Caper was a Spuds McKenzie-style Bull Terrier mix – white with a rakish black eye. She spent the first 18 months of her life running free in the small California coastal community of Bolinas, where resident dog owners eschewed leashes and threw bottles at trucks driven by animal services officers. As happens all too often with dogs who are given too much freedom, the energetic terrier got into trouble – she nipped a small child who tried to play with her on the beach. I adopted Caper upon her release from bite quarantine at the Marin Humane Society more than 20 years ago, and immediately enrolled her in an obedience class.

Caper excelled in class despite the fact that in those days I was still using compulsion-based methods. It seemed to me at the time that the vigorous yanks that I applied to her leash and choke collar didn’t dampen her enthusiasm for training in the slightest. When we ventured into the obedience competition ring she was always in the ribbons.

Her recall in the ring was superb. On the judge’s instructions, I would leave her in a sit-stay, march to the opposite side of the ring, wait for the judge’s signal, and then issue the clarion call, “Caper, come!”

Caper would rocket across the ring and slam her compact, muscled body into an unerringly straight sit at my feet, gazing into my eyes with adoration and anticipation. My next command invariably sent her into another faultlessly straight sit at heel position to complete the exercise – a picture-perfect show-ring recall.

Outside of the ring, however, the picture wasn’t quite so perfect. If Caper was within 40 to 50 feet of me, my “Caper, come!” command worked – a good 98 percent of the time. If she was farther away, however, the word “come” more often than not served to lend wings to her heels as she fled directly away from me on some compelling Bull Terrier mission. Was it a coincidence that our show-ring recall was also performed at a distance of about 40 to 50 feet? I doubt it.

I stumbled over a solution to Caper’s recall problem totally by accident. I acquired an Australian Kelpie – a breed with intensely strong herding instincts. Whenever Keli the Kelpie heard the note of hysteria in my “Come!” command that meant Caper was running off again, she would charge after the errant terrier on her lightning fast Kelpie legs and forcefully herd her back to me. Problem solved.

This, however, is not the solution I would use now, and it’s certainly not the one that I can offer my clients today for teaching their dogs a reliable “Come.”

Still a four-letter word

“Come” is perhaps the most important behavior we can teach our dogs – and the most difficult one. The average dog owner spends far too little time teaching “Come” as an exercise. We tend to use it mainly in real life, in situations when we really need the dog to respond, and then we get upset if he doesn’t. When does the average dog owner usually call her dog? When the dog is doing something he’s not supposed to do – something that is infinitely more fun and rewarding than returning to his human.

“Let me see,” ponders Rover for a tenth of a gigasecond. “Chase the deer or go back to my person, who sounds like she’s mad at me, and who is probably going to put me in the car and take me home? Roll in the dead squirrel or go back to my person? Eat horse poop or go back to my person?” The person loses every time! To make matters worse, she starts to use an angry tone of voice when she calls Rover, and “Come” quickly becomes a four-letter word. Rover learns, like Caper did, to run away from people when they use the bad “Come” word.

There is a much better way. If we condition Rover respond to a “Come” cue that means “wonderful things are happening here!,” even if the “wonderful thing” isn’t really as good as eating horse poop, prior positive conditioning can triumph over the allure of tasty horse poop, chasing deer, and perfuming oneself with dead squirrels.

We want our dogs to think that “Come!” is the best thing in the whole world. We do this by teaching a positive association with the come cue, and by making sure that the consequences of coming are ALWAYS positive. We NEVER punish Rover for coming to us, and we never resort to intimidation and threats to make Rover come to us.

Punishment is anything that Rover doesn’t like. This means that if Rover doesn’t like having his nails trimmed, don’t call him to you, evil nail clippers in hand, then nab him for a manicure when he arrives. If you do, you’ve punished him for coming, and he will be a bit more leery about coming to you the next time he is called. If Rover stays in the back yard while you are gone all day at work, but he’d really rather be in the house, calling him to you and tossing him in the back yard just before you leave for work is punishment.

Of course, you do need to trim his nails, and perhaps you do need to put him in the yard when you leave, so what are you supposed to do? You have several choices. You can call him to you, do something very fun for 10 to 15 minutes, and then say, “Oh, by the way, as long as you’re here, let’s trim your nails.” This way, the “bad thing” is far enough removed from being called that he won’t make the association between the two. If you do this too often, however, there is a danger that he may start to realize that bad things often follow being called, especially in a certain context, such as your preparations to leave for work.

You can also walk up to Rover, wherever he happens to be, feed him a treat, take hold of his collar and proceed to trim nails – although if you do this too often with negative things he will learn to move away when you approach. The most elegant solution is to convince him that nail trimming and going in the back yard are wonderful things, so that calling him to you to do those things is a good thing, not a bad thing. If you make it a point to go out in the yard and play with Rover before you leave, he will think going in the yard is wonderful. If you gradually desensitize Rover to the nail clippers with yummy treats, he may never love having his nails trimmed, but at least it will seem more good to him than bad. Meanwhile, you need to teach Rover to come on cue as a fun game, totally separate from doing negative things. Here’s how:

Short-distance, low-distraction come

Start with short-distance recalls in a low-distraction environment – a quiet room in the house – where you are by far the most exciting thing happening. Have a handful of over-the-top tasty treats that Rover doesn’t get during regular training sessions, such as squeeze cheese, string cheese, bits of ham or roast beef, baby food, or anything else that will really make Rover’s eyes light up. With Rover just a few feet away from you, say his name in a cheerful tone of voice. When he looks at you in response to his name, run backwards several steps and say the word “Come!” – also in a very happy voice. The message implied by your tone should be, “Hey, we’re having a party over here, and you’re invited!” Be sure to run backwards. Running triggers a dog’s chase instincts and increases your attraction potential to Rover severalfold over standing boringly still.

As soon as Rover starts moving toward you, use a reward marker that has already been paired with food, such as the Click! of a clicker, or the word “Yes!” You are marking the behavior of coming toward you, and letting Rover know that moving toward you has earned him a reward. This will also enhance the “Come,” since Rover is likely to hurry faster toward you to get his treat after he hears the clicker.

As Rover approaches, stop moving, and tell him what a wonderful dog he is. If he sits easily for you, lift the treat as he arrives at your feet. (Do not ask him to sit.) If he sits, great! Feed him the treat and tell him he’s fantastic. If not, go ahead and give him the treat anyway, and tell him he’s wonderful. It’s nice if our dogs sit when they come to us. It parks them briefly, so we can restrain them if necessary, and it is also much better than coming to us and jumping up. If sitting is a challenge for Rover, however, and we get into a sit-struggle when he comes, then we are punishing him for coming, and come is no longer positive and fun. If Rover doesn’t sit easily, give him the treat just for coming, and make a mental note to work on sit as a separate exercise.

Medium to long distance, low-distraction come

When Rover is happily playing the short-distance come game with you, gradually start increasing the distance between you and Rover when you call him. Remember to mark the desired behavior – coming toward you – with a Click! or “Yes!” as he is coming toward you, to encourage him to keep coming for his treat reward. Be sure to use lots of enthusiastic praise as well, to keep the party attitude.

The “round-robin” come

Now that Rover thinks that “Come” is a fun thing, you can include friends and family in the training game. Have several people in the room, each with a clicker and a handful of equally tasty treats. Take turns calling Rover, in no particular order. Each person Clicks! and treats Rover as he arrives, then another person calls him.

Note: If one person in a group calls Rover, the other people must ignore him if he comes to them instead. No eye contact, no petting, no treats, no talking to him. He’ll quickly learn that only the person who called him has any rewards.

Adding mild distractions

Here’s where most people start to lose the training game. Rover comes beautifully in the house, therefore, he knows what “Come” means and he is trained to come when called – right? Wrong! He is beautifully trained to come when he is called, in the house, if there is nothing more interesting around. Now we have to teach him to come in other places, even when there’s other good stuff happening.

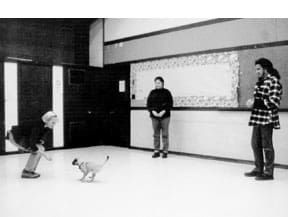

For this exercise, put Rover’s leash on. You are not going to jerk him with it, you are just going to use it to prevent him from being rewarded for going somewhere else when you call him. Start small. Have a friend moving around in the room while you practice short-distance recalls. (Each time you change the rules of the game, go back to short recalls and gradually increase the distance.) Instruct your friend to ignore your dog if he approaches her instead of coming to you. When Rover responds to your “Come” cue even with mild distractions, drop his leash and start increasing the distance, until he will romp to you across the room, even with another person, a ball, a cat, or a child in his path. When he will do this, you’re ready to take the show on the road.

Adding major distractions

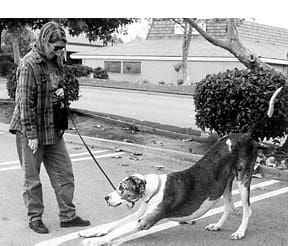

Until now, we’ve been working indoors. Outdoors is a whole new ballgame. There are all kinds of wonderfully enticing things for Rover to pursue outdoors – great things to smell, eat, see, chase, roll in – you are going to have to work very hard to make yourself more interesting than the nearest dead squirrel. Arm yourself with your tastiest treats, and go back to square one – short distance recalls on-leash. If you’ve done your homework well in less distracting environments, Rover will catch on quickly, and your progression to longer distance and Round-Robin recalls will happen much faster than your initial training. As you increase the distance, use a long-line to prevent Rover from getting rewarded by getting to run off and enjoy an unanticipated distraction.

Advanced recall challenges: The “Premack Principle”

The greatest challenge of “coming-when-called” is the reality that there will always be something out there that is more enticing than whatever we can offer Rover. In order to overcome this challenge, we use the Premack Principle, which teaches Rover that in order to get the wonderful thing at location “B,” he has to come to us first at location “A”. That is, if he wants to chase the squirrel up a tree, he comes to us first when we call him, then we let him go chase the squirrel.

You can teach your dog the Premack concept through controlled exercises. Start by having a friend stand with Rover, 20 feet away from you. The friend has a handful of yummy treats, and lets Rover sniff and lick her hands, but does not give him any treats. Call Rover to you. It may take a while for him to decide that he’s not going to get any treats from your friend. That’s okay – just keep calling him in your happiest party voice. If necessary, squeak a squeaky toy, jump up and down – do whatever you need to do to get Rover interested in you. When he starts to come to you, Click!, and feed him treats when he arrives. Your friend should follow behind him, and give him her treats after he eats yours. He gets a double reward for coming to you – your treats and her treats. When he will do this exercise easily, he’s ready for the advanced Premack challenge.

Empty a can of canned food (or something equally smelly and attractive that is not his normal food), and set it off to the side. Have your friend stand behind the plate with a bowl that she can use to cover the plate. Show Rover the plate of cat food, then put him on a sit-stay about 20 feet from the plate. Walk 20 feet away from Rover in a different direction so that you, the plate (and your friend) and Rover form the points of an equilateral triangle. Now call Rover. If he comes to you, great! Good boy, Rover! Mark that behavior (Click! or “Yes!”), give him a treat, and then run with him over to the bowl of special food and let him have a healthy mouthful.

But if he heads for the plate first, have your friend quickly cover the plate with the bowl to prevent him from eating the food. Keep calling him until he gives up on the cat food and comes to you. Good boy, Rover! Click!, treat, and run back with him to the plate for a mouthful of food. Keep practicing until he figures out that the onlyway to get the cat food is to come to you first. Now you and Rover are starting to achieve a really reliable recall!

A few final recall tips

If you are working with a dog like Caper, who already has a negative association with the word “Come,” you might want to switch to a new recall word. Some dog owners use “Close” or “Here.” You can use any word you want – it doesn’t have any meaning for Rover until we associate it with the “come” behavior. Just be sure to keep the new word positive, or you’ll be looking for yet another one.

Make a real commitment to teaching your dog a positive “Come.” It doesn’t happen overnight. In fact, it can take two or three years to teach Rover to come reliably in the face of his most enticing distractions – if you work at it; it doesn’t happen all by itself.

Meanwhile, don’t put your dog in a situation where his lack of reliable recall can endanger his life. That is, don’t take him off leash in places where he can run away and get into trouble, like I foolishly did with Caper. I was extremely lucky that Caper never got into serious trouble when she ran off, and I was fortunate to find a serendipitous solution to Caper’s recall challenge.

Caper has long since died – of old age, not from a failed recall, thank goodness. I would love to have her back again, to show her how much fun “coming when called” can be, but of course, I can’t. I’ll just have to make it up to her through all of my current and future dogs, through all of my clients’ dogs who come to me for training, and through you, the WDJ reader who can teach your dogs positive, reliable recalls. Let the recall games begin.