The rescued puppy has diarrhea, gummy eyes, ear mites, and ringworm, but there’s a spark in his eye and his tail is wagging. A stray dog has an upper respiratory infection, skin lesions and worms, yet the person who finds her knows she’ll make a loyal companion.

Some of the best dogs come into our lives in damaged condition, and the right support can transform them. Yet when dogs have multiple problems, it’s hard to know what to do first. Many dogs and puppies in pet stores, animal shelters, or on the street suffer from malnutrition and conditions that take advantage of impaired immunity; parasites, bacterial infections, fungi, and viruses all take their toll.

Not only neglected or starving dogs suffer from a lack of wholesome, nutritious food, causing and prolonging illness; there are numerous dogs whose food bowls are filled with kibble daily who nonetheless exhibit signs of nutritional deficiencies. A dog who eats nothing but low-quality, generic, and/or “grocery store” type foods – which may not contain quality ingredients with bio-available nutrients – may develop chronic conditions relating to his undernourished condition.

Most holistic veterinarians believe that improving the diet of these chronically ill dogs – and dogs who suffer from multiple ailments – is critical to restoring these dogs to health. Moreover, the use of certain supplements can significantly boost the dog’s ability to heal himself. Below, we’ll describe the most commonly used, effective nutritional approaches for quickly improving a dog’s health and vitality.

First things first

If you’ve brought a raggedy stray dog or a beleaguered shelter dog into your home and heart, you’ll want to address some of his most obvious problems immediately; not many of us could or would wait for improved nutrition and health to heal a dog’s minor cuts or abrasions, infections, or parasite infestations, even though these things generally will eventually resolve if a dog is fed and supplemented correctly. However, some gentle treatments can be employed right away to make the dog more comfortable – and help you be more comfortable around him!

When taking a holistic approach to health, we don’t generally employ the use of powerful antibiotics and antibacterials for minor conditions. Instead, we use mild treatments that work synergistically with the body. For example, minor cuts, abrasions, hot spots, and skin lesions can be doused with strong antibacterial solutions – such as iodine-based soaps, topical antibiotic ointments, or alcohol-based rinses – which will help kill bacteria. But these preparations can also kill healthy tissue and the dog’s own pathogen-fighting cells in a sort of scorched-earth manner. Many dog owners have found less forceful preparations to be just as effective – and less insulting to the body’s own defenders. Most minor external injuries can be cleaned with liberal applications of aloe vera juice or gel with perfect results.

Similarly, don’t automatically turn to pesticides to control parasites; these preparations can burden the dog’s already overworked toxin-removal system. To treat ear mites, swab the dog’s ears with a cotton ball saturated with pure mineral oil every two or three days for three weeks. Mineral oil, which has large molecules, smothers the mites. Clean the ears with cotton or tissues before reapplying the oil. Remove fleas with a gentle shampoo and nontoxic flea control products; comb the dog daily with a fine-toothed flea-comb and you will note a steadily decreasing population of the pests. Frequently vacuum your house thoroughly (to remove any flea eggs) and wash the dog’s bedding (to destroy flea eggs) to help prevent reinfestation.

In short, do what you can to make the animal clean and comfortable, without causing any new problems. And make an appointment as soon as possible with your holistic veterinarian for an overall health check.

Food first; then supplements

An important step in any dog’s recovery is the right diet. Dogs are designed to eat a variety of fresh, whole foods, and a balanced, raw, home-prepared diet is an excellent way to provide the nutrients they need to heal from the inside out.

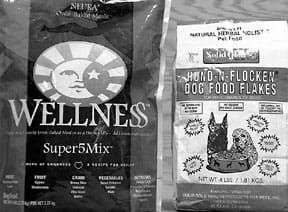

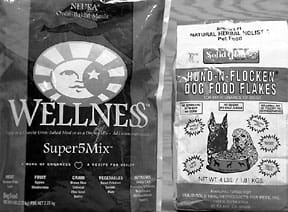

For those who aren’t able to feed Fido from scratch, buy the best commercial dog food you can find and afford . . . and then improve on it. (See “The Best Dry Dog Foods,” WDJ February 2001, “Canned Answers,” WDJ October 2000, and “Food in the Freezer,” WDJ March 2000.)

Fresh juice and raw liver are some of the healthiest foods you can add to your dog’s diet. If you have a juicer, use it. Most dogs and puppies love carrot juice, which contains abundant zinc, vitamin E, copper, beta carotene, and other nutrients that strengthen immunity. For best results, use organically grown carrots and add a handful of celery, parsley, or apple as desired. Feed directly if your dog likes it (most do) or start with small amounts in food. Try to feed 1/2 cup fresh juice per 25-30 pounds of body weight per day.

An easy way to make fresh, raw carrot juice even more nutritious is to add raw liver. Some veterinarians call liver a miracle food for its ability to save lives and improve health. I’ve heard of newborn puppies who were dying of Fading Puppy Syndrome come back to life as soon as a tablespoon of chopped liver was added to their mothers’ diet. Bottle-fed orphan pups suddenly grow and gain weight when pureed liver is added to their formula, and dogs with injuries and serious illnesses heal faster when liver is added to their food.

Raw beef and chicken liver are rich in protein, amino acids, phosphorus, potassium, copper, vitamin A, and B-complex vitamins including folic acid, pantothenic acid, vitamin B6 and choline. Because the liver stores toxins, feed liver only from organically raised poultry and cattle.

To help sick dogs and puppies, feed small amounts, such as one teaspoon raw organic calf or chicken liver per 10 to 20 pounds of body weight, once or twice per day.

Support supplements

When a dog or puppy has multiple problems, it’s tempting to try every supplement that might help. With thousands of products on the market, deciding what to buy can be daunting.

“I would start with digestive enzymes, colostrum, and acidophilus to try to get the natural flora going again,” says Beverly Cappel, DVM, a holistic veterinarian in Chestnut Ridge, NY. “In addition you can give superoxide dismutase (DOS), B vitamins, vitamin C, and echinacea-goldenseal tincture to help fight infection. Puppies need only a drop or two of tincture, and depending on size, adult dogs can take up to 10-15 drops a day. You don’t want to overdo it by giving too many supplements or too much of anything, because when dogs or puppies are seriously weak, that can push them over the edge. Keep them warm and dry, make sure they’re eating, and make sure they’re hydrated.

“If drugs are needed, use drugs. Some animals have such acute infections that antibiotics save their lives, but in many cases, all they need is tender loving care and the right nourishment.

“I tell people to use common sense and treat sick puppies the way they would an infant or young child. Keep them warm, dry, well fed, and well watered, and give them any product that supports the immune system.”

Enzymes

Enzymes are proteins that, in small amounts, speed the rate of biological reactions such as digestion. Nearly every raw food carries within it the enzymes necessary for its digestion, but cooking inactivates these enzymes and the body must work hard to replace them in order for food to be broken down and assimilated.

Digestive enzymes such as pancreatin and bromelain help replace enzymes destroyed by heat. Enzyme supplements given between meals on an empty stomach help dogs recover from illness and injury. Enzyme powders mixed with food improve its digestion and assimilation. Even dogs on an all-raw diet, which contains abundant enzymes, can benefit from these supplements when ill or recovering from illness. (For more information about systemic oral enzyme therapy, see “Banking on Enzymes,” WDJ January 2001.)

Colostrum and lactoferrin

Colostrum is the first milk a mammal produces after giving birth. In dogs, cows, and humans, this milk is so rich in immune system support that it protects newborns from infections and intestinal disorders. Colostrum affects 32 growth factors including muscle, cartilage, connective tissue, body weight, and lean muscle.

Colostrum and lactoferrin protect the mucous membrane, interfere with the reproduction of harmful bacteria, activate T-cells which attack invading organisms, repair damaged muscle and cartilage tissue, and improve muscle tone. They are recommended for any animal that is weak, elderly, susceptible to illness, and fighting or recovering from any disease.

Colostrum supplements derived from cows’ milk are reported to enhance immune function in dogs and kittens. Lactoferrin, one of the immune factors in colostrum, is also sold as an immune-enhancing supplement.

Probiotics and prebiotics

A probiotic supplement, like live-culture yogurt or acidophilus, contains beneficial bacteria that help fight infection while improving digestion. Prebiotic supplements actually nourish the beneficial bacteria. Together, prebiotics and probiotics help replace beneficial bacteria destroyed by antibiotics or an inadequate diet.

Powdered acidophilus and similar probiotics can be added to food or mixed with water. Check your health food store’s refrigerator for the freshest supplements.

Sweet whey (not to be confused with whey protein) is a by-product of cheese-making and the clear liquid that separates from yogurt when you strain it through cheesecloth. This important prebiotic feeds the beneficial bacteria in your dog’s digestive tract. If fresh whey is not available, powdered sweet whey can be added to food or water; in fact, most dogs like the taste, so adding sweet whey to water encourages them to drink more. Start with small amounts, such as 1/8 teaspoon per 20 pounds of body weight twice a day, to be sure the dog tolerates it well. Giving the milk-digesting enzyme lactase at the same time can help prevent indigestion or, if the dog has trouble with whey, use a different prebiotic.

The Jerusalem artichoke is a potato-like tuber of the sunflower family, and in Europe and Japan, Jerusalem artichoke flour is added to bread, pasta, and other foods to improve digestion and feed beneficial bacteria. Inuflora is made from Jerusalem artichoke tubers that are juiced, then dehydrated. This sweet powder, produced in Germany, has been extensively tested in farm animals. According to Monika Kreuger, DVM, rector at the University of Leipzig, professor of veterinary medicine and chief of the Institute of Bacteriology and Microbiology, Inuflora also inhibits enzymatic reactions stimulated by harmful bacteria, reducing the animal’s susceptibility to infection.

Vitamins and minerals

Dogs that have multiple infections will especially benefit from supplemental vitamins and minerals. There are many multi-vitamin/mineral supplements on the market, but many holistic veterinarians prefer to use vitamin/mineral products made from whole-food sources, such as Catalyn from Standard Process or similar products from Wysong. Food-source supplements are so easily assimilated and free from adverse side effects that precision dosing isn’t necessary. Use label recommendations for guidance, but know varying dosages, such as those consumed by wild canines, won’t hurt your dog.

Although dogs produce their own vitamin C, they can benefit from extra C when ill or under stress. In his book How to Have a Healthier Dog, Wendell Belfield, DVM, documents vitamin C’s ability to improve immunity, treat viral and bacterial infections, detoxify the body, improve collagen, and improve the condition of cancer patients. He also dispels the myth that large quantities of vitamin C can be toxic or cause kidney stones. Too much vitamin C can cause loose stools or diarrhea. If that happens, reduce the dosage.

For best results, use a natural vitamin C complex that includes bioflavonoids. Any dog being treated for multiple infections can use 500-3000 mg. or more per day, depending on size and condition, in divided doses. Open capsules or crush tablets and mix the powder with food. Pediatric vitamin C drops are appropriate for pups, but as soon as possible, replace synthetic vitamin C with vitamin C from whole-food sources, such as Wysong’s Food C. As the dog’s condition improves, reduce vitamin C to maintenance doses based on label directions. Even small amounts of vitamin C make a difference if the C is from whole-food sources.

Vitamin E improves heart health, strengthens the immune system, protects the body from toxins, helps heal skin lesions, improves the effectiveness of other vitamins and minerals, and has a rejuvenating effect on older dogs.

Dr. Belfield recommends up to 100 International Units (IUs) per day for small dogs, 200 IU for medium, 400 IU for large, and 600 IU for giant breeds. Use a natural vitamin E such as Carlson Labs’ E-Gems. Prick a capsule and squeeze a small amount into food or into the dog’s mouth.

Vitamins D and A work together with vitamin E to boost immunity and fight infection. Cod liver oil is rich in both D and A, but too much of either can be toxic, so don’t overdose. Dr. Belfield recommends 100-400 IU vitamin D and 1500-7500 IU vitamin A, depending on the dog’s size and activity level. Check product labels to verify vitamin D and vitamin A levels.

Amino acids

Amino acids are the building blocks of proteins needed to construct every cell of every organ, bone, and fluid in the body. For optimum health, essential amino acids must be provided in the proper balance.

One excellent whole-food source of amino acids is the supplement Seacure, which is made from fermented deep-sea fish. In addition to helping dogs recover from illness, Seacure speeds wound healing and aids detoxification. It is especially helpful for recently weaned puppies. Most dogs love its strong fishy odor. Add to food or mix with water and give puppies one capsule three or four times per day (use a syringe or eyedropper to feed puppies as needed), or two capsules three or four times per day for adult dogs. Continue this dosage until the dog is completely well, then give one or two capsules per day for one or two months.

Gelatin

Gelatin, a jellylike substance formed when tendons, ligaments, and bones containing the protein collagen are boiled in water, is most familiar in fruit-flavored desserts. But the beneficial effects of plain gelatin are well documented in medical literature.

When taken with food, gelatin acts as an aid to digestion. It has been successfully used in the treatment of many human intestinal disorders, including colitis and Crohn’s disease. Although gelatin is not a complete protein, containing only the amino acids arginine and glycine in large amounts, it acts as a protein sparer, allowing the body to more fully utilize the complete proteins in foods eaten at the same time. Gelatin is also of use in treating many chronic disorders, including anemia, diabetes, and cancer.

Home-prepared gelatin-rich broths are easy to make by soaking bones and vegetables in cold water for an hour with two tablespoons vinegar per quart of water, then simmering over low heat for 24 hours. Generous amounts can be added to any pet’s food during and after convalescence. Alternatively, mix powdered gelatin with a small amount of cold water and add to meat, poultry, eggs, and other high-protein foods.

Stabilized rice bran

Approximately 65 percent of the nutrients in rice are in the bran, the seed coat or polish that covers the white interior kernel. Millions of metric tons of rice bran are discarded annually, unfit for human consumption because it spoils so quickly. Within a few hours of milling, rice bran’s fragile oils go rancid.

In India, where polished rice is a staple grain, fresh rice bran from the mill floor is a folk remedy that has long been used to treat illnesses in adults and children. Rice bran is rich in vitamin E, antioxidants, plant sterols, amino acids, trace minerals, fiber, B vitamins and other phytonutrients that are easily assimilated and work synergistically to restore good health.

In the 1980s, USDA researchers in California discovered a method for deactivating the lipase enzyme and stabilizing the oils in rice bran, preventing rancidity and giving the bran a long shelf life. It has been used in animal feeds ever since, and according to Betty Kamen, PhD, the benefits to companion animals and horses include improvement in joints and connective tissue, skin and coat disorders, metabolism, immune system function, stamina, cell protection, and stable blood sugar. “Another animal health application is the positive effect of rice bran on canine digestion,” she says, “especially after bouts of gastroenteritis. The fiber and digestive coenzymes in rice bran are said to bring about a natural calming effect in the digestive system.”

Dog owners and breeders using stabilized rice bran report increased vitality, reduced shedding, and improved endurance.

Garlic

Many culinary herbs have medicinal uses, but garlic is both the most widely used and the most researched. Garlic is rich in sulfur compounds and volatile oils. It fights infection, helps prevent cancer, expels tapeworms, inhibits protozoan infections such as Giardia lamblia, makes animals less attractive hosts to fleas and other parasites, and prevents blood clotting.

Garlic’s odor can be offensive, but several companies produce odorless garlic products. Dr. Belfield describes how some breeders prevent roundworms and other parasites by giving each dog and puppy one garlic-parsley tablet per day. Alternatively, grind, chop, or finely mince fresh garlic and parsley together and add one-quarter-teaspoon per 10 pounds of body weight to food.

Retired veterinarian Gloria Dodd, DVM, endorses Kyolic brand aged garlic extract and gives it to all her animals as well as to herself and her family every day. When a new strain of parvovirus that causes severe hemorrhagic gastroenteritis struck her California valley, most of the infected dogs died from acute toxemia despite prompt veterinary treatment. By adding Kyolic to her protocol, Dr. Dodd was able to save many of her patients.

For puppies and small or toy breeds, Dr. Dodd recommends adding a half-teaspoon Kyolic liquid three times a day for one week, followed by a half-teaspoon once a day. For adult dogs, the dose is one teaspoon three times a day for one week and one teaspoon per day after that, and for large breeds, one tablespoon three times a day for one week and one tablespoon per day for maintenance.

Any of these nutritional support products can be used in any combination by puppies and dogs with multiple problems, helping today’s debilitated rescue dog shine in perfect health for years to come.