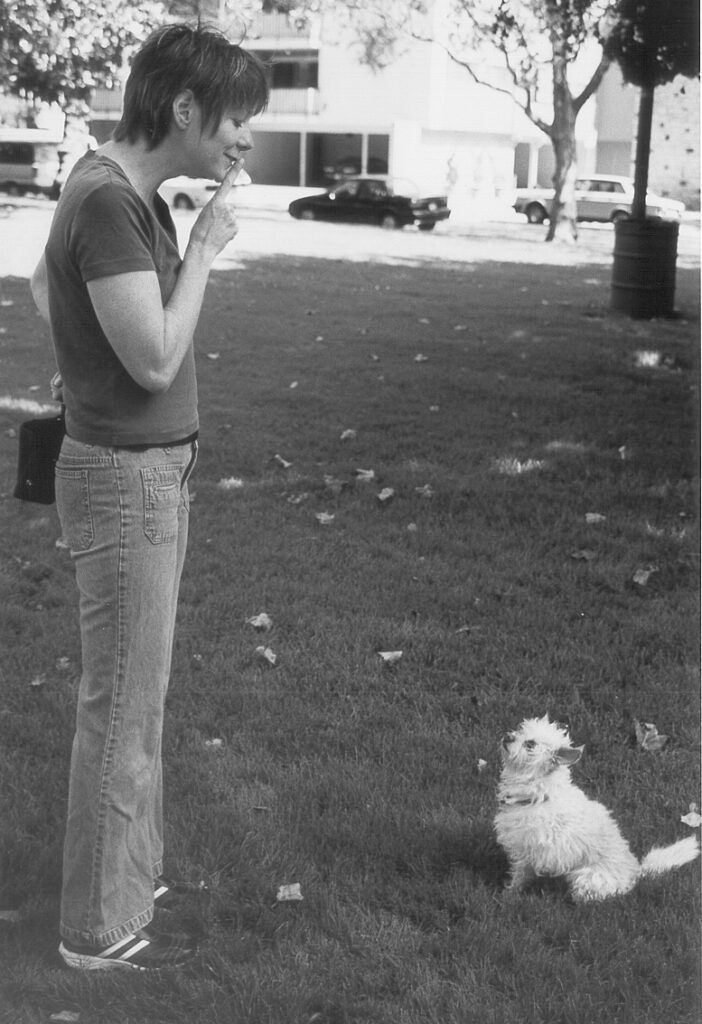

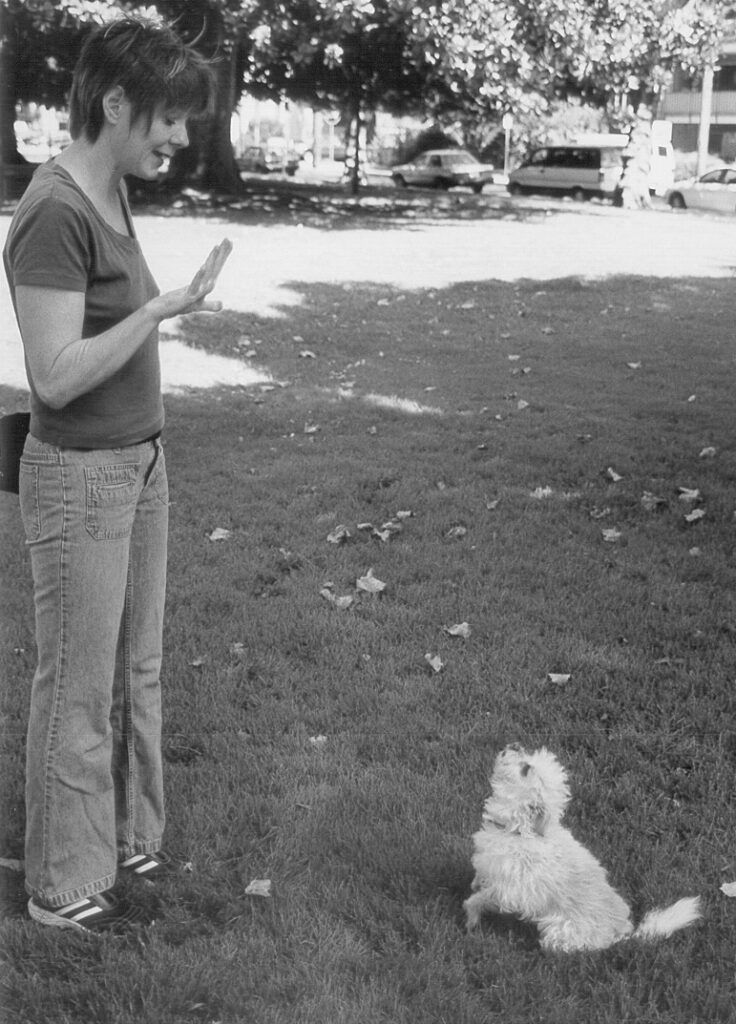

The thought of massaging a dog used to seem – well, weird. Then holistic veterinarians and pet lovers tried it and liked it. More importantly, so did their dogs. Now canine massage is widely accepted as both a primary and support therapy for all dogs, from puppies to active athletes and the elderly or infirm. The health benefits of massage have been known for thousands of years. When done correctly, massage improves the circulation of blood, lymph, and “chi,” the energy that flows through the body’s meridians. It increases flexibility, boosts immunity, and can even improve behavior. Best of all, if you learn to do it yourself, it’s fully portable, available 24/7, and costs nothing. To answer the growing demand for “how to” massage instruction, a number of canine massage therapists have produced instructional videotapes. Now anyone with a dog and a VCR can watch, listen, and practice whenever it’s convenient. The only problem is how to choose which product would be “best” for you! In an effort to help our readers select the “best” tapes, we initially tried to figure out a way to rate the tapes we viewed; then we gave up. What some of the tapes lack in production value, they more than make up in content. And all of them have very different things to offer. Really, the differences are in the presenters’ approach. Some are metaphysical, some are not. Some are more oriented toward working athletes. Some are more geared to the everyday pet owner. Some are “intuitive,” some are point-by-point methodical. These differences are what we have tried to emphasize. For example, people who prefer a spiritual approach (grounding one’s self, asking permission of the dog, aura cleansing, transcendental experiences) will be interested in the videos by Vaughan and Jones, Capps, or Dr. Craft. Someone who wants to boost an agility dog’s performance time will benefit from any of the first five tapes we discuss below. Someone who wants only to help Fido feel a little more comfortable in his old age, and has no interest in seriously studying massage, may enjoy exploring Dr. Basko’s or Wills’ tapes. To sum up, each is a five-star presentation for someone, and each might be a disappointment to someone else, depending on what they want to accomplish. Rather than rate the tapes, we’ve done our best to describe each presenter’s approach and areas of concentration. We’ve also listed contact information and prices (rounded up to the nearest dollar) for all the videotapes. Check the presenters’ Web sites or contact them for information on sales tax, prices on workbooks, anatomy charts, study aids, home study courses, or certification programs, as well as shipping costs to other countries. Jean-Pierre Hourdebaigt The son of a renowned Basque herbalist and healer, Jean-Pierre Hourdebaigt grew up loving dogs, horses, and the traditional healing arts. While visiting a sister in Canada, he decided to move there, and attended the Canadian College of Massage and Hydrotherapy, graduating in 1983. Hourdebaigt became an expert in sports medicine and worked with top Olympic athletes, but his favorite clients were horses. Word spread, and soon he was teaching Massage Awareness™ seminars for horse owners. He published his first book, Equine Massage: A Practical Guide, in 1995. Canine Massage: A Practical Guide followed in 1999, and its revised edition will be published in February by DogWise. The video demonstrates eight classes of massage movements, each of which can be performed with lighter or heavier pressure and at faster or slower speeds. Different combinations are used for different applications and techniques. “For example,” he explains, “we demonstrate how to treat swelling and muscle strains, inflammation from arthritis, and other common conditions. Our trigger point work releases lactic acid from sore muscles and injury sites, and the working of stress points relieves micro-spasms. These last techniques are important for all canine athletes.” For a dog’s first massage, Hourdebaigt recommends the video’s long relaxation routine, which is actually a short sequence of soothing strokes. In addition to relaxing the animal without working too deeply, it provides a beneficial imprinting that helps the dog respond well to future massages. It is also recommended for dogs who have been abused, are anxious, or whose lives are unsettled. “Within two to three sessions,” he says, “they go through a significant transformation.” Joanne Lang Joanne Lang enrolled at the Boulder School of Massage Therapy in Colorado in the 1980s, learning on humans and applying what she learned on horses, with help from several equine chiropractors. As soon as she applied her knowledge of massage to canines, though, Lang realized that she preferred working with dogs. She has focused on dogs for five years. As an instructor and therapist, Lang emphasizes structure. “Most people know very little about structural faults in animals,” she explains, “or even that they exist. Understanding structure helps owners support weak areas and prevent cumulative injuries.” Massage won’t cure a structural defect, says Lang, but caregivers who study massage can help prevent injury by breaking up adhesions and scar tissue that weaken the area and by relieving microspasms. Lang’s favorite success stories involve dogs that could not walk when she and her partner, Terri Coulter, first met them. Thanks to Lang System™ massage, these dogs are leading active lives. “Cases like that are exciting,” she says, “but it’s important for someone who is new to massage to have realistic expectations. If you want dramatic results for serious problems, you’re talking about a year of training and at least five years of practice. Fortunately, you don’t have to be an expert to improve your dog’s health and life, for even gentle massage can make a big difference.” Mary Schreiber In the 1980s, massage therapist Mary Schreiber began applying the techniques she used on humans to horses, dogs, and other animals. To help others learn her techniques, Schreiber developed an equine massage course called Equissage™. Five years ago Schreiber produced her first canine massage video, which was revised and updated when she introduced a canine massage home study course in 2000. Schreiber designed a sequence of massage strokes for horses that she adapted for canine use, and the owners of sled dogs, racing dogs, hunting dogs, and other canine athletes are her most enthusiastic students. “I use the same basic sequence for dogs and horses,” she says, “but I added some new sports massage strokes for dogs. While this muscle therapy was designed for all dogs, it’s especially well suited to dogs whose muscles are overused and overworked.” Most of Schreiber’s strokes involve three applications: gentle, medium, and firm or deep. Some strokes, such as direct pressure, which is used to release muscle spasms, are held for 10 seconds (gentle) to 20 seconds (firm or deep pressure), with a brief release between applications. As she explains, “This sequence prepares the muscles so they stretch without being damaged and without causing pain.” Patricia Whalen-Shaw For more than 20 years, Patricia Whalen-Shaw has been riding horses and massaging large and small animals. In 1992, after becoming a licensed massage therapist for humans, she cofounded Optissage, Inc., and began holding animal (horses, dogs, and cats) massage clinics. As Whalen-Shaw added to her program, it became Integrated Touch Therapy™, Inc., which combines Swedish and sports massage with other techniques in a logical, progressive system. “My method is designed to do no harm and cause no pain,” she says. “It’s soft, and requires patience. That doesn’t mean it isn’t deep or that it isn’t effective. It just doesn’t overwhelm the animal.” Whalen-Shaw’s video is an introduction for the public and a review for those who take her training. She emphasizes proper positioning, so that the person is as comfortable as the dog. “This is important because I want everyone who learns the techniques to use them for a long time,” she says. Her approach involves considerable waiting. “We never force muscles to do anything,” she says. “We stay within the animal’s comfort zone and wait for the tissues to soften and for the protective contracture, or tensing of muscles, to stop.” Whalen-Shaw uses massage industry terminology to facilitate the training of massage therapists, veterinary technicians, and those who work in orthopedic animal rehabilitation. “If a stroke or procedure already has a widely used name,” she says, “I keep it. My program is logical and methodical, and anyone can do it. As long as you stay within your dog’s comfort zone, you’ll do no harm and the dog will benefit.” Jonathan Rudinger Jonathan Rudinger is a registered nurse, a licensed massage therapist for humans since 1996, and a canine massage therapist since 1997. “I started with horses in 1982,” he says. “It’s something I wasn’t really trained to do; I just picked it up. I finally went to massage school in the 1990s, and discovered that what I’d been doing with horses was totally appropriate. I then incorporated conventional massage techniques into my practice.” During a TV program that featured Rudinger, the interviewer brought out an elderly Golden Retriever and announced, “Dogs get stiff necks, too. What can you do to help?” A minute later, the dog melted into Rudinger’s hands. “That was the turning point,” he says. “I knew at that instant that I had skills and techniques that I could share with people to bring comfort to their animals.” Four years ago, he founded the PetMassage™ Training and Research Institute in Toledo, Ohio. In his videos, Rudinger demonstrates hand positions and conventional massage strokes. To these he adds thumb-walking on the face and along the spine and clasped hands, which gently lift the chest and abdomen. His head-to-tail massage includes the eyes, mouth, and gums. “My focus in the videos, in the home study course, and in everything we do here at our training school,” he says, “is on building the connection between the person and the dog and increasing the person’s confidence. If you work with your dog’s permission and follow the instructions, you can’t make a mistake.” Lynn Vaughan, Deborah Jones Although they live on opposite sides of the country, Lynn Vaughan and Deborah Jones have been teaching partners since they worked at a holistic veterinary clinic in California in the 1980s. Vaughan graduated in 1989 from the Swedish Institute of New York City. Jones graduated from the Massage School of Santa Monica, California, in 1986. “As veterinary technicians, we used acupressure and massage with the animals,” says Vaughan. “The results were so inspiring that we decided to pursue practices in bodywork, especially the teaching aspect of including the animal’s person in the circle of healing.” Vaughan and Jones work with dogs who have musculoskeletal issues, degenerative conditions, emotional and physical stress, sports injuries, behavioral problems, aftereffects of surgery, and factors related to service work. They also develop programs for companion dogs, athletes, working dogs, and animals in rescue and rehabilitation. They have prepared dog/handler teams for multi-sport training with techniques that address the physical, spiritual, and relationship aspects of competition. “Our videos emphasize the ingredients of Intuitive Touch,” they explain. “These include centering breathwork, visualization, using a listening touch, nonverbal communication, and loving intention, with a synergistic combination of massage and acupressure. This guides people into developing a deeper understanding of listening and giving, which enhances mutual healing and relationship. Intuitive Touch creates a common ground for connecting, communicating, and exploring the powerful healing potential in the human/animal relationship.” Dr. Ihor Basko A veterinarian since 1971, Ihor Basko studied Japanese acupressure at San Francisco Medical Hospital in San Francisco in 1974, then worked with the late Sebastian Reyes, M.D., who was one of California’s first licensed acupuncturists and OMDs (Oriental Medical Doctors), from 1978 to 1982. “Dr. Reyes was a miracle worker who saved my own back and neck from paralysis,” says Dr. Basko. “He trained me to work on people. First he would massage his patients, then he would use acupuncture, moxibustion, and manipulation therapy to heal his patients. I could not have asked for a better instructor.” In the last 28 years, Dr. Basko has studied with nearly a dozen human bodyworkers, learning about Rolfing, acupressure, acupuncture, Shiatsu, Trager therapy, Structure Integration, and more. In every case, he applied what he learned to animals. Dr. Basko encourages his clients to massage their dogs at every opportunity, including bath time. “Hydrotherapy can transform a routine chore into a healing ritual,” he says. Dr. Basko emphasizes the importance of one’s frame of mind and emotion. “If your head is spinning with too many thoughts, worries, or stress, or if your heart is sad, mad, or feeling hopeless,” he says, “do not try to treat anyone. You need to be healed first. Your energy, good or bad, passes from your psyche into your hands and into your pet. You can make an animal worse if your emotions and mind are out of balance.” In his video and accompanying manual, Dr. Basko reminds us that the most direct way of influencing an animal’s health is through touch. “The magic of touch can do more for a sick animal than any medications,” he says. “With your hands you transfer energy from your body and being to your dog’s body and being. Massage is like a dance in which energy is exchanged. It works best when you have learned the basic techniques and then stop thinking, start feeling, and blend with your dog, yourself, nature, and your higher spirit guides.” Angela Wills Angela Wills has been a licensed massage therapist for people since 1991. In 1995, she studied Optissage™ (now called Integrated Touch) with Patricia Whalen-Shaw. Wills has massaged hundreds of dogs in the last seven years, both in her Florida practice and at agility trials. Not all dogs take to massage right away, Wills warns. “It is more than just petting,” she explains. “Massage moves muscle tissue in a way that it may have never been moved before. Some dogs like it immediately, and others take a while to accept it. If you keep sessions short, your dog will tell you what he or she needs. Eventually, the dog will start to ask for massage by coming up and leaning on you or by just accepting it more and more.” In her video, Wills demonstrates a full-body relaxation massage. “You will always get faster and better results by working with the dog’s whole body rather than just the part that shows symptoms,” she says. “Any postural changes, even minor ones, throw other parts of the body out of alignment. Work gently in areas that are weak or painful, like sore hips; work more deeply in areas that are bulky or overdeveloped, like the shoulders of a dog with sore hips; and work with all the other parts to restore proper alignment.” Wills describes her target audience as anyone who wants to do the best for his or her dog. “You don’t have to be a trainer, veterinarian, or massage therapist to apply these techniques,” she says. “Be open to the benefits of massage. Listen and watch your dog while massaging. Your dog will tell you how it feels and what needs to be done.” Dr. C. Joy Craft A holistic veterinarian, C. Joy Craft is also a massage therapist who studied the art in Hawaii. She applied what she learned about humans to dogs, horses, and other animals. “As soon as I did,” she says, “my relationship with my patients changed for the better, and so did their health.” Despite her conventional training, Dr. Craft describes her approach to medicine as primarily spiritual. “I emphasize the importance of sending healing energy from your body into the animal you’re working with,” she says. “This simple process is the key to keeping pets healthy and happy.” In her video, which was taped at an outdoor seminar, Dr. Craft introduces dogs and their owners to a variety of holistic therapies, including aura cleansing, acupressure, aromatherapy, and color therapy. “I encourage everyone to begin every massage session with a cleansing of the animal’s aura,” she says. “It takes only one or two minutes, but its benefits are substantial. This removes layers of negative or harmful energy that dogs absorb from the people around them. I consider aura cleansing the most important thing we can do for our dogs.” In massage, Dr. Craft focuses first on fascia, the dense connective tissue that is the muscles’ protective cover. This tissue tends to become tighter, less flexible, and more restrictive with age and injury. “Fascia is the enemy,” she says. “It restricts the nerves as well as the muscles. Massage melts the fascia and causes it to relax, which makes the animal more comfortable and flexible.” Dr. Craft also massages around the dog’s eyes – an impressive demonstration – and offers a detailed display of a step-by-step emergency massage for injured animals that combines diagnosis and treatment. “My goal,” she says, “is to help people understand their dogs’ bodies, recognize minor problems, and prevent them from becoming serious illnesses or injuries.” Helen Marie Capps In 1994, Helen Marie Capps received a pet care video by Dr. Michael Fox. In the middle of the video was a section on how to massage a dog. “I sat down with Apache, my ancient Brittany, and barely got past his ears before he fell over in a relaxed and happy heap,” Capps describes. “Then I worked on Abby, who never wanted to be touched and was generally anxious about everything. To my amazement, she relaxed, too.” Capps read books and attended classes in human massage therapy. In 1999, she graduated from Jonathan Rudinger’s PetMassage Training and Research Institute in Ohio. Today she offers dog massage services and instruction in canine massage. Many of her clients are canine athletes, but some are dogs with serious medical conditions, like the German Shepherd whose veterinarian recommended euthanasia because the dog’s degenerative myelopathy would paralyze him within four months. With twice-weekly massages, the dog remained active and mobile for four years, going for walks until two weeks before his death at 14. “Most of what I do is intuitive,” says Capps. “It’s hard to explain, but sometimes I just seem to know things, like where I should focus or how a dog has injured himself. My approach is as much a philosophy as it is a technique. I try to share this approach on the video. Once you stop trying to do the work and simply let go, the guidance comes. As long as you’re gentle, you’ll intuitively do the right thing.” Deborah Kazsimer This video differs from all the others in that the presenter is not a professional canine massage therapist. Rather, she became an “expert” in meeting her own dog’s special needs, and then guessed (correctly) that other people whose dogs’ suffered similar problems would also benefit from what she had learned. Deborah Kazsimer’s German Shepherd, Sheba, led a charmed life until she developed degenerative myelopathy, an incurable spinal cord illness that causes progressive paralysis. Sheba was eight when she was diagnosed in the summer of 1999. Thanks to the unstinting efforts of her human family, her life remained wonderful, for the Kazsimers found innovative ways to care for her even after she lost the use of her hind legs and, one year later, her front legs. In her video, Deborah Kazsimer tells Sheba’s story and demonstrates the therapies that sustained the dog. The most important was massage, for without the circulation it provides, quadriplegic dogs deteriorate rapidly. Even in her final months, Sheba’s gums were pink, her eyes were clear, her skin and coat stayed healthy, and she remained alert and interested in the world around her. Anyone with a physically disabled dog would benefit from the information in this video. Click here to view “Compression Techniques for Muscle Strength” Click here to view “Dog Massage 101”

Good Books On Positive Training Techniques

As the holidays approach, many of us are on the lookout for gift ideas. Good books are always a great and easy choice for your dog-loving friends, especially (in my view) good books about positive training techniques and theories based on sound scientific principles of behavior and learning.

The training field is now producing a steady stream of books that offer instruction and guidance, and many of them appear to promote dog-friendly training methods. But you can’t always judge a book by its cover! It’s more than disappointing to order a promising volume with a “positive” title, only to discover that hidden within the pages are suggestions to jerk on collars, glare into your dog’s eyes, and worse.

Unfortunately for the average dog owner, many of the best books are either published by small houses or self-published, which means they may never appear on the shelves of large chain bookstores. We rely heavily on a specialty distributor, DogWise (at 800-776-2665 or www.dogwise.com), to learn about and order dog books.

Here are eight of our favorite new books (from 2001 or 2002) about behavior or gentle, dog-friendly training. All of these books are free of training methods that are based on force or intimidation. We’ve also included a guide to help you decide which of your friends each of the books is best suited for:

N = Novice Dog Owner. Good, simple, basic training and care information.

I = Intermediate Dog Owner. Beyond basic; still easy for the lay reader to follow.

P = Professional, Aspiring Professional, or Advanced Dog Owner. Presents more technical information and/or requires more serious commitment to dog training.

Note that some books may be appropriate for two or even all three categories.

Get Online

Frequently Im asked about the WDJ Web site (whole-dog-journal.com). What does it cost to access articles online? Do the articles posted online differ from whats presented in the print version of the magazine? And why arent the old articles free? Let me take this opportunity to explain.

Online access doesnt cost the reader any more than a conventional subscription; neither does it cost less, since at present, our publisher does not offer an online version only subscription. Right now, the online version is a bonus; when you pay for a regular subscription, you are given the option of registering for online access. You provide an e-mail address, confirm your subscription status, and choose a password; then you can view articles in the current issue online and in print.

This offers a few advantages. One is that the online version is published before the print version is mailed, giving you early access to the newest issue. Another is that you can read the current issue while at the office (say, when your paper copy is at home). You can also click on hyperlinks for Web sites referenced in the articles too cool!

However, only the current issue is available online. If you want to read past articles, you have to refer to your old print copies, just like before. Or, if you are really desperate to read something from a past issue right away, you can pay for the privilege of immediately downloading an Adobe Acrobat (pdf) file with the article you want.

Given the fact that I already have each issue on my computer (where each issue originates), I dont really need to access articles online. However, I do constantly use the search feature on the Web site. I used to refer frequently to the indices that we print in each Decembers issue, the ones that list all the articles from the past year, arranged by topic category: training, health, nutrition, etc. Now, with my always on cable modem and a bookmark set to the search page, I can locate past articles by topic or keyword almost instantly. Once I know in which issue an article was published, I can grab my binder of print issues from the correct year and turn right to the article I want.

Of course, if you prefer, you have the option of having a regular, printed copy of a past issue mailed to you. This way, you receive the entire issue in which the article appeared.

Why dont we just give away old articles and issues, or allow everyone to read WDJ online? Because subscriptions and back issue sales are what keep us in ink and pixels. By shunning advertising sales and income, we can maintain an independent editorial view, keeping us free to discuss topics the ad-dependent magazines are pressured not to print.

-Nancy Kerns

What You Should Know Before Your Dog Receives Anesthesia

This procedure will require general anesthesia.” There are few statements that a veterinarian can make to a dog owner that causes more alarm and misgiving, sometimes greater than the anticipated procedure itself. Throughout the years, companion animal guardians have come to suspect that general anesthesia presents a threat to all but the most robust animals, and should be avoided if at all possible.

However, modern advances in all phases of veterinary medicine, including anesthesia, enable today’s veterinarians to significantly improve the length and quality of our companion animals’ lives, and perform lifesaving and life-enhancing treatments previously considered too risky or too complicated.

As in human medicine, however, veterinary healthcare consumers must choose from a variety of options for the surgical care of their dogs. Understanding the issues surrounding the use of anesthesia, the needs of their particular dogs, and the complementary or holistic care practices that can support an animal undergoing anesthesia will enable companion dog owners to provide the best possible guardianship of their animals.

Types of anesthesia

The definition of anesthesia is “without pain,” and anesthetic agents enable veterinarians to perform medical procedures on animals safely and humanely.

Local anesthetics, such as an injection of lidocaine to perform a skin biopsy, provide for the short-term “deadening” of a small site on a patient that remains fully conscious. Regional anesthesia requires the injection of the anesthetic into the nerves or around the spinal cord to cut off the sensation of pain from the surgical site. Regional anesthesia blocks only pain impulses from the part of the body being anesthetized. The patient is fully conscious and her vital signs normally remain unaffected.

Although extremely safe, local and regional anesthesia do have their drawbacks. Mostly useful in treating minor problems of the skin, the dog is awake and can struggle during the procedure. Physical restraints may further excite an already agitated dog, and complications arising during surgery may be difficult for the doctor to control or treat.

General anesthesia produces a state of complete unconsciousness and the total loss of feeling in the entire body during its administration, and for a time thereafter. Although general anesthesia does carry some risk of serious, adverse reactions, it has revolutionized the safety, quality, and range of surgical treatments offered to dog owners.

General anesthesia

The process of administering general anesthesia in anticipation of a surgical procedure includes several distinct phases or steps:

Preparation and premedication, when the doctor evaluates and treats the dog prior to the surgical procedure, and the owner prepares the dog for the surgery.

Induction, when the veterinarian administers a general anesthetic and takes the dog to a level of unconsciousness suitable for the surgical procedure.

Maintenance, when the veterinarian or the anesthesia technician maintains the dog in a state of unconsciousness, and the doctor completes the surgical procedure.

Recovery, when the dog returns to consciousness, begins to heal from the procedure, and eventually resumes normal activity levels.

Let’s discuss the elements of each of these phases of the process of administering general anesthesia, and discuss the options available for the care of your dog.

Preparation, premedication: Countdown to surgery

Suspend the use of all herbs at least 48 hours before the surgery, and advise your veterinarian if you use these remedies. Some herbs may thin the blood or interfere with the proper administration of anesthesia.

Prior to administering an anesthetic and performing an elective surgical procedure, a veterinarian will examine your dog completely to determine if she is in general good health. Usually, the veterinarian will draw blood before the day of surgery, especially if the patient is an older dog, or one whose health is compromised by injury or illness. The doctor will check the blood count for signs of anemia or a high white blood cell count that may indicate the dog has an infection.

A blood chemistry profile indicates to the doctor if the dog’s kidney and liver functions are normal. These tests are particularly important for dogs seven years or older, dogs with a recent history of kidney infection or other illness, and young dogs with congenital defects, such as a heart murmur. The veterinarian will refer to these test results before selecting the anesthesia protocol for your particular dog.

Although many veterinarians do not insist on performing a preoperative blood test for young, apparently healthy dogs, it’s worth the investment (about $70) to screen closely for any indications of hidden health concerns before scheduling surgery.

Follow your veterinarian’s instructions about giving food and water to your dog at home, before and on the day of surgery. Most doctors require owners to make food and water unavailable to the dog at least 12 hours before the surgical procedure. An empty stomach will prevent vomiting if the anesthesia makes the dog nauseous.

If your dog is particularly anxious at the veterinarian’s office, or suffers from separation anxiety, ask your vet whether you can bring the dog to the hospital just prior to the scheduled surgery, to reduce any time she may have to spend caged in a holding area before surgery. Although most veterinary hospitals have “drop-off” times early in the morning, even for dogs whose surgeries are scheduled for hours later, your good relationship with your caring veterinarian should encourage the doctor to permit you to bring your dog to the hospital just before the procedure, and to accompany her up to the time of surgery.

Some veterinarians may give the dog a mild sedative to relax the dog before the procedure. A particularly anxious dog may benefit from receiving a mild tranquilizer while you are still with him, before he has a chance to get “worked up” in your absence.

A tranquilizer called acepromazine is commonly given to dogs prior to anesthesia induction. “Ace” (as it is commonly known) should not be given to epileptics or other dogs who are susceptible to seizures, as it can lower the seizure threshold and cause seizure activity. Make sure you let your veterinarian know if your dog has ever had seizures so he can avoid using this drug.

The doctor may clip a patch of hair on the dog’s leg and insert an intravenous (IV) catheter, which will administer intravenous fluids to support the animal during surgery. Especially beneficial for older dogs, IV fluids help keep the dog’s blood volume and blood pressure stable. Fluids also help the dog replace lost blood quickly, and assist in flushing toxins from the dog’s system.

Induction

The act of creating a state of unconsciousness, muscle relaxation, and analgesia (freedom from pain) through the administration of a general anesthesia is called induction. Most commonly, veterinarians use a quick-acting, injectable anesthetic drug to swiftly “knock out” the dog before moving on to the next phase of anesthesia, which is maintenance.

Sometimes, injectable anesthetics are used as a sole agent to induce a short period of restraint for minor, non-painful procedures, such as radiology and ultrasound examinations, but in surgery, the injectable agents are most often used to quickly bring the animal to the “surgical plane” of unconsciousness, after which inhalant (gas) anesthetics are used to maintain anesthesia.

Once an injectable anesthesia enters the dog’s body, it remains in the fatty tissue until the liver metabolizes it, or the dog receives a reversal agent. Not all injectable anesthetics have reversal agents and, in the case of an overdose, the doctor can only provide supportive care until the agent leaves the dog’s system, usually in 40 – 60 minutes.

Some dog owners and veterinarians have concerns about using the combination of injectable and inhalant anesthetics in certain breeds. Brachycephalic (flat-faced) breeds such as Pugs, Bulldogs, Boston Terriers, and Shih Tzus are reportedly prone to complications such as respiratory depression when subjected to the anesthetic combination.

Greyhounds and other sighthounds (Whippets, Afghans, Salukis, Borzois, Wolfhounds, Deerhounds) sometimes exhibit a delayed drug metabolism, with prolonged anesthesia resulting from a combination of anesthesia drugs. Some have attributed this to a low percentage of body fat (where anesthetic drugs are stored before being processed and excreted by the liver and kidneys); other speculate that these dogs lack the oxidative enzymes in the liver that are needed to metabolize the drugs normally.

Guardians of these dogs sometimes ask their veterinarians to forego the use of the injectable drug, and “gas down” their dogs with inhalant anesthetic alone. This practice is controversial, however. Many animals panic when an inhalant anesthetic is used to induce unconsciousness, since a mask must be placed over their faces and the anesthetic they breathe may concern them. Struggling during gas induction raises the heart rate of the dog and causes the animal unnecessary discomfort. Also, escaped gas from mask inductions is wasteful and may be dangerous to the hospital personnel attending the dog, so many veterinary practices avoid this type of induction.

Again, communication with your veterinarian is key. Talk to her about your concerns, and ask about her anesthesia protocol for the type of dog you have. If you feel your concerns are being brushed off without full consideration or explanation, find another veterinarian to work with.

Propofol is the newest injectable anesthetic, used in human medicine and introduced into veterinary practice in 1987. For induction purposes, Propofol works rapidly and the dog slips into unconsciousness quietly and with little excitement. The drug is metabolized quickly by the dog’s body, and offers a short, smooth, and high-quality recovery. Many practices use this agent for outpatient surgeries. However, propofol is short-acting and difficult to adjust when used for hours at a time, so it is not appropriate for lengthy procedures.

Older types of injectable agents, such as ketamine, are less expensive, but may cause some spontaneous muscle activity upon induction and dogs tend to experience a rougher recovery period. Ketamine is usually mixed with diazepam (Valium) or another sedative or tranquilizer to control these effects.

After inducing the animal, the veterinarian places a tube through the dog’s mouth and into the trachea (windpipe). The doctor then connects the tube to a machine that delivers an inhalant anesthesthetic for the maintenance portion of the process; then he prepares the surgical site.

Maintenance

Sevoflurane is the latest inhalant anesthetic available for use in veterinary medicine. Isoflurane and, to some extent, halothane are most widely used. More expensive than the older agents, sevoflurane is noted for creating a speedy induction and recovery, and its relatively pleasant odor. However, due to the preference for IV inductions, the speed of induction with sevoflurane is not clinically important.

The anesthetist can titrate (adjust the strength) of gas anesthetics much easier than injectables, so it’s easier to manage the dog’s unconscious state using this method.

Dogs should be kept warm during surgery, especially extended procedures. Many clinics place their patients on special pads that contain circulating warm water to keep them from getting chilled. At a minimum, the dog should be covered with warm towels or blankets for a long surgery.

One of the most important factors in the maintenance phase of general anesthesia is the monitoring of the patient, both by the presence of an anesthetist and the utilization of various pieces of operating room equipment.

An anesthesia technician should watch the dog during surgery, looking for good, pink color in the dog’s gums and skin, and take the dog’s blood pressure periodically to check for proper circulation of the blood. Most doctors rely on a non-invasive pulse oximeter, which measures the oxygen saturation in the dog’s arterial blood. An electrocardiogram (EKG) monitors the electrical activity in the dog’s heart and indicates if the animal’s heart beats too quickly or too slowly or develops arrhythmias. An audible apnea (suspension of respiration) alarm may be used, but some consider it unreliable and inaccurate.

Ventilation equipment is often used during extended surgical procedures. Under anesthesia, animals do not breathe as deeply, nor do they fill their lungs and “sigh” as regularly as they do when they are awake. In effect, their lungs collapse slightly under general anesthesia. By occasionally squeezing the breathing bag attached to the ventilation equipment for the animal, the anesthetist can periodically fill the animal’s lungs, keeping them healthy and the dog’s blood properly oxygenated.

The services of a veterinary technician or anesthetic nurse and the utilization of monitoring equipment all add cost to the surgical procedure. However, they significantly contribute to the safety of your dog while under general anesthesia.

Lore Haug, DVM, and a member of the Department of Small Animal Medicine and Surgery at Texas A&M’s College of Veterinary Medicine, states that the minimum monitoring support she would personally require for one of her own animals about to undergo surgery is the presence of an anesthesia technician to watch and ventilate the animal, a pulse oximeter, and an EKG machine. She adds that the more ill an animal is at the time of surgery, the more different types of monitoring it will require during the procedure.

Inhalant anesthetics also provide analgesia, or pain relief. Pain is a sensory and emotional response to the stimuli that results from damage to bodily tissue. As a result of mechanically manipulating the tissue and organs, as in a surgical procedure, or by enduring thermal or chemical damage, the body reacts with the sensation of pain.

The American College of Veterinary Anesthesiologists’ position paper on the treatment of pain in animals suggests that the need for adequate pain relief is more compelling now than ever before, as modern anesthetic practices provide for rapid recoveries after surgery. Most surgical practices provide for initial postoperative pain relief through the administration of inhalant agents administered during surgery.

Recovery

The dedicated care of a veterinary professional to manage the dog’s recovery from general anesthesia until the end of the anesthetic period is as important as the surgical skill of the operating veterinarian. Some anesthetic agents take more time to clear from a dog’s system, and a recovering dog may show signs of lethargy, loss of appetite, or diarrhea. A dog must be monitored carefully and kept warm and hydrated for a prompt, smooth recovery.

Assuming the absence of complications during surgery, arrange to visit your dog as soon as possible after surgery; bring him home as soon as possible when cleared to do so. Your presence will calm your dog and reduce his stress and discomfort.

Some veterinarians apply a fentanyl patch to the dog’s chest to deliver pain medication through the dog’s skin and directly into his blood stream. Consult with your veterinarian about pain relief medications that may be needed during recovery at home.

Adjuncts to conventional care

Perhaps the most valuable aspect of holistic medicine is as a support for the animal’s life force or spirit during a health crisis. Many complementary care methods have an “energy medicine” component that can boost a compromised animal’s healing response. These include acupuncture and acupressure, Reiki, homeopathy, flower essence therapy, and aromatherapy, as well as herbal medicine.

Many holistic practitioners have a protocol for dealing with the psychic and physical effects of anesthesia.

Deborah Mallu, DVM, a holistic veterinarian in Sedona, Arizona, focuses on the psychic effects. Dr. Mallu reminds her clients that the external world is a reflection of the mind. Therefore, she favorably affects a dog’s external, or bodily, world by bringing peace to his inner world. She creates a positive, supportive space in her operating room by playing relaxing or spiritual music during the procedure, and engaging in only positive conversations, focused on the patient.

Dr. Mallu also assumes that the dog retains some level of consciousness even during general anesthesia, and speaks positively about the outcome of the procedure and the health of the dog at all times. She visualizes herself on her patient’s team, working with the dog to improve his health, rather than as a repairman attacking the dog’s body.

Dr. Mallu encourages her clients to visualize and explain to the animal what’s going to happen during the procedure. Rather than comforting the animal by describing what will not happen (“Don’t worry, it won’t hurt for long, you aren’t going away forever . . . ”) she suggests telling the animal what will happen (“You’ll be in the hospital for a short time, relaxed and pain-free during surgery, and home again before long. We can help you to feel only a little pain after the procedure.”). This approach short-circuits fear-based thinking and creates positive and emotionally stable interactions with your dog.

She keeps a flower essence remedy known as Rescue Remedy available for herself, her clients, her patients, and her staff members to settle the mind. During surgery, she may ask her technician to administer a homeopathic remedy to her patient, such as phosphorous to decrease bleeding and to help alleviate the effects of anesthesia following the procedure. Dr. Mallu may give aconite or arsenicum album to a very fearful animal.

The occasional use of single remedies, as described by Dr. Mallu, is not in keeping with the tenets of classical homeopathy, where remedies are selected based upon a comprehensive understanding of the entire animal. However, Dr. Mallu considers the above-mentioned remedies broadly functional for such as wide range of conditions that their use is occasionally warranted under her supervision. She does not administer these remedies if the animal is already under the care of a classical homeopath.

Dr. Mallu may administer acupuncture while the dog is asleep to control pain, bloating, and nausea following the procedure. She also strongly emphasizes the importance of “gentle tissue handling” during surgery, and minimizes postoperative pain by being particularly mindful that much of that pain results from the harsh handling of the dog’s tissues and internal organs. Dr. Mallu always closes with absorbable, subcuticular (under the skin) closures to maximize comfort at the incision site and discourage the dog from licking or biting at the sutures. In more than 20 years of veterinary surgery, Dr. Mallu has never used an Elizabethan collar to prevent a dog from biting at his incision, and makes minimal use of analgesics after surgery. She has a small cottage adjacent to her surgical suite in which the dog’s guardian can hold the animal, wrapped in a blanket, while the dog regains consciousness.

Dr. Mallu rarely uses aromatics to help with recovery after surgery because the dog has already received inhalant anesthesia. However, when indicated, she may fill a half-pint spray bottle with 3 drops of lavender oil, 10 drops of Rescue Remedy, and pure water, and spray the mixture lightly around the dog.

At home, she advises her clients to keep the dog comfortable and their own mind stable to help with the emotional recovery of the animal.

Acupuncture and acupressure

Chris Bessent, DVM, a Milwaukee-based holistic veterinarian, acupuncturist, and herbalist specializing in sports medicine for horses and dogs, concentrates more on the physical aftereffects of anesthesia.

In Dr. Bessent’s opinion, the anesthetic process is not over when a dog regains consciousness after general anesthesia. “Holistic doctors know that the anesthesia process often continues on for weeks after the treatment,” she says.

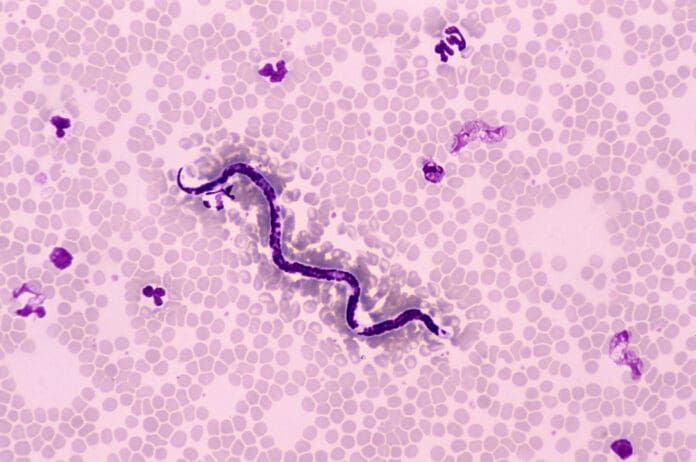

She explains that many dogs develop a liver qi (pronounced “chee” and understood as the energy or force associated with life and life processes in living beings) stagnation from the effects of general anesthesia. Anesthetics are toxins that the liver must eliminate, with a significant effort.

Dr. Bessent usually treats a dog one to two weeks after it receives general anesthesia. She performs a “pulse diagnosis” by taking the dog’s pulse at 12 positions on the dog’s femoral arteries in the hind limbs. After anesthesia, 90 percent of the dogs she examines have a “superficial” pulse that feels taut, like a wire. A “normal” or “balanced” dog’s pulse is moderate and not too tight.

Dr. Bessent also performs a “tongue diagnosis” and finds that 90 percent of dogs that have recently received anesthesia have a purple to red tongue, indicating a condition of “heat” caused by a liver imbalance. A healthy dog’s tongue is pink.

A few dogs are capable of “righting” themselves completely after anesthesia, but most show mild to significant long-term reactions to the anesthesia process. “Remember,” Dr. Bessent explains, “these reactions are not the direct result of the general anesthesia itself, but the result of the reaction of the dog’s liver to the anesthesia, which can then be treated.”

To correct liver qi stagnation, Dr. Bessent uses acupuncture and combinations of Chinese herbs, including coptis and scutellaria, or, sometimes, long dan xie gan tang. Dr. Bessent may recommend the herbal combination “Great Mender” to help speed healing for traumatized tissue. (Visit Dr. Bessent’s Web site at herbsmithinc.com for more information about herbal remedies.)

Normally, after a single acupuncture treatment and dose of herbs the dog is back to normal, as Dr. Bessent confirms with a follow-up pulse and tongue diagnosis. Older dogs, who are more difficult to “balance” following anesthesia, may require a second course of treatment 10 days to two weeks after the initial treatment.

Dr. Bessent points out that if guardians do not fully resolve the aftereffects of anesthesia on their dogs, a number of conditions may plague the dog afterward, mostly inflammatory in nature and settling into one place in the dog’s system. These conditions include the beginnings of allergies, gastrointestinal upset (vomiting and diarrhea), inflamed eyes, anal sac problems, vaginitis, seizures, and even irritability and aggression.

On occasion, Dr. Bessent will examine a dog before it undergoes anesthesia. She performs a preoperative pulse and tongue diagnosis, and balances the dog, if necessary, with acupuncture. She advises her clients not to administer any herbs to their dogs within 48 hours of surgery.

“General anesthesia is a necessary and safe process,” Dr. Bessent says. “But animals need more supportive care surrounding the event to reduce or eliminate imbalances following treatment.”

Keep in mind

Modern general anesthesia provides the veterinarian with one of her most useful health care tools. Guardians can embrace anesthesia as an important aid in their dog’s lifelong health care, providing for less apprehension and better overall outcomes for your dog.

Become informed and share your desires about general anesthesia with your veterinarian. If she is not sensitive to your concerns, consider selecting another practitioner. Incorporate traditional and holistic practices into your support regimen for your dog, and enjoy the longer and healthier life your canine companion can experience with the help of today’s sophisticated veterinary medical techniques.

Also With This Article

Click here to view “What You Should Know About Anesthesia Before You Schedule Your Dog’s Procedure”

-by Lorie Long

Lorie Long is a frequent contributor to WDJ. She lives in North Carolina with two Border Terriers, Dash (a three-year-old female and agility queen) and Chase (a five-month-old male with an agility future).

Download the Full October 2002 Issue

Subscribe to Whole Dog Journal

With your Whole Dog Journal order you’ll get:

- Immediate access to this article and 20+ years of archives.

- Recommendations for the best dog food for your dog.

- Dry food, homemade diets and recipes, dehydrated and raw options, canned food and more.

- Brands, formulations and ingredients all searchable in an easy-to-use, searchable database.

Plus, you’ll receive training and care guidance to keep your dog healthy and happy. You’ll feed with less stress…train with greater success…and know you are giving your dog the care he deserves.

Subscribe now and save 72%! Its like getting 8 issues free!

Already Subscribed?

Click Here to Sign In | Forgot your password? | Activate Web Access

Here to Help

I know Ive said this before, but I really am one of the biggest beneficiaries of the articles in WDJ. Each and every article has helped my dog or some dog I know.

For example, in the course of researching and writing about canned foods for this issue, I found some great new products to give my dog, Rupert. While editing the article on oral health I learned why I had better hurry up and schedule a complete dental exam and cleaning for him. At almost 13 years old, Rupert has never needed a teeth-cleaning before, but he recently began developing tartar and even a little gingivitis. I also know what questions to ask my veterinarian about the anesthesia before scheduling an appointment.

Rupert has a heart condition that is kept under control with medication and a special herb tea. He passed a recent cardiology checkup with flying colors, and his overall energy and condition is good. But there is no denying that hes an aging dog, and his hearing is deteriorating rapidly. Its gotten to the point where you can walk up behind him calling his name loudly, and he only cocks his head and peers forward, with a Did I just hear something? look on his face. Fortunately, he can still hear hand-claps, which is how we now get his attention; then we use hand signals and semaphore flags (I exaggerate, of course) to tell him what to do and where to go. It seems silly with such a well-behaved dog, but Rupe is an obsessively compliant dog who feels more relaxed when told to Down-stay! than when he is left to lie down under his own volition. This is anthropomorphizing, of course, but I think the fact that I can still order him around and reward him for his usual obedience means a lot to him. Pat Millers article on hand signals has helped us a lot.

By the way, in The Price of Prescriptions in the September issue, I mentioned a dog named Chase, whose guardians were paying about $80 a month for his Prozac prescription. When I interviewed them for the article, which was about ways to save money on veterinary prescription drugs, I had encouraged them to shop around for a better price for their dogs prescription. I even found a pharmacy close to them that sold a months worth of a generic form of the medicine for $64.

Shortly after the September issue went to press, I received a message on my voice mail from Kelly. Thank you, thank you, thank you for telling us to shop around, the message began. I took Chases prescription to Costco the other day, and was given a price of just $9.45 for a months supply, and $12.96 for two months worth of Chases pills. Your article has saved us a fortune.

Like I said, it pays to subscribe!

-Nancy Kerns

Whole Dog Journal’s 2002 Canned Dog Food Review

When I was a kid growing up in the country, my family’s dogs ate a pelleted food that came in 50-pound burlap sacks from the same feed store where we purchased hay and grain. The food looked more like chicken feed than anything else, but our dogs cleaned it up.

Until I was about 12, the only canned pet food I ever saw was at my grandmother’s house. She lived with one of my uncles in the city, and fed my uncle’s fat orange cat a small can of food every day. As a tomboy used to romping barefoot around the countryside with a pack of dogs, I thought the city was unbearable, the cat spoiled, and the cat’s food repugnant. Surely only sissy cats and foo-foo dogs ate that stinky stuff!

As I grew into adulthood, I learned to feed my dogs dry foods that have steadily increased in quality. But I overcame my life-long bias against canned foods only a couple of years ago, when I found out that top-quality canned pet foods are actually quite healthy, perhaps more so than dry foods. They should never be dismissed as being a frou-frou luxury for spoiled pets, as I regarded them for decades.

Canned foods are frequently made with higher-quality ingredients than their dry counterparts, including fresh, whole meats, grains, and vegetables. They generally contain a higher percentage of meat than dry foods, if for no other reason than because dry food extruders can’t handle foods that contain more than 50 percent meat. Also, canned foods usually contain way fewer chemical additives than dry foods. Artificial colors and flavors are actually uncommon in canned products; because of the moist, fragrant nature of the meat-based contents, artificial flavoring and other palatants are rarely needed to attract dogs to otherwise unappealing food.

Of course, palatability is why the guardians of fussy old dogs and cats end up buying canned foods you don’t want older or sick animals skipping meals. But the higher palatability of canned foods also indicates that the food more closely resembles what dogs are hard-wired to enjoy, namely, meat! Dogs generally like canned food more than kibble because it tends to contain more meat and more fat than dry food.

Canned food also tends to have a higher energy content, ounce for ounce. Its high moisture content is helpful for dogs with cystitis or kidney disease. The high moisture content can also help a dog who is on a diet feel full faster.

In addition, added preservatives, which are ubiquitous in dry foods are unnecessary and rarely seen in canned foods, due to the sealed, oxygen-free environment that a can offers. (This does not mean the foods are free of preservatives altogether; some ingredients arrive at the food manufacturing plants already preserved. As long as the maker does not augment the food with additional preservatives, this hidden ingredient does not have to be declared on the food label.) Because they lack added preservatives, canned foods must be kept refrigerated after opening.

WDJ’s selection criteria

Of course, not all canned dog foods are full of fabulous, healthy ingredients. As with every other sector of the commercial food industry, there are lots and lots of subpar products on the market, and a small, select group of top-quality products.

Here’s how we determine which foods are which. We required the following for a product to make it into the running for our Top Canned Dog Foods:

We eliminated all foods containing artificial colors, flavors, or added preservatives.

We rejected any food containing meat by-products or poultry by-products. (Please note that in past years, we did select some foods that contained meat and poultry by-products. We don’t think by-products are necessarily bad; they just aren’t as good as muscle meat. In order to winnow down our list to the very best foods possible, we no longer include foods that contain meat or poultry by-products.)

We rejected any food containing fat or protein not identified by species. Animal fat is a euphemism for a low-quality, low-priced mix of fats of uncertain origin. Meat by-products can be from any mammal or mix of mammals. These ingredients come to the food makers at bargain-bucket prices, and accordingly, may not have been handled as carefully as more valuable commodities.

One borderline case: poultry fat. We’d prefer to see chicken fat, for example, than a mix of fats, potentially bought and mixed from various sources. But we have selected a couple of foods that contain poultry fat.

We eliminated any food containing sugar or any other sweetener. A food containing quality meats shouldn’t need additional palatants to entice dogs.

We looked for foods with whole meat, fish, or poultry as the first ingredient on the food labels. By law, ingredients are listed on the label by the total weight they contribute to the product. Water is necessary for the manufacturing process used to make canned foods, but in lower-quality products, water is usually the first ingredient. (Again, in past years, we selected some foods that featured water in the first position on the label; we are tightening up our list.) It’s not a requirement, but we like it when a nutritious meat, poultry, or fish broth is used in place of water.

We looked for the use of whole grains and vegetables, rather than a series of reconstituted parts, i.e., rice, rather than rice flour, rice bran, brewers rice, etc.

We award theoretical bonus points for foods that offer the date of manufacture (in addition to the usual best if used by date), nutrition information beyond the minimum required, and any organic ingredients. Expensive and hard to find

It may come as a shock to learn that the best foods for your dog the ones that contain only top-quality whole-food ingredients are both more expensive and more difficult to find than foods whose names you may be more familiar with. Just as with human foods, the dog foods that are produced and sold in the largest quantities in this country are not the healthiest foods.

This principle is also true of human foods, so it shouldn’t be a surprise. If you go to a large chain grocery store in search of processed foods that don’t contain numerous food fragments, preservatives, artificial colors, etc., you’ll soon discover these sorts of products are uncommon there. You might see 15 different types of macaroni and cheese mix on the shelf, but you probably won’t find even one that doesn’t contain artificial colors, flavors, and more than 30 ingredients unless you go to a health food store or a gourmet food store. In these small, independently owned and operated shops, you’ll find all sorts of foods that were manufactured without additives and fragments. In these stores, a box of macaroni and cheese mix might be $2.79 rather than $0.69, but it will contain just four or five healthy ingredients and taste great, too.

Not rank-ordered

Our Top Canned Food selections are listed alphabetically on the next page. We don’t rank-order our selections; all of the products listed on the chart meet our criteria for top-quality foods.

Please don’t regard the products on our list as the only good foods, or even as the best foods on the market. We don’t pretend to know about every food on the market. There are probably hundreds of foods available somewhere in the U.S. that we dont know about. Some of these may meet our selection criteria for a top-quality canned food; you can easily determine this for yourself by comparing the ingredients listed on the food with our selection criteria.

Which one is best for your dog? We can’t tell you that. Price or local availability influences some dog owners decisions. The most important criterion should be your dog’s response to the food. Keep an eye on his coat, eyes, ears, stool, mood, energy, appetite, and grooming habits. If he develops itchy paws, diarrhea, or goopy ears a week after changing foods, think about changing again. Note the ingredients in the brand and variety you tried, in case you begin to see a trend an intolerance of chicken, for example. But if his health improves after changing foods, you’re on the right track.

By the way, we don’t think any food should be your dog’s one and only diet for months and years. As we discussed in Variety Is the Spice of Life (WDJ June 2001), it’s a good idea to periodically switch foods. Manufacturers tend to use the same vitamin/mineral pre-mix and the same food ingredients for years and years, resulting in a product with a fairly constant nutrient content. If a dog eats the same food and nothing but that food for years and years the brand loyalty that manufacturers love to hear about any nutritional imbalances, excesses, or deficiencies present in the food can eventually affect your dog’s health.

Food allergies and intolerances can also develop in dogs who eat the same food for long periods. Changing from a chicken-based food to one that contains only beef to a fish-based food can help prevent the development of food allergies.

To reiterate: We equally like and approve of all of the foods listed among our selections, and any other foods that meet our selection criteria. But your dogs response to the food is the ultimate criterion.

To view WJD’s 2002 Canned Dog Food Review here.

Also With This Article

Click here to view “Which is the Best Type of Dog Food?

Click here to view “The Top 5 Things to Look For on a Commercial Dog Food Label”

-by Nancy Kerns

Training Dogs with Hand Signals

[Updated February 5, 2019]

Does your dog know what “Sit!” means? Most people think their dogs do, because when they stand in front of their dogs looking down at them, pointing toward the ground, and saying, “Sit! Sit! Sit!”- their dogs sit! Voila!

I would argue that, in fact, the average dog who sits in that situation does not know the verbal cue, “Sit!” What he understands is that he should sit when he is confronted by his person standing in a certain position in relation to him, with a certain expression on her face, making a certain sound. If he really understood, “Sit!” he would sit (most of the time) when he heard anyone around him, in any position or posture, say, “Sit!”

You can test my theory. Say “Sit!” to your dog when you have your back to him and are looking up at the ceiling or with your arms crossed over your chest, or when you are hopping on one foot. If he sits when you do these things, then he really does understand the verbal cue, “Sit!”

An important goal of my Level 1 training classes is to teach people to use verbal cues with their dogs. Getting the dogs to perform various behaviors by using a combination of verbal cues, body language, and lures is easy. Getting the dogs to do the behaviors without the prompts, on just a verbal cue, is more challenging, but it’s of the utmost importance. After all, there are numerous situations where you have only your voice to communicate with your dog. There are times when your hands are full – of groceries, school books, laundry baskets, the baby. There are times when your dog cannot see you; he may be behind you, in another room, or behind a tree and about to cross a road. At some time in his life he may become visually impaired, no longer able to see and respond to your body language.

I teach hand signals in my Level 2 class. My students are generally delighted when they discover how much easier it is to get their dogs to respond to distinct body language cues for specific behaviors – much easier than it is to teach verbal cues. It’s easier because dogs are primarily body language communicators, and they have a large body vocabulary. The twitch of an ear, the shift of an eye, a slight turn of the head – these are just a few canine expressions that are rich with meaning to other dogs.

I teach hand signals because there are also times when visual cues are the communication tool of choice. You may be talking to someone – on the phone or in person – and do not want to interrupt the conversation in order to ask your dog to lie down. The new baby may finally be sleeping, and you don’t want to risk waking her by talking to your dog. As your canine pal ages, he may lose his hearing and no longer be able to hear and respond to verbal cues. And you may simply love the way your relationship is enhanced when you can communicate silently with your dog.

To review: If a dog is going to be taught just one clear cue for various behaviors, I think it’s most important to teach him an auditory cue. If a person takes his training further, he should learn visual cues, too. In the best of all possible worlds, a dog should know both types of cues for almost every basic behavior you want him to perform.

In past WDJ articles, I’ve mostly discussed teaching dogs verbal cues for various behaviors. Here, I’ll concentrate on how to teach him visual cues.

Training Your Dog with Hand Signals

There are two philosophies about hand signals. Some people like to use small, subtle signals, barely visible to the human eye. A tiny finger movement cues the dog to lie down. Another elicits a sit. A small wave sends the dog into heel position. Impressive – it appears that the dog is mind-reading!

The other school of thought advises that hand signals should be BIG, so the dog can see them from far away. If you want your dog to lie down on the opposite side of a pasture, he won’t be able to see a finger flick.

I advocate teaching both. While a dog cannot learn two different behaviors for the same cue (“Down” means either lie down, or don’t jump on me – it can’t mean both), they are perfectly capable of learning two (or more) different cues for the same behavior. My Scottie knows the cue for “Down” in several languages – a result of his role as a demonstration dog in my classes. When he learned to lie down on the verbal cue “Down,” I had to use a new word in order to be able to show the class what to do when a dog does not lie down for the verbal cue. Dubhy will now lie down in English, French, German, Spanish, and in response to a hand signal.

To teach your dog a new cue for a behavior that he already knows how to perform, first decide what your new cue is going to be. Pick a discrete motion that you can replicate easily; consistency is the name of the game here. Your dog will learn to associate the new signal with the old signal more quickly if the new signal looks the same each time.

Now begin working with the two signals together. Give the new cue (hand signal) a second or two before the cue that he already knows, until he begins to anticipate the second cue upon seeing the first. “Mark” his behavior the moment he does the right thing (I strongly recommend using a clicker or a verbal marker, such as the word “Yes!”) and then give him a tasty reward. This sequence, in essence, tells your dog, “This new cue means the same thing as the old cue.”

How to Start Using Silent Cues

Here is how I initially teach hand signals for Down, Sit, and Come. I encourage my students to start with big hand signals, like the ones most people use in obedience competitions. No one wants to risk having their dog miss the signal from across the ring!

• Down: Hold a treat in your right hand. With your dog sitting in front of you, stand with both arms relaxed at your sides. Raise your right arm straight up. A second after your arm reaches its full height, fingers pointed toward the ceiling, say your verbal “Down” cue. Pause for another second. If your dog does not lie down, lower your right hand to his nose and lure him down with the treat. Click! (or “Yes!”) and treat. Repeat this exercise until he will lie down for the hand signal and verbal cue without the lure.

When he has done at least a half dozen downs without the lure, give the hand signal (arm raised) without the verbal cue. If he goes down, Click! and Jackpot! That is, feed him lots of treats, one at a time, in special recognition of his accomplishment. If he doesn’t lie down, do another dozen repetitions with both cues, and then try again with just the hand signal. You will probably be surprised by how quickly he does it.

Say you are talking on the phone with your boss and your dog starts barking playfully at your cat. A finger held to your lips can be used to tell your dog to “Shush.” But if that caller is someone you don’t want to talk to, you can also use a signal (Sandi rapidly opens and closes her hand) to ask your dog to bark like mad, then excuse yourself to “go catch that dog

• Sit: Hold a treat in your left hand this time. With your dog lying down in front of you, stand with both arms relaxed at your sides. Bring your left arm up in a circular motion in front of your chest with your elbow bent, then straighten it out to your left side, parallel to the ground, in a “ta-da!” sort of flourish.

A second after your arm straightens, say your verbal “Sit” cue. Pause for another second. If your dog does not sit, bring your arm down and lure him up with the treat in your hand. Click! (or “Yes!”) and treat. Repeat until he will sit for just the hand signal and verbal cue without the lure.

When he has done at least a half dozen sits without the lure, give the hand signal (arm raised) without the verbal cue. If he sits, Click! and Jackpot! If he doesn’t, do another dozen repetitions with both cues, and then try again with just the hand signal. Keep repeating until he gets it. Then practice this from the “Stand” position as well.

• Come: If your dog is well trained, you can leave him on a sit- or down-stay and walk five feet away. If his stay is not rock-solid, have someone hold him on a leash while you walk away.

Turn and face him, with your arms at your sides and a treat in your right hand. Fling your right arm up and out to your side, as if you wanted to smack someone standing behind you. A second after your arm is out and parallel to the ground, say your verbal “Come!” cue. If he does not come, hold your arm parallel to the ground for another second, then bend your elbow and sweep the treat past his nose, ending up with your hand in front of your chest. If necessary, take a step or two back to encourage your dog to get up and come to you. Repeat this exercise until he will come for the hand signal and verbal cue without the lure.

When he has done at least six or so recalls without the lure, give the hand signal without the verbal cue. If he comes, Click! and Jackpot! If he doesn’t, do another dozen repetitions with both cues, and then try again with just the hand signal. When he starts responding, begin practicing the hand-signal “Come” from increasingly greater distances.

Subtle Hand Signals

You may need to approach the task of teaching tiny cues a little differently. Because a lot of our moving and twitching is not meaningful communication for our dogs, they learn to tune out or ignore most of our small movements, unless we take the time to teach them that a particular small movement has meaning. You may have to start with bigger signals and gradually shrink them down to “mind-reading” size.

• Down: If you train using positive methods, you probably taught your dog to lie down by moving a treat or toy lure toward the floor in front of his nose. He already knows that your hand moving toward the floor is a cue for “Down.” You can teach him a finger-point “Down” by gradually reducing the motion you have been using, but without the lure, until it morphs into a finger point. Or, if you have dog who is very observant, you can simply start with the finger point. In either case, give the signal, give him a second to respond, then say your verbal “Down” cue, and finally, lure him down if necessary. Click! and treat.

• Sit: Similarly, you may have taught your dog to sit from the down position by luring him up with a treat. It’s easy to turn your lure motion into a small upward finger twitch, the same way you did with the “Down” cue. Either gradually shrink the lure motion until it becomes tiny, or start right in with the final motion that you want to use. Remember the sequence: hand signal, then verbal cue, then lure if necessary. Remember to Click! and treat.

• Come: You probably don’t need to lure your dog to teach him to come – you more likely used body language such as moving backward to encourage him to come running to you. Give him a small hand signal such as holding your hand with your palm facing your stomach and beckoning to him with all four fingers. A second later, give your verbal “Come” cue and take a step backward if necessary. Of course, Click! and reward him when he comes. He’ll probably get this one very quickly!

Remember that in order for you to be able to communicate with your dog nonverbally, he has to be looking at you. You may want to teach him a nonverbal “pay attention” cue such as a finger snap, so you can get him to focus on you without interrupting your phone conversation. Just pair that snap with a tasty treat (snap, and then feed him a treat) and he’ll be happy to look at you when he hears that sound.

Also remember that you don’t need to limit yourself to hand signals. Any part of your body can cue a behavior. You could teach your dog to lie down when you duck your chin toward your chest, or tap your foot on the floor. You could teach him to come when you shrug your shoulders, or to sit when you raise your eyebrows. Just follow the three-step process to teach any signal for any behavior: Give the signal you have chosen for the behavior, say the verbal cue, then lure if necessary.

Hand Signals for the Deaf or Hearing-Impaired Dog

Hand signals are an obvious training tool for deaf dogs. Lure and reward training is also a natural for deaf dogs – they will follow your hot dog treat just as easily as any other dog.

Click! or verbal marker such as

“Yes!”

The difference is that you must use a visual reward marker rather than an audible one. Instead of a Click! or a “Yes!” to mark the rewardable behavior (followed by a treat), do something that your dog can see – such as a “thumbs-up” sign – and follow it with a treat. Some trainers recommend a hand “flash” – a closed fist rapidly opened with all fingers extended – as a highly visible deaf “Click!”

Once your dog understands that a juicy piece of hot dog always follows the hand flash, he will be able to learn that whatever he is doing when he sees the hand flash has earned him a reward. He will then offer that behavior more often, in hopes of winning a hand flash and treat.

As long as you remember to signal and reward – very frequently at first, then with reduced frequency later on, if you wish, he will do appropriate behaviors, such as sitting to greet you, easily and consistently.

Training “regular” dogs to respond to verbal cues alone can be challenging. With a deaf dog, you never have to worry about that; you will depend on visual cues only to communicate with your dog and elicit the desired behavior responses.

While some deaf dog advocates recommend learning American Sign Language as used with hearing-impaired humans and using that with your dog, it isn’t necessary. You just need to create a set of clear hand signals for the behaviors you want to teach your dog, and be consistent in how you use them.

Just like words, visual signals mean absolutely nothing to your dog until you associate them with a behavior. Whatever signals you use, be sure to be patient and positive, and take the time your dog needs to help him understand what they mean. Punishing him for not responding will only confuse and frighten him.

TRAINING WITH HAND SIGNALS: OVERVIEW

1. Think about which behaviors you would like your dog to perform without an audible cue. Make up a discrete physical cue for each behavior. Be creative!

2. Teach your dog each visual cue in this order: Use the new cue, wait a second; use the old verbal cue, wait a second; and then lure the behavior, if necessary. Reward him for each success.

3. Be cheerful and patient and make sure your cues are consistent. Your dog will quickly learn to anticipate the old cue after seeing the new one, and begin offering the desired behavior after the new cue only.

Pat Miller, WDJ’s Training Editor, is also a freelance author and Certified Pet Dog Trainer in Chattanooga, Tennessee. She has served as the president of the Board of Directors of the Association of Pet Dog Trainers and is author of The Power of Positive Dog Training.

Thanks to Sandi Thompson of Sirius Puppy Training in Berkeley, California, for demonstrating hand signals for our camera.

Clean Teeth, Healthy Dogs

Everyone likes to see a beaming, white smile. Perhaps we’re hard-wired to be attracted to those beings radiating health and vigor. Subconsciously, maybe, we understand that clean, strong teeth reflect youth, a robust immune system, and a well-nourished body.

In dogs, that healthy white “smile” is especially significant as an indicator of overall health and function. Dogs use their mouths not only to eat and drink, but also to communicate, groom, play, and socialize. A healthy mouth is vital for adequate performance of all these roles.

Plaque and tartar accumulate on canine teeth just like ours. Plaque is made of proteins from saliva, which interact with bacteria. If left to accumulate on teeth, bacteria quickly multiply and can invade the gums around the teeth, causing inflammation known as gingivitis. If plaque is not removed, inflammation of the gums can spread to the bone around the teeth, leading in turn to bone loss or periodontal disease. Without adequate bony support, teeth may become loose, or even fall out.

Tartar, or calculus, forms when minerals from saliva cause plaque on the teeth to harden. For older dogs and small dogs with small teeth, plaque accumulation and subsequent disease can progress quickly.

Poor oral health poses more than just a social problem for its canine victims; it may also contribute to poor overall health. “There are clear indications that oral health status has a far reaching effect on an animal’s general health,” says Dr. Frank Verstraete, clinician at the Dentistry and Oral Surgery Service at the University of California, Davis Veterinary Medical Teaching Hospital (VMTH). “Periodontal disease may cause bacteria and toxins to enter the bloodstream with potentially negative effects on internal organs. On the flip side, poor systemic health may manifest in the oral cavity in various ways, and exacerbate periodontal disease.” Veterinarians often find that chronically ill dogs quickly improve after professional dental cleaning and resolution of oral infections.

Frequent exams