[Updated January 10, 2019]

PREDATORY DRIVE OVERVIEW

1. Make a reasonable assessment of your dog’s level of predatory behavior, and manage his environment accordingly.

2. Diligently practice training exercises that will specifically address the chase behavior challenges that your dog is likely to present to you. Provide him with appropriate outlets for his predatory/chase behaviors.

3. Don’t ever allow him to be placed in a situation where his predatory instincts can threaten the life of another human, especially a child. You risk his life, too, if you do.

Tiffany approached me shortly before the start of her weekly training class recently, clearly distraught. “Newton did something very bad this week,” she said.

My heart skipped a beat as I glanced down at Newton, the black and white Border Collie/Basset mix sitting calmly by her side. In my dog trainer brain, “very bad” usually equates with serious aggression to humans. Newton and his vivacious, committed owner are two of my favorite clients, and I didn’t want to hear that Newton had done something irredeemable.

“What did he do?” I asked.

“He chased and killed a bunny in my backyard!” Tiffany wailed. “My roommates and I were so upset. He dropped it immediately when I told him to, but it was too late, the bunny was dead!”

I breathed a silent sigh of relief, and reassured her that while I understood her distress, Newton’s behavior was natural and normal. Bassets were bred to chase rabbits, after all, and Border Collies were bred to chase things that move. More often than not when our dogs chase small beings like squirrels and rabbits, the little critters manage to escape. This poor bunny wasn’t so lucky, and Newton just did what dogs do.

Canine Predatory Instinct: Is It Aggression?

Our dogs’ predatory instincts are one of the things that makes them fun to play with. When you throw a ball or a stick and he chases it, you are triggering his natural predatory desire to chase things that move. In fact, some behaviorists argue that predatory behavior should not be called aggression at all – that it is more appropriately interpreted as a form of food-getting behavior.

Indeed, the motivation to chase prey objects is vastly different from other forms of aggression, which are based on competition for resources and/or self-protection. It is distinguished from other forms of aggression by a marked absence of “affective arousal” (anger), and is a social survival behavior, not a social conflict behavior. Predatory behavior is indicated by distinct behaviors: hunting (sniffing, tracking, searching, scanning, or waiting for prey); stalking; the attack sequence (chase, pounce/catch, shaking kill, choking kill); and post-kill consuming. The underlying motivation for chasing things that move is to eat them.

Dogs who challenge, bark, snarl, and chase skateboarders or joggers who pass the house are generally believed to be engaging in territorial aggression – individual predators don’t usually openly advertise their intent by making lots of noise (although anyone who has ever followed a pack of baying hounds knows that group hunting can be quite noisy!). Dogs who hide in ditches or behind bushes and silently launch their attack on unsuspecting passers-by are exhibiting more classic predator behavior. However, the frustration of restraint on a chain or behind a fence combined with constant exposure to the trigger of rapidly moving prey objects can push a dog from predatory behavior to real aggression. Both behaviors, of course, are dangerous.

Just because predatory behavior is natural doesn’t mean that it’s acceptable in its inappropriate manifestations. It was not acceptable to Tiffany and her roommates for Newton to chase and kill a bunny, and it certainly wasn’t acceptable to the rabbit. Predatory behavior has been responsible for the death of many unfortunate pet cats, rabbits, chickens, sheep, goats, and other livestock, and even humans. While it often can be expressed in harmless, even useful outlets such as games of fetch, retrieving ducks, and herding sheep, chase behavior can be dangerous to dog and prey alike. It is our responsibility, as caretakers for our canine companions, to be sure their natural predatory instincts don’t get them into trouble.

It’s in the Genes

It should come as no surprise that some breeds seem to have a much stronger predatory instinct than others. Dogs who were purposely bred over the centuries to chase and kill small animals are much more likely candidates for strong chase behavior than those with enhanced genes for lap-sitting. While there are exceptions in every breed and group, and any individual dog from Chihuahuas to Newfoundlands can display predatory behavior – or not; in general the following dogs are exceptionally likely to display strong predatory behavior:

■ Herding breeds (such as Border Collies, Kelpies, Australian Shepherds, Cattle Dogs, etc.)

■ Sporting breeds (Retrievers, Spaniels, Setters, Pointers, etc.)

■ Hounds (Beagles, Bassets, Bloodhounds, Coonhounds, Greyhounds, Salukis, etc.)

■ Terriers (Jack Russells, Scotties, Westies, Rat Terriers, Bull Terriers, etc.,)

■ Northern breeds (Huskies, Malamutes, etc.)

■ Wolf hybrids

Interestingly, because of the specialized purposes for which these dogs have been bred, many of these breeds will display parts of the predatory sequence of behaviors more strongly than others. The herding breeds have a strong stalk and chase behavior, but the kill-and-consume part of the sequence has been greatly inhibited. Sporting breeds are strong on sniffing, scanning, watching, and grabbing, but again, have been bred not to actually destroy the prey – they are supposed to gently bring it back.

The hounds are split into two groups. The scent hounds are built low to the ground, with long ears to catch scent particles. These dogs are very big on the sniffing and chasing aspects of the sequence. They may sometimes actually catch and kill, but it’s not their primary purpose. The sight hounds, on the other hand, are long-legged to enhance their ability to scan – to look for prey rather than finding it by smell – and to run after it, fast, when they see it.

Terriers have had the grab-and-kill part of the predatory sequence genetically enhanced, giving them a well-deserved reputation for a pugnacious personality. Their owners didn’t just want them to find the rats in the barn; they really wanted the dogs to kill the rats. Or, historically, in the sad case of the Pit Bull Terrier, people wanted the fighting Terriers to kill any opposing dog.

The Northern breeds have been the least genetically manipulated, which is why, in part, they most closely resemble their wolf ancestors. Thus they, and the unfortunate Wolf hybrid, are most likely to display the complete predatory sequence.

Manage Your Predator

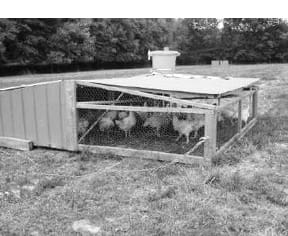

As with so many other undesirable dog behaviors, if your dog has a strong prey drive, your first line of defense is management. Make sure you have a secure fence from which your dog cannot escape. Don’t leave him in the yard unattended if he will be constantly tantalized by lots of fast-moving prey objects, such as squirrels, deer, skateboarders, small children running and playing.

Use leashes and long lines to prevent your dog from taking off after deer, rabbits, and squirrels when you are on walks and hikes. Especially keep him on leash at dawn and dusk, when the deer and the antelope – and other small, wild things – are most likely to play. Look for ways to minimize his visual and physical access to prey in his own yard – a solid fence will prevent him from seeing things moving quickly by, and will prevent many potential prey animals (including small children) from entering easily. A non-visible underground electronic fence will not. Nor will a non-visible fence necessarily prevent him from leaving the yard if he is highly motivated to chase prey.

A muzzle can also be useful on a limited basis. Since muzzles restrict a dog’s ability to drink water and pant normally, you cannot leave one on your dog while you are away all day at work. But if he’s devastating the squirrel population in your backyard, or you want to give a litter of baby bunnies a chance to grow up and get wiser and faster, you can put a muzzle on him for brief fresh air/potty trips to the yard. Be sure to take time to desensitize him to wearing a muzzle first, by associating it with yummy treats while you put it on him for gradually longer periods of time.

Training for Instinct

You will never train most herding dogs not to chase things that move, given the chance. Similarly, you’d be hard pressed to convince many terriers not to go after rats and other small creatures when the opportunity arises. Their brains are hardwired to chase, and you can’t change that.

A slightly less imposing goal is to change the predatory response into an incompatible behavior response. For example, you could teach your Border Collie that the appearance of a deer is the cue to lie down. She can’t “down” and “chase the deer” at the same time. Or, as we taught our own Scottie, the appearance of your kitten could be the cue for your dog to sit at your feet. This type of training can be difficult because the dogs are so highly motivated to chase – it is quite a challenge to convince them that they’d rather do something else. You must find something highly rewarding in order to make it work. For our Scottie, it was food. For a Border Collie, it might be the opportunity to chase a tennis ball – after she lies down – instead of the deer.

This approach works best in your presence, and only if you practice it regularly rather than just expecting it to work in the heat of the moment. Although we are quite comfortable leaving our now-grown kitten alone with Dubhy, it was several months and several pounds worth of kitten-growth before we stopped shutting her in her own room when we weren’t there to supervise. You might not ever be able to expect that your Border Collie will leave the deer (or the skateboarders) alone if she is outside, unrestrained, and left to her own devices.

A solid foundation of good manners training can also be helpful, combined with vigilance on your part. If you are out hiking with Bess and see the deer before she does, you can call her to you and snap the leash on. Even if she sees it first, a really reliable recall will bring her back to your side, especially if you call her pre-launch, before she is headed hell-bent-for-leather after the fleeing deer.

A well-trained emergency “Down!” can also save the day, even if your dog is in full stride. Many dogs will “Down!” even when they won’t “Come!” because they can still watch the prey. Stopping the charge gives the dog’s arousal level and adrenaline time to recede, and you may be able to call her back from the “down” or calmly walk up to her and snap her leash on her collar.

Dangers of Thwarting

Dogs who have strong, hardwired behaviors are usually happiest if they are allowed to engage in those behaviors in some form. Greyhounds chase mechanical rabbits on the track – and while we abhor the abuse that is rampant in the Greyhound industry, there is no question that the dogs love to run and chase. Jack Russell Terriers are in heaven when they get to play in Earthdog trials. Our Australian Kelpie, Katie, gets a huge charge out of running circles around our horses in the pasture, even though they are impervious to her attempts to direct their movement.

In fact, if hardwired behaviors are constantly thwarted (prevented from occurring), you risk having your dog develop compulsive disorders. A canine compulsive disorder (CCD) is a normal coping behavior that becomes exaggerated to the degree that it is harmful to the dog. Some common examples are excessive licking, spinning, and tail-chasing. Some dogs are genetically predisposed to CCD, but it usually takes an environmental trigger – stress – to cause the behavior to erupt. The breeds known to have a high prey drive (see sidebar, “It’s in the Genes”) are often the most susceptible to developing stereotypical spinning behavior when kept in high-stress kennel environments.

If you are the owner of a dog with strong predatory inclinations, it behooves you both to find an outlet for the behavior rather than simply trying to shut it off. Encourage your dog to chase and fetch balls, sticks, and toys, and take the time to engage in several fetch sessions with him per day.

Use these strong reinforcers to incorporate training in your play sessions and strengthen your dog’s good manners. If your dog rudely jumps up and tries to grab the Frisbee from your hand, whisk it behind your back until he sits, then bring it out again, and only throw it if he remains sitting until you throw. You are using two of the four principles of operant conditioning here. The dog’s behavior – jumping up – makes the Frisbee go away, which is “negative punishment” – the dog’s behavior makes a good thing go away. When he sits and stays sitting, you throw the Frisbee. This is “positive reinforcement” – the dog’s behavior makes a good thing happen. Works like a charm.

If you have a Terrier, provide an outlet for his prey-seeking behavior by creating a digging spot – a box filled with soft soil or an area you have dug up where he is allowed to dig. Bury his favorite toys and encourage him to “Find it!” Toys that squeak and wiggle are especially suited to Terrier games.

Come Chase with Me!

One of the most useful applications of chase behavior is in conjunction with teaching your dog to come when called. Lots of dog owners make the mistake of moving toward their dogs – or even chasing after them – when they won’t come. In dog language, a direct frontal approach is assertive, even aggressive, and dogs naturally move away from it.

It’s much more effective to do the exact opposite – run away from your dog! Start playing chase/recall games when your dog is a pup. Get excited, call your pup, and run a short distance away. Let him catch up to you while you are still facing away from him, then turn sideways, kneel down (don’t bend over him), praise him, feed him a treat or play with a tug or fetch toy, and pet him (if he enjoys being petted; not all dogs do). If your dog is no longer a pup, you can still play this game to strengthen his response to the Come! cue.

Teach your dog from early on that “Come!” means “Chase me and play,” keep up the games as he matures, manage him so he doesn’t get to practice inappropriate predatory behavior, and find acceptable outlets for his natural chase behaviors. Using these tactics, you’ll have a much better chance of getting those incompatible behaviors later on when you are faced with the challenge of competition from real prey.

What About the Baby?

One of the very real concerns I hear expressed from new or soon-to-be parents is that of the family dog’s predatory behavior being elicited by the baby. There is some evidence to support the belief that at least some dogs may view an infant more as a prey object than as a little human. New babies move strangely, and make funny noises that can resemble prey distress sounds.

The Centers for Disease Control in Atlanta, Georgia, published figures from the 25 dog bite-related fatalities in the two-year period from 1995 through 1996. Of those 25 deaths, 20 of the victims were children (80 percent). Three of the children were less than 30 days old, one was under five months, and 10 were from one to four years old. The remaining six child victims were under 11 years old.

It is likely that the three neonates and perhaps the five-month- old baby were victims of prey-related behavior, while the others were at least as likely to have somehow elicited a true social conflict/aggression attack.

I strongly recommend that all parents-to-be, but especially owners of dogs with strong predatory behavior who plan to bring an infant into the home, work with a trainer/behaviorist to desensitize the dog to the sights and sounds of a baby, and to create a good training and management plan to ensure that Fido and Junior will be comfortable with each other.

There are CDs and audio tapes of baby noises available to help with this process, which can be used to teach the dog that a baby’s cries are the cue to lie down on his bed – or do a Lassie trick and go get Mom or Dad.

It goes without saying that dogs should never be left alone with infants and young children, but that warning goes triple for dogs who have demonstrated any propensity toward predatory behavior. A family dog mauling or killing a child is a horrible tragedy that just doesn’t have to happen.

Note: “Sound Sensibilities: Babies CD” is an excellent desensitization resource created by dog trainer Terry Ryan.