The word “surgery,” which dates back to the ancient Greeks and Romans, literally means “hand work.” And, of course, one of the biggest ingredients for a successful outcome is the person at the other end of the scalpel: Everyone wants their dog in the hands of a knowledgeable, experienced, and competent surgeon.But there’s also a great deal that you can do to help your dog navigate her surgical procedure as smoothly and safely as possible, whether it’s a complicated orthopedic reconstruction, or a run-of-the-mill teeth cleaning.

No matter how skillful the veterinarian, surgery is an invasive procedure that puts stress on your dog and can open the door to problems if her body is not up to the challenge. The greater your lead time, the more opportunity you have to help prime her for the physical challenge ahead.

Question the Necessity of Your Dog’s Surgery

But let’s back up a second. One of the most important considerations about your dog’s impending surgery is whether it is even necessary. Obviously, if he’s had his leg shattered in a car accident or swallowed a corn cob (which is supremely indigestible, by the way – be very careful to put those buttery barbecue leftovers in a secure trash receptacle), going under the knife is likely unavoidable. But what about elective surgeries, or those that aren’t life threatening? It’s worth a little research and a second opinion to determine if there is a less invasive way to deal with the problem.

Consider, for example, a dog who has chronically impacted and infected anal sacs. These glands, located on either side of the anus, secrete a potent-smelling, oily brown liquid that is usually expressed during bowel movements. But sometimes, the ducts in the glands become clogged, leading to “butt scooters” who drag their bottoms across the floor to relieve their discomfort. If infection is present, antibiotics are usually prescribed, along with warm compresses to reduce inflammation; in severe cases where an abscess has formed, the veterinarian might need to lance the area.

For many dogs, impacted or infected anal sacs are a one-time problem that resolves itself with time and treatment, and never recurs. But in dogs for whom this is a chronic problem, removal of the anal sacs is often recommended.

This surgery – formally called an anal sacculectomy – is not without its risks, one of which is permanent incontinence. But when anal-sac infections are a constant and seemingly intractable problem, what’s an owner to do?

Diet modification is one possibility. Many owners have reported that a switch to a raw-food diet has cleared up their dogs’ persistent anal-sac woes. Because of their high bone content, the stools of raw-fed dogs are very hard, and they naturally express the anal sacs, arguably much more effectively than the cooked “high fiber” diets that are often recommended for this problem.

Holistic veterinarian Christina Chambreau of Sparks, Maryland, adds torn cruciate ligaments to the list of issues that don’t necessarily have to be solved with surgery. “All that most conventional veterinarians can offer are braces, surgery, or just letting the dog limp,” she says. “There are multiple holistic approaches that can resolve stretched cruciate ligaments and sometimes resolve even completely torn ones.”

Dentistry is another area where she suggests a fresh look; ask your veterinarian if there is an acceptable alternative to putting your dog under for a regular cleaning. If anesthesia is unavoidable, though, don’t fret. “Many people are really afraid of anesthesia in their older dogs, though anesthesia is now so safe, other than the odd reaction, that most animals will do fine regardless of their age,” Dr. Chambreau says.

Some common elective surgeries can benefit from you taking a step back and reassessing the best timing for your dog. For example, attitudes about the appropriate time for spaying and neutering have evolved in recent years. Once routinely and reflexively done at six months of age, desexing is now sometimes performed much later, allowing the dog to mature physically before shutting off the hormonal spigot. Do your research to make sure you are comfortable with the timing your veterinarian is recommending. See “Risks and Benefits of Spaying/Neutering Your Dog,” (February 2013), for more information about the timing of spay/neuter surgery.

The bottom line: In cases where surgery is elective, or at least not an emergency, take a moment to research whether there is a less invasive, gentler way of dealing with the problem. Often, an appointment with a holistic veterinarian is invaluable in this regard.

Preparing A Dog for Surgery

Most dog owners know the basics of prepping their dog in the days before surgery: Withhold food and water 12 to 24 hours beforehand, depending on your vet’s instructions, to ensure that the stomach is empty and there is no risk of your dog vomiting during the procedure.

Inform your veterinarian of any medications or supplements that you give your dog, and follow directions about if and when to discontinue them. Some herbs and neutraceuticals, such as Ginkgo biloba and Vitamin E, can thin the blood and increase bleeding, which are definitely no-nos with an impending surgery. Still others, such as large doses of Vitamin C, may interfere with anesthesia – another risk you want to avoid.

Expect that your veterinarian will order a pre-operative blood panel (see “Get Your Dog’s Bloodwork,” March 2015) to make sure that there is no underlying condition that could compromise your dog’s ability to withstand the physical stress of surgery. If your veterinarian notices any other medical values that are “off,” she might require further screening. For example, a heart murmur in an older dog could be a compelling reason to do an echocardiogram, to rule out congestive heart failure, heartworm infection, or a structural problem in the heart.

Board-certified veterinary surgeon Tomas Infernuso of Veterinary Traveling Surgical Services in Locust Valley, New York, says one of the biggest problems with surgery is the risk of contamination. Virtually everything in the hospital environment – the veterinary staff, the surgical instruments, your dog’s skin, even the air in the room – can transmit bacteria into your dog’s body. For this reason, many veterinarians administer antibiotics as a precaution before, during, and sometimes for a period after the surgery. With all these external agents for transmitting infection, the last thing your dog needs is a threat from within.

“If your dog has an infection, like a urinary-tract infection, you need to make sure you take care of that before the surgery, or you risk spreading it,” Dr. Infernuso cautions. Similarly, he will postpone surgery if a dog has untreated periodontal disease, because of concerns about bacteremia, or bacteria in the blood. “Bacteria from the oral cavity can spread to the bloodstream,” he explains. “Many of these patients have a low grade of sepsis, which can potentially turn into a high grade.”

Another less obvious risk for a dog headed for surgery is a close haircut. If you’re someone who does a “shave down” of your long-coated dog during the hot summer months (even though most experts say you shouldn’t – see “How to Prevent Heat Stroke in Dogs,” July 2015), think again. Trimming a dog’s fur isn’t an issue; it’s shaving that gets down to the skin that is contraindicated before surgery.

“When you shave a dog, it can create a lot of abrasion on the skin,” Dr. Infernuso explains. “That can allow staph bacteria to go from the skin into the bloodstream.”

Clean and Ready

Good grooming doesn’t just make your dog look more appealing: It can also make recovery safer for him, especially if his nails are too long; they’ll make it that much easier for him to scratch at and dislodge stitches. You can ask for your dog’s nails to be clipped while he is under anesthesia, though if they are really long, they won’t be able to shorten them enough in one session to prevent your dog from using them to damage an incision. If you have a few weeks before the surgery, you’ll likely be more successful doing them yourself. If you grind them with a hand-held rotary tool like the Dremel, you can plan a manicure every three to four days. When you are drilling away, work all around the nail, including the sides, which will prompt the quick to recede that much faster.

If your dog hasn’t had a bath in a while, consider bathing her the day before surgery, as you likely won’t be able to drench her in water for some time after the surgery. Be on the lookout for fleas. They must be dealt with before your dog goes under the knife; you don’t want your dog itching and scratching and chewing herself as she recovers.

Many dogs will be required to wear a cone or Elizabethan collar after surgery, to prevent them from reaching and worrying the surgery site. If your dog is not happy wearing one – or has never worn one before – get her used to wearing it. In the weeks leading up to the surgery, have her wear it for a few minutes each day, gradually leaving it on for longer and longer periods. Instead of the traditional hard-plastic cone, which can impede your dog’s mobility, not to mention scratch up all your wood furniture, check out the soft fabric collars that are available. Test one out to see if it can hold up to your dog’s contortions.

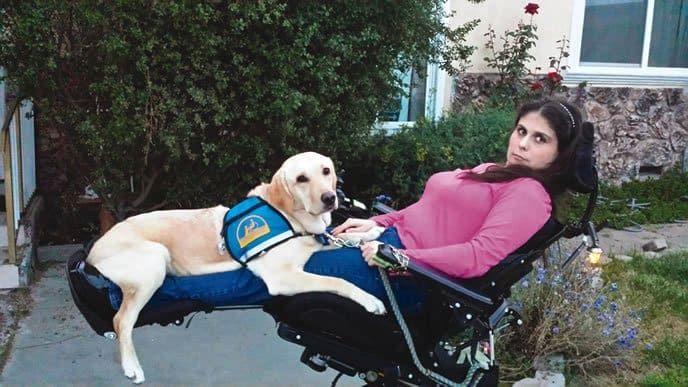

Think ahead to the accommodations your dog will need once she gets home: If her wound will be draining, make sure you have plenty of fresh, clean bedding on hand; keep clean sheets covering her freshly washed dog bed. If she’s going to be limping, or hobbling around on three legs, make sure there is a non-slip, easily navigable path to her potty spot. If she’s a large dog, look into ways to give her some support or guidance as she’s walking, either by making a sling out of a king-sized pillowcase or twin sheet to pass under her body, or investing in a support harness that lets you maneuver and guide your dog when she’s less than steady on her feet.

Finally, fat dogs are at a greater risk for surgical complications, including poor recovery from anesthesia. “A lot of these patients are diabetic, or have Cushing’s disease,” explains Dr. Infernuso, adding that the high levels of glucose in their systems can make them susceptible to post-operative infections and slow healing. And once they go home from the hospital, their extra padding can undo any benefits of the surgery. Excess pounds amplify the impact on the dog’s joints; for example, if you dog went in for a knee surgery, putting all his excess weight in the other side might cause that knee to blow out, too, leaving him literally without a leg to stand on. Keeping your dog slim should be a priority at any time, but in the weeks or months before a planned surgery, achieving even a little weight loss would be beneficial. See “Keeping Your Dog Thin is a Lifesaver,” January 2014, and “Helping Your Dog Lose Weight,” September 2009.

Emotional Rescue

While ensuring your dog is in peak physical condition before surgery is optimal, his emotional state is just as important.

If you have some lead time, start working on desensitizing your dog to visiting the veterinary clinic, so the day of surgery isn’t as traumatic for him. Ideally, pop into your vet’s office daily – or as often as you can manage it – just for a quick hello and a windfall of treats. The idea, of course, is for your dog to associate the vet clinic as a place where Good Things Happen.

Dr. Chambreau advises scheduling extra time in the two or three weeks before surgery to do what your dog loves. That might be some games of fetch (if his physical condition permits) or visits to the dog park when his favorite regulars are there.

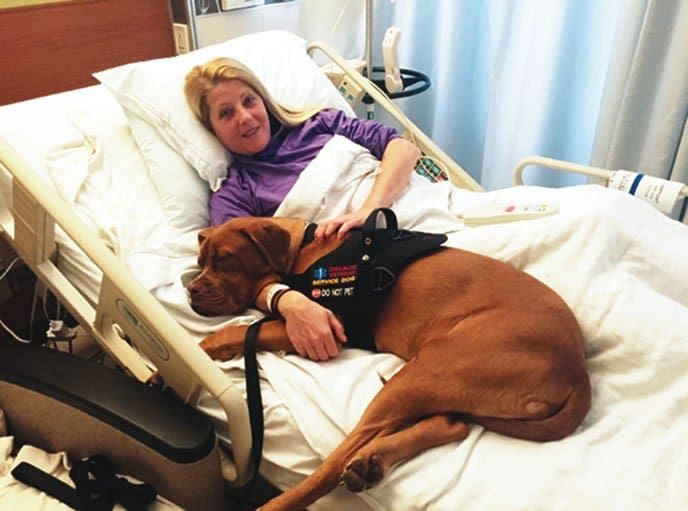

“If your dog’s a cuddler, then make sure she’s getting the extra attention she wants,” she says. This isn’t just feel-good indulgence; tending to your dog’s emotional well-being will boost her endorphins and other beneficial hormones, translating into an elevate state of physical wellness as well.

This is a good time to employ any safe and gentle holistic practices you are familiar with to calm, center, or balance your dog, such as reiki, quantum touch, reconnective healing, flower essence remedies, aromatherapy, TTouch, or massage.

And don’t forget to calm and center yourself! After all, waiting for your dog to get out of surgery and to receive the veterinary surgeon’s report can feel like an eternity.