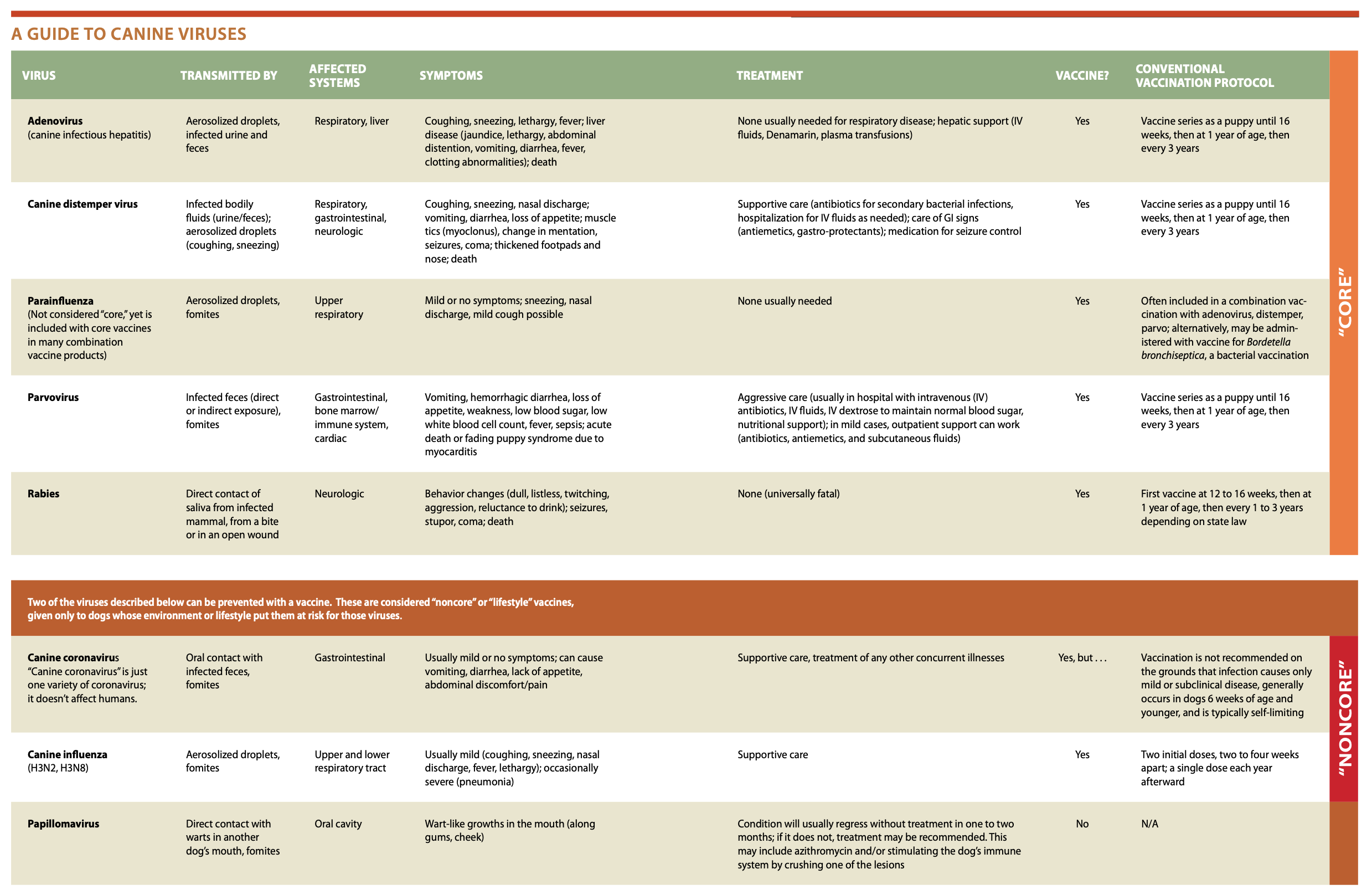

Canine viruses have existed for thousands of years. Today we have tools to combat and prevent many of the diseases they cause. But despite this, viruses linger and mutate in wildlife and domestic dog reservoirs, so it’s important to understand how they work and how to prevent them.

Viruses are not actually living organisms. Containing only one piece of genetic information – either DNA or RNA – they require a host cell to survive and reproduce.

Once in the body, the virus hijacks normal cells and uses them to reproduce. Eventually, the host cells become overwhelmed with new particles and explode, releasing more virus into the bloodstream. The cycle continues. Every system in the body, from the skin to the brain, can be affected by viruses.

Viruses are spread by a variety of mechanisms. In dogs, these include aerosolized droplets from barking, coughing, and sneezing; saliva transmission via bite wounds; and the fecal-oral route (this occurs when a dog eats or licks the feces of an infected host). Urine, ocular, and nasal discharge can also lead to exposure in some cases. Fomites (inanimate surfaces such as bowls, beds, crates, kennel walls and doors, leashes, and grooming equipment) also play an important role in transmission of disease.

Once exposed to a virus, it can take anywhere from a day to weeks for symptoms to manifest, depending on the particular virus.

PREVENTION

There are many ways to prevent infection. Keeping your dog healthy and fit with regular exercise and an excellent diet is the best way to promote a robust immune system. It’s also important to keep up with routine treatments that prevent infections by parasites, such as gastrointestinal worms, heartworms, fleas, and ticks, since the burden of parasites can sap the dog’s health and vitality.

Avoiding social situations where dogs with illness may be present is another good idea. When considering boarding and daycare facilities, choose one with strict sanitation policies and vaccine requirements. Since many canine viruses can be transmitted via infected bodily fluids such as feces and urine, as well as on fomites like water and food bowls, cleanliness is important in limiting spread of disease.

It’s also critical to keep your dog home if she manifests any signs of illness.

Vaccines are a safe and effective way to protect your dog and are available for almost all of the major canine diseases caused by viruses. Vaccinations are not “one size fits all,” and you should work closely with your veterinarian to determine which vaccines are most needed for your dog.

All puppies should receive a series of vaccines until they are 16 weeks of age. Vaccines are generally given again a year later, and, according to the the most commonly accepted canine vaccination guidelines, every three years after that.

Some dogs should not be vaccinated on this schedule. This includes dogs with immune-mediated diseases, like hemolytic anemia and dogs with a history of severe vaccine reactions. Some vaccines may be discontinued for senior dogs after a certain age, depending on lifestyle. Titers are another method that has been utilized to determine when vaccination is necessary. (See “Taking the Titer Test,” WDJ June 2014.)

WHY RISK IT?

Prognosis and recovery from a virus is highly dependent on the causes. The rabies virus, for instance, is universally fatal. Other viruses, like parainfluenza (a mild, often asymptomatic upper respiratory tract infection), may never cause any illness.

As always, an ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure with regard to viruses.

After nine years in emergency medicine, Catherine Ashe, DVM, now works as a relief veterinarian in Asheville, NC.

Hi there my dog loves to go to the beach !!