effective when the lifetime risk of bloat with torsion was greater than or equal to 34 percent.

As with any complex decision, assess your dog’s risk factors, as well as your individual circumstances, and then make the choice that seems right for the both of you.

Denise Flaim raises 12-year-old triplets and Rhodesian Ridgebacks, on Long Island, NY.