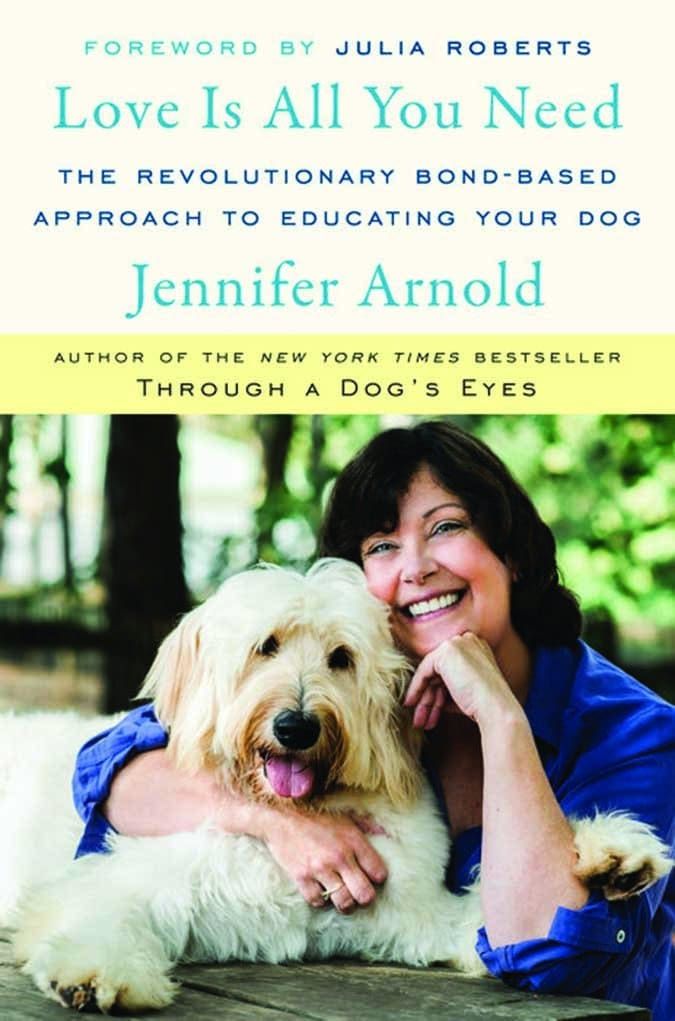

Some canine educators are taking the idea of “choice” to a new level. Jennifer Arnold is the founder of Canine Assistants, a service-dog school in Milton, Georgia, and the creator of the “Bond-Based Choice Teaching” approach to interspecies relationships. This program focuses on developing relationship and communication between human and canine partners rather than teaching a list of tasks. Her just-released book, Love is All You Need: The Revolutionary Bond-Based Approach to Educating Your Dog, describes her journey through (and disappointments with) positive-reinforcement-based training, and describes her bond-based training system.

Love is All You Need presents the history of and details about the program Arnold uses to successfully develop working assistance dogs at her Canine Assistants facility in Milton, Georgia. She reports an exponential increase in the number of successful canine graduates from her program since the implementation of Bond-Based Choice Teaching.

I love the concept of bond-based teaching. Rather than starting by learning to respond to traditional cues (such as “Sit,” “Down,” etc.), Arnold’s puppies – future assistance dogs – begin by learning concepts. She associates vocabulary words with activities, objects, people, and places rather than the performance of specific behaviors, and introduces games that encourage bonding, trust, and self-reliance. Sounds good!

Learn more in our article, Training a Dog to Make Choices.

Still, some of her suggestions fly in the face of some common practices. Her answer to jumping up? She says, “It simply isn’t fair to punish your dog who is asking for attention by removing your attention.” She maintains that a dog who jumps up in order to connect with a person should not be ignored. Rather, she suggests feeding the need by using both hands to massage him while giving him your compete attention. She calls this “Two Hands, All In” and says that in every case where a dog’s problem behavior is the result of an emotional need, it is our obligation to fill that need.

There is a lot of food for thought in this book. There is much that I find intriguing and would like to pursue, and also much that I disagree with. Arnold criticizes modern trainers for their focus on operant conditioning without acknowledging the great interest force-free trainers have already demonstrated in regard to the concepts of empowerment, choice, and cognition in their training programs. She insists that dogs really are “eager to please” their humans – an idea I have long argued against. She hasn’t convinced me on that topic, but I do wholeheartedly agree with her that we need to improve our relationships with our dogs by working with their cognitive abilities and giving them more opportunities for choice and empowerment.

Arnold has plowed fertile ground here. I look forward to seeing what grows from it. I hope it will be generation of dogs who experience far less stress and anxiety in their lives.