By Randy Kidd, DVM, PhD Pain may be the most enigmatic of all the disease symptoms of man or beast. It is a sensation we all have experienced at one time or another and in varying degrees. But, few of us can explain adequately how a particular pain feels, fewer still can give a reasonable explanation for why pain occurs; and despite all the recent scientific research that has gone into pain, we still have a minimal understanding for how it occurs – or truthfully, for how to consistently prevent or alleviate it. Now, couple all this with the fact that we are dealing with pain in an animal who can’t talk to us, who can’t tell us where or when or how it hurts, and we have further compounded the entire equation.

At its essence, pain is a language that says something is wrong. Ordinary or acute pain is a barometer of tissue health; much like an automobile’s warning system, it raises an alarm whenever something has penetrated the protective shield. Pain is a daily reminder that we and our best buddies are little more than a fragile collection of cells and fluids that can easily be pierced, burned, torn, or broken. Pain sensors occur in most organs of the body – from bone to skin, from nose to tail, and from the gut to the muscles, tendons, and ligaments. Some areas of the body are highly innervated with pain sensors – the areas around joints, for example, and areas that surround vital organs. Other areas, such as a dog’s foot pads, are relatively free of pain sensors. Anatomy of pain Nearly all areas of the body are supplied with pain receptors – actually, sensory neurons. These neurons are activated by inputs that are often very specific for the receptor involved – receptors geared to respond to cold, heat, or tissue damage, for example. Some receptors are more attuned to feeling somatic pain that originates on the skin or deeper in the musculoskeletal system. Other receptors respond to visceral pains that result from inflammation, compression, or stretching of the chest, abdominal, or pelvic viscera. Pain scientists have further defined pain receptors as being nociceptive (pain caused by an injury to body tissues), neuropathic (from abnormalities in nervous system), and psychogenic (pain that is related to emotional or psychogenic concerns). The important part of all this is to understand that there are many kinds of pain; each kind of pain feels different; and each kind of pain will require a slightly different form of therapy. After one or more of the pain receptors have been stimulated, the resulting sensation travels to the spinal cord where the pain messages release chemicals (neurotransmitters). These neurotransmitters activate other nerve cells in the spinal cord, which then processes the information and transmits it up to the brain. Not all pain messages reach the brain. Some are filtered at the level of the spinal cord where they encounter specialized nerve cells, called “gate keepers.” Strong pain messages, such as when an animal touches a hot stove, open the “gate” to wide open, letting the message take an express route to the brain. Weak pain messages, however, such as from a minor scratch, may be filtered out or blocked by the gate. We can affect the gate by altering the messages on the nerve fibers that transmit touch. For example, rubbing or heat decreases the transmission of pain signals. In addition, some of the pain killers, natural and otherwise, work by altering the way the gate opens or filters painful stimuli. Pain messages can also be intensified in the spinal cord where certain nerve cells can act to “wind up” or “sensitize” the pain input so it has more impact on the brain. A recent injury creates an area of hypersensitivity in the area surrounding the trauma that helps to transmit a heightened pain perception to the brain; perhaps this acts as a protective mechanism that tells the body to try to prevent any further damage from occurring at the site of the trauma. At the same time that all of this modulation of pain is going on, the instigator of the pain (a splinter, for example) may be causing local inflammation, and the products of inflammation cause more pain and swelling. Examples of inflammatory agents include bradykinin, several of the prostaglandins, and at least one of the enzymes that synthesize prostaglandins, cyclooxygenase 2 (Cox-2). The pain and swelling of inflammation may also act as a protective mechanism by isolating the injury, and the increased blood flow to the area speeds healing. Once the pain message reaches the brain, it interacts with nerve cells there, and these reactions can either subdue the pain or ratchet up the animal’s perception of the pain. There are numerous sites in the brain where pain is processed, including the reticular formation (which is responsible for producing an increase in heart and respiratory rates and elevation of blood pressure), and the thalamus and cerebral cortex, where conscious awareness of pain occurs. The brain contains natural painkillers, including endorphins and enkephalins, which diminish the pain messages. But the animal’s emotional or psychological state may cause him to perceive the pain at a higher level. Consider the dog who once had a painful experience at the vet’s office. The next visit, because the dog has been anticipating more pain from the moment he walks in the door, he screams bloody murder at the mere sight of the needle. Chronic pain All the above describes acute pain; chronic pain has a slightly different pattern. Chronic pain is any pain that persists beyond the time expected for an injury or illness to heal. With chronic pain, no longer can the pain be viewed as the symptom of another disease, but as an illness unto itself. Any pain that has persisted for six months or longer is considered to be chronic. Chronic pain may cause the same sensations as acute pain – jabbing, throbbing, stinging, burning, sharp, dull, tingling, or aching. (While we can’t be certain dogs can perceive pain as we do, their reactions to it indicate that they probably do.) Further, pain may be constant or it may come and go. Chronic pain often accompanies chronic diseases such as arthritis, cancer, diabetes, or some skin conditions, but long-term pain may also stem from the aftereffects of an accident, infection, or surgery. In addition, each and every critter (including each human) has his or her personal ability to tolerate pain. There are two terms used to describe the way an individual feels and responds to pain: Pain threshold is that point where we feel the sensation of pain; pain tolerance is that point where we feel we must remove ourselves from the source of the pain. Now, while the pain threshold may be relatively constant, an individual’s ability to tolerate pain is dependent on many factors. Different pain stimuli may affect an individual in different ways. Someone who can stoically leave his hand in ice water for long periods, for example, may want to scream from the pain of a minor needle prick. And, that same person may have “good” days and “bad” days – some days he can endure needle pricks with almost no sensation; other days are his “scream at the needle” days. Dogs are exactly the same. Some are pain tolerant for one type of pain, while that same dog will go absolutely nutty over another type of pain. And as individuals, they can have their good (stoic) days and their bad (wimpy) days. No one knows quite why this happens in humans or dogs, but added emotions – fear, depression, anxiety, for example – may have something to do with a lowered pain tolerance. Further, the very concept of pain and how we and our pets deal with it is related to the culture we were reared in, our gender, environmental factors, and the pain being suffered by others nearby. Certain dog breeds are known for their stoicism under pain and others wilt at the mere thought of pain. In humans, men and women are apparently very different when it comes to pain tolerance, but this has not yet been shown in dogs. Experimental evidence from trials on mice show that brain waves of those mice that were sitting placidly in a cage nearby, closely mirror the brain waves of the mice that were in obvious pain. Empathetic pain is apparently a very real phenomenon. Dogs do associate past painful experiences with the environment where they occurred, which is why the vet’s office may not be one of their favorite places. I have found, though, that we can create a holistic and comfortable environment, even in a vet clinic where many of the dog’s previous experiences were painful. All it takes is a soft rug to sit on instead of the cold metal tabletop, and perhaps some calming aromatherapy or flower essences added to the environment. Furthermore, animals who have experienced pain relief from past acupuncture or chiropractic treatments seem to be the most calm and accepting patients I have ever seen. One more point: animals definitely react to the way their caretakers are acting, and if the caretaker seems to be overly concerned, his dog will respond in kind. Remember that emotions, even emotions of the folks or animals that are nearby, can alter pain receptors and pain pathways to make the pain seem worse. The calmer the caretaker remains, the calmer – and more pain free – the dog. Aftereffects of pain Pain does not end with the pin prick; it is one of the primary stressors within the body. Pain interacts with and affects almost all body systems: musculoskeletal, immune, hormonal, and even the arrangement of the nerves themselves. Pain disrupts normal function. A primary example here is that any pain of the muscles, joints, or bones will affect the gait and comfortable posture of the affected individual. Gastrointestinal pain may alter intestinal motility and/or the pain may change the amount or kind of digestive enzymes being supplied to the gut. And a normally balanced hormonal output can be altered by pain. Any kind of pain, even minor pain, can be disruptive to normal sleep patterns. Loss of sleep, coupled with the anxiety of not knowing what is going on with one’s body often leads to depression. While I’m not sure we can say dogs suffer from true depression as we understand it, they can certainly have the appearance of a “depressed” animal when they are in pain. Chronic pain of any segment of the musculoskeletal system may lead to compensation. Out of necessity, wild animals are particularly adept at accepting pain, learning how to compensate for this pain, and moving on so they can perform the functions (however limited these functions become) that keep them alive. Four-legged animals thus quickly learn how walk and run on three legs to avoid putting pressure on the one sore leg. This compensatory gait is beneficial early on, but if it lasts long enough, the body begins to form a fibrous (and eventually bony) protective shield that spans over the sore joint. In addition, the animal’s patterns of posture and gait will be altered, and these alterations may occur far away from the original site of pain. As an example, a dog’s sore hind leg may cause it to bend his neck to create a balance that reduces the painful pressure on the sore leg. Animal chiropractors are well aware of how compensation often affects areas of the body that are far away from the initial site of the injury, and chiropractic adjustments are often necessary at the “faraway” site as well as at the site of the injury. Recognizing pain Symptoms that may indicate your dog is in pain include: • Behavioral changes. Licking and yawning are signs that a dog is nervous. Dogs who hurt do not want to be picked up, or even be touched, so they may lick their lips or yawn whenever you or anyone else tries to approach them. Dogs in pain are typically restless. If they can move without pain – for example, after a painful surgery – they will be up and down, up and down; they pace; they can’t sleep; and they can’t seem to get comfortable in any one position.

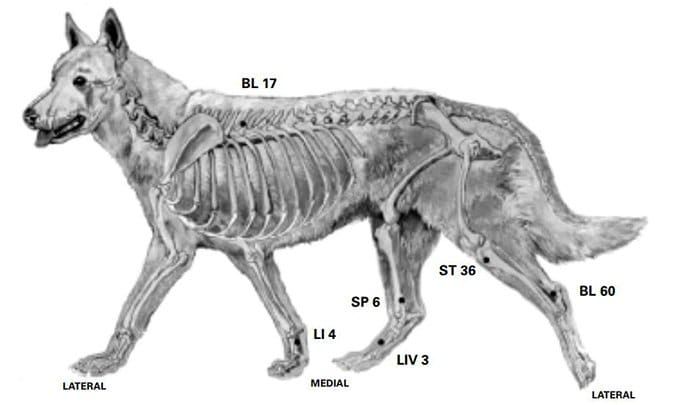

Some dogs will want to hide from any contact that might possibly hurt, and they may become aggressively grouchy to avoid that contact. Fear biting is common with dogs that hurt. Other animals may whine and want to be constantly held. All these behaviors are a result of the animal being out of control of its own body – a forerunner to becoming depressed, mentally and physically. • Abnormal gait or posture. Pain anywhere in the feet, joints, muscles, tendons, ligaments, or spinal column may cause the dog to have a noticeable limp. However, dogs are so adept at compensating for the pain (see above), it may be difficult to detect an abnormal gait pattern. Pain may also be detected by observing a stiffness or reluctance to move or rise from sleeping, or when climbing stairs or trying to jump onto the couch or bed. Pained animals may stand off center (trying to ease the pressure from the painful leg), carry their head or tail off center, or sit or lie down (or get up) only on one side of their body. Animals with hip or knee pain may “bunny hop” (a gait of the hind legs that looks like, well, like a bunny hopping), or they may “puppy sit” – a posture where they sit on their butts with hind legs extended to one side. • Vocalization. How an animal “talks” about his pain is perhaps the most variable of any of his symptoms. Some animals will not vocalize, no matter how much pain they are in. (These are the dogs we typically say have a high pain threshold. In reality, these “stoics” likely still feel the pain, but they have a high tolerance to that pain.) Other dogs tell you straight away they are in pain: whining, crying, moaning, groaning, yipping, growling, and/or howling. Again, the amount of verbal complaining you hear from the dog depends on the individual, not necessarily on the amount of pain he is experiencing. • Other pain symptoms. Animals who are experiencing abdominal pain are often reluctant to move. They may refuse to eat, and they may moan or bite at their abdomens or flanks. They may also vomit or have diarrhea. Chest pains cause shortness of breath and possibly an increased heart rate, both of which result in an inability to exercise. Some dogs don’t want to eat when they hurt. Increased heart and respiratory rates are fairly consistent symptoms of pain, but they may not be evident to the casual observer. There are two symptoms of pain (and relief from pain) that my clients have taught me over the years. One has to do with the dog’s eyes. A dog’s caretaker often notices that a dog in evident pain has “cloudy” eyes, or eyes that seem “empty,” as if there is nothing behind them. In my practice, I used chiropractic adjustments, acupuncture, herbs, and nutritional supplements, and after treatments, the caretakers would often report that their dogs’ eyes “brightened up,” that they were clearer, or seemed to have more “energy.” The other is a comment I’ve heard frequently after I had begun treatment on a canine patient: “I’ve got my dog back!” Interestingly, as a practitioner, I was not often able to see any noticeable difference in the patient; the dog might have almost the same amount of limp as when I began therapy. But, there was something about the dog that the owner recognized – something that told him that the dog was more “normal” than before. Conventional pain medicine Analgesics are medicines that are meant to relieve pain. There are three major categories of conventional medicines for pain control: local anesthetics, opioids, and non-opioids. This last category includes a large class of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), but also covers common but not fully understood drugs like acetaminophen and aspirin, which defy categorization. Local anesthetics provide pain relief by blocking pain stimuli from reaching the brain and spinal cord. They differ from the opioids and NSAIDs in that they abolish pain rather than diminish it. An example of a local anesthetic is lidocaine. The action of enkephalins and endorphins on pain receptors is the body’s intrinsic pain-suppressing system; it is the activity of these two hormones that makes the body feel good after jogging, sex, or an acupuncture treatment. Opioids (or opiates) bind to enkaphalin receptors along the pain pathways in the central nervous system, which effectively prevents the transmission of pain signals. Examples of opioids include morphine, codeine, methadone, Demerol, and Darvon. Most of the NSAIDs work by blocking the action of the pain-causing prostaglandins, and some of them achieve this by blocking the action of the prostaglandin-producing cyclooxygenase enzymes (Cox-1, 2, and 3). Examples of NSAIDs include ibuprofen and naproxen. Aspirin is considered by some to be an NSAID, but others disagree. While all these have been shown to be very effective, most of the time, there can be a tremendous variance among individuals. In fact, some of the analgesics may have an opposite effect on some individuals, actually causing more pain. In addition, each analgesic has a pretty potent list of adverse side effects. Not long ago, on an electronic bulletin board about veterinary complementary and alternative medicine, a number of veterinarians exchanged stories about their experiences with delayed healing for wounds or surgical incisions when the animal is given NSAIDs. In all cases, you will need to discuss with your veterinarian the potential risk/benefit ratio whenever you are choosing an analgesic for your dog. Natural pain relievers Fortunately, there are many alternative ways to approach pain control, and in my experience these are often not only less dangerous, they also can be more effective. As a general rule, alternative medicines take longer to act, and may not have the depth of activity that conventional medicines do. However, they are typically much safer to use, will not be addictive, and tend to have a much broader spectrum of activity – that is, they may help to relieve several kinds of pain, and they may also help alleviate some of the emotional components of pain as well as its physical aspects. Your holistic vet should be able to advise you on the best applications, dosages, and methods of use for the alternative forms of pain control. • Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM): Practitioners of TCM believe that pain is caused by a blockage of the flow of chi or “energy.” Thus when a joint hurts, for example, it is because the flow of chi is stuck there, causing pain. TCM uses acupuncture needles (and herbal remedies) to help re-create a normal flow of chi through areas of pain. In addition, acupuncture causes the release of enkephalins and endorphins, the body’s natural pain relievers. • Those who employ chiropractic believe that joints that are stuck – so that their normal range of motion has been altered – change the response of the pain receptors in the area, often causing pain. Also, a “stuck” spinal vertebrae that can’t move properly may also alter the pain messages being sent to the brain. Chiropractic adjustments are intended to restore the joint to its normal motion so that all nerve impulses are restored to normal. • I’ve had phenomenal results when using the combination of acupuncture and chiropractic for treating pain. The most dramatic results have come when treating musculoskeletal dysfunctions such as arthritis, but results when treating some deep or abdominal pains have also been very rewarding. • Homeopathy: One of the best of the natural pain medications, especially for bruises, sprains, or trauma to the eyes, is the homeopathic remedy Arnica. Hypericum, Bryonia, and Ruta are also excellent for many painful conditions. • There are several herbal remedies that have a long history of use for alleviating pain. Gastric pain may be eased with antispasmodics such as caraway, ginger, valerian, and wild yam. Willow bark contains the substance that is the active ingredient in aspirin. Herbal oats act as a nervine – a substance that balances the nervous system. Capsicum (red pepper) is an effective topical remedy for painful skin lesions, and it can be taken internally to help ease painful, arthritic joints. • Others: Supplements such as glucosamine, omega 3 and 6 fatty acids, B vitamins, inositol, and lipoic acid have proven beneficial for treating pain. It has been shown that glucosamine decreases the amount of NSAIDs needed to control pain in joint conditions, at least in humans, and it is likely that many of these supplements have similar beneficial properties. Don’t forget that there is almost always a mental or emotional component to pain, so calming herbs can be extremely helpful. Flower essence remedies are directed toward emotional distress. For example, the remedy Agrimony works well for the dog who appears to be distressed due to pain. And sometimes a calming aroma, such as lavender, wafted throughout dog’s resting places in the house, clears and calms the mind made nervous from pain. Conclusion There is evidence from medical research on humans that preventing pain is more productive than trying to stop it, that pain diminishes the body’s ability to heal, and that the recovery from any painful illness can be sped along with the addition of pain relievers. We have learned that beginning pain preventative therapy early, before the pain begins, is more effective than if we wait until the patient “tells” us he is in pain. We also know, because humans can talk to us and tell us, that any surgery and many chronic diseases are painful, including arthritis, diabetes, and certainly cancers. Some of these can be extremely painful. We know that severe pain can incite the inflammatory response and a stress reaction, which then induce the release of cortisol, diminish the immune response, induce tissue breakdown, and cause energy mobilization. Taken together, these and other responses to pain can actually shorten the patient’s lifespan as well as diminishing his remaining quality of life. And so, putting all this together, it just makes sense to begin pain control whenever there is the likelihood of pain (surgery, trauma, arthritis, cancers, etc.). We need to begin it early on and continue it as long as periodic reassessments indicate that pain may still be present. But in almost all cases, natural remedies are preferred – because they are non-addictive, likely to provide a broader spectrum of activity (reaching more pain mechanisms than conventional medicines, which are programmed to work at one site only), and there is no known rebound or tolerance effect (opiates, after prolonged use, may actually produce more pain rather than relieving it). Finally, and probably the most important, many of the natural remedies actually enhance healing, whereas conventional pain relievers typically retard the healing process. Examples here include acupuncture, which enhances the immune response; chiropractic, which returns joints to a more normal function, thus allowing the animal to move his joints and restore healing circulation and joint fluids; herbal remedies, which often contain healing antioxidants; and supplements (such as glucosamine), which help to regenerate joint cartilage. Having said all this, it is still important to use whatever pain reliever works. If you and your holistic vet feel that your dog needs a more potent analgesic, then by all means use it. Ongoing evaluation is most important, to help you determine which analgesic works best to relieve your dog’s pains. -Dr. Randy Kidd earned his DVM degree from Ohio State University and his PhD in Pathology/Clinical Pathology from Kansas State University. A past president of the American Holistic Veterinary Medical Association, he’s author of Dr. Kidd’s Guide to Herbal Dog Care and Dr. Kidd’s Guide to Herbal Cat Care.