What do you want, you crazy dog?” Jennifer Wade said with a smile to her diabetic alert dog, Raven. Wade, 30, had just eaten a meal at an office luncheon, so she knew her blood glucose level (blood sugar) had to be okay. But Raven persisted, tugging her, and getting in her face. She guessed that the food-crazy dog just wanted an apple from the party, and her co-workers encouraged her to allow the persistent black Labrador Retriever to have a bite. Wade relented, but the chow hound declined the offer. In a hurry to get back to work, Wade exclaimed, “Now what?! You’re not going to eat? What is wrong with you?”

www.leahvalentine.comService Dog of Virginia

Raven tugged at Wade’s wrist strap, jumped up on her, and eventually sat and stared at her with big, sad, brown puppy eyes and began whining. “Okay, if it will make you happy, I’ll check my blood sugar, you silly dog.” Sure enough, her blood sugar level was low. She gave Raven the signal to let him know he was correct, and he lit up, dancing around with excitement . . . and ate the apple.

I know my blood sugar is dropping when I start to feel cranky or fatigued. Fortunately, I can ride out my discomfort until I have a moment to grab a snack. But imagine you have no indication that your blood sugar is dropping. For diabetics who have “hypoglycemia unawareness” – a condition in which a person with Type I diabetes doesn’t experience the usual warning symptoms of hypoglycemia – the consequences of not acting immediately on a fast-dropping blood sugar level can be fatal.

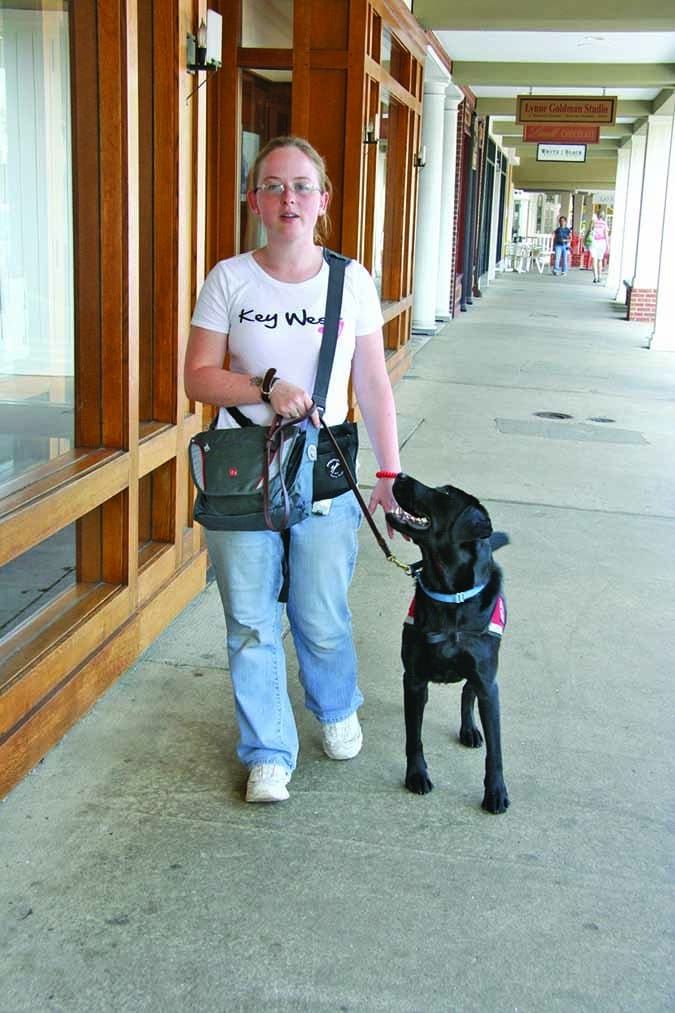

Cue Raven, who entered Jennifer Wade’s life in July 2011, nine years after her diagnosis with diabetes – after struggling for nine long years to maintain appropriate blood sugar levels. A Type I diabetic, Wade found herself falling asleep at night, but not waking in the morning due to precipitously low blood sugar levels. As a single mother of a five-year-old boy, Wade (who has since married), was distressed that the burden to be sure that Mom was okay – including summoning 911 emergency assistance – might fall to her young son. Diagnosed as having hypoglycemic unawareness, she stopped going out in public unless accompanied by another adult.

A Dog’s Nose Knows

Trained by Service Dogs of Virginia (SDV), a 501(c)(3) non-profit service dog organization, Raven signals Wade when her blood sugar is on its way down or low, presumably based on a scent that diabetics emit when blood sugar levels begin to drop. Raven’s alert is to tug on an elastic band that Wade wears on her left wrist.

Peggy Law, founder and director of SDV, says that while diabetic alert dog programs are in their infancy, dogs have always smelled low blood sugar. “We don’t teach them to smell anything – we teach them to tell us when they smell it. The dogs just didn’t know we cared!”

Law trains and places diabetic alert dogs only for clients diagnosed with hypoglycemic unawareness – folks who have a greater than usual challenge in managing this tricky disease. She explains that dogs seem to notice when a human’s blood sugar drops rapidly, “even if the client’s level isn’t yet low.” When the dog alerts repeatedly as the level continues to drop, the client can immediately take action (eat, drink) to prevent a drop to an unsafe range.

When the client’s blood sugar decline is very gradual, dogs tend not to notice until the level is low. Given this, says Law, SDV’s goal is to train the dogs to alert when the client’s blood glucose level is at 70 mg/dl or below, but before the point of no return when the person can’t think clearly enough to eat or drink on her own. “We want the dog to alert while the person is still functioning so she can fix the situation.”

Before Raven was placed with her, Wade had been employing a risky strategy in managing her blood sugar levels. “When I started having episodes, I was afraid to keep my sugar at normal levels; I was so afraid that’d I’d pass out [if her blood sugar got low], so I kept it high,” Wade describes. While the outcome of high blood sugar in the short term is not as deadly as a precipitously low level, consistently abnormally high blood sugar causes long term damage that can lead to outcomes such as amputations and blindness. But now that Wade has an emergency backup indicator in Raven, she feels safer with lower average blood sugar levels than before. “Having Raven and knowing that he does his job well gives me confidence to keep my sugars where they should be. Since getting him, my average blood sugar (A1C) has been the lowest [most normal] that it’s ever been.”

The Magic of Positive Training

When Wade first brought Raven home, the dog was legitimately alerting Wade four to five times a week. Now, with her blood sugar under better control, she’s down to two to three alerts per week.

When Raven alerts, she’ll tell him, “OK, let me check my sugar.” The Lab knows the routine: he lies down, stares at her, and waits. If she’s low or on a downward trend, she praises him with a “Good dog! Let’s get a treat!” while she gets him a treat and grabs some juice for herself. His response? “He thinks he’s the cat’s pajamas! He’s all excited and thinks he’s the best dog in the whole wide world,” Wade laughs.

A diabetic alert dog’s road to reach that point is long. Raven came to SDV from a breeder at eight weeks of age and lived with a volunteer puppy raiser for his first year of life. During that year, SDV’s goals are to ensure the dog is comfortable in public, and to work on basic good manners behaviors, in order to establish groundwork for advanced behaviors. Then the dogs come back to live with an SDV trainer to embark upon advanced training for another year.

SDV utilizes positive training methods and clicker trains most behaviors, including alert training. Law and Wade appreciate the engagement, motivation, focus, and “think on your feet” attitude this method of training cultivates in dogs – an attitude that might mean the difference between life and death.

For example, one day Raven found Wade on the floor beside her bed, “sleeping.” Raven was in SDV’s second class of diabetic alert dogs and had not been formally trained to get help if Wade didn’t respond to his alerts. (This behavior has since been included in the program.) Wade vaguely recalls the dog repeatedly tugging on her wrist strap – and pushing him away. Frustrated and determined, the dog left the room and alerted Wade’s husband, who called paramedics.

SDV takes a slow approach to alert training that calls upon the dog’s strong clicker-based foundation. Alert training starts by “charging” the scent, rewarding the dog whenever the scent is presented to him in order to make it significant to him, and then teaching him to perform a specific behavior when the scent is presented. Eventually, he learns he will be rewarded for performing that behavior (now called an alert behavior) whenever he detects the scent.

The tasks increase in difficulty, with the scent being presented randomly, in all sorts of different situations and environments. Through months and months of repetition, working through false alerts and a gradual increase in the difficulty of the “game,” the dogs understand that being right leads to a party: big rewards (SDV uses food rewards) and lots of praise.

Relationship is Key to Training Dogs

SDV spends close to two weeks working with clients to “transfer” the dogs to their people. Law describes it as learning to dance with a partner. “The dog knows how to do the dance, but they can’t lead. The person has to learn to lead the dance, but they have to learn the steps first.” The client gets instruction on lots of dog training basics, and, at the same time, the relationship starts to build. “The dog is hanging out with them during training, and therefore has the opportunity to alert. The first few times it happens, the client is shocked,” Law explains.

Part of client orientation includes imparting an understanding that the dog is not an alert machine. Law says, “When you have a dog with you at work, the grocery store, and everywhere you go, you develop a deep knowledge of one another if you listen to and observe your dog. That can only help strengthen the dog’s persistence and determination when needed. The bond is a two way street: many people want a dog just to work, but forget that the dog has to be provided for physically and emotionally.”

And she stresses that, “Any time you’re training service dogs, it’s not just about the task (the alert); it’s about the dogs being very comfortable in public. There’s no way they can do this job if they’re not comfortable being out there. You also can’t expect them to work 24 hours a day. They’ve got to be able to have some down time.”

Positive Training Works

We still don’t know exactly what chemicals these dogs detect in order to be able to accurately alert to a low blood sugar level. Despite the fact that there is proof in her numbers, validated by her endocrinologist (who is a big supporter of diabetic alert dogs), Wade has been confronted by skeptics who assert that the dog is just guessing and happens, on occasion, to be right. Wade’s response? “My sugars have been the best they have ever been, my numbers reflect that, and I’m more confident than ever before. If it’s all in my head, so be it, because not only are my levels a lot better, my life is a lot better, too!”

SERVICE DOGS OF VIRGINIA – Charlottesville, VA.

Lisa Rodier lives in Georgia with her husband and Atle the Bouvier, and volunteers with the American Bouvier Rescue League.